Second advance estimates (AE) of national income of 2020–21 broadly endorses the GDP (gross domestic product) optimism narrated in the first advance estimates. Real GDP at constant (2011–12) prices has been projected to be to the tune of INR 134.09 lakh crore. Compared to the 2019–20 first revised estimate (RE) of GDP at INR 145.69 lakh crore, the growth rate is estimated to be -8.0 percent in 2020–21. In 2019–20, the real GDP growth rate was 4.0 percent.

This signifies a possible economic recovery in coming months. However, the first AE had projected a growth rate of -7.7 percent in 2020–21 real GDP. So, there is a 0.3 percent downward revision of real GDP growth in the second AE. There is an upward revision in GDP at current prices in second AE at -3.8 percent. In first AE, the current GDP growth rate was projected to be -4.2 percent.

If GDP at current prices grows more than the GDP at constant prices, then that points towards a presence of an upward inflationary pressure.

This may be a cause for worry in the near future. If GDP at current prices grows more than the GDP at constant prices, then that points towards a presence of an upward inflationary pressure. So, maintaining a tolerable price level remains an immediate challenge.

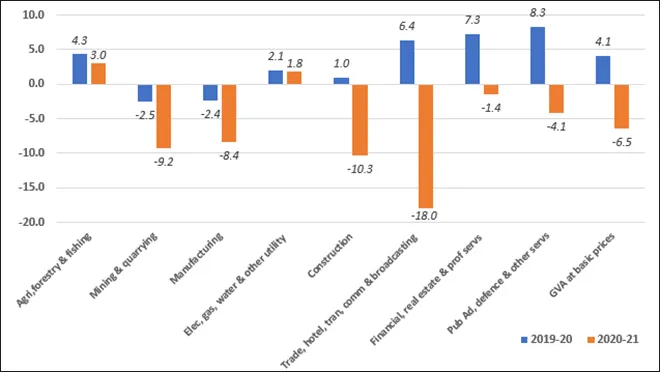

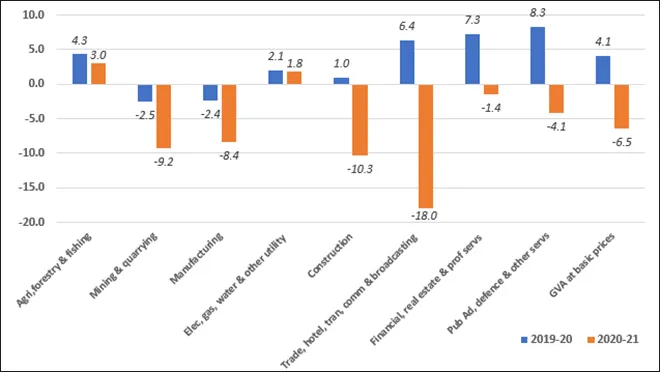

FIGURE 1: Sectoral growth rates of GVA at basic prices (2011-12 series) in 2019-20 and 2020-21 (in %)

Data source: Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI)

Data source: Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI)

* Year-on-year growth rates are calculated using 2018-19 (2nd RE), 2019-20 (1st RE) and 2020-21 (2nd AE)

* RE = Revised estimates, AE = Advanced estimates

A comparison of growth rates of GVA (gross value added) in principal sectors of the economy in 2019–20 and 2020–21 (Figure 1) reveals a fact that is not getting adequately highlighted in popular discussion on GDP and economic revival. Sectors like mining and quarrying, and manufacturing had undergone negative growth even in 2019–20. Growths in construction and electricity, gas, water supply, and other utility services had also been small and marginal in the same year.

So, these sectors were already at a lower base in 2019–20 compared to 2018–19 output. Therefore, growth or contraction in these sectors in 2020–21 need to be analysed after taking these lower base values in consideration.

Overall GVA growth in 2019–20 (at 4.1 percent) was mainly driven by three principal private and public services sectors — (a) trade, hotels, transport, communication, and services related to broadcasting, (b) financial, real estate and professional services, and (c) public administration, defence, and other services.

If more goods are produced in the brick and mortar economy then there will be subsequent demand for all kinds of services in the economy. The converse is also true.

This implies that the brick and mortar economy — particularly the industry and manufacturing — contracted before the pandemic arrived as an economic shock. The services sectors, including the financial sector, compensated for that deficiency and propelled the economy upwards in 2019–20. However, services sectors have backward linkages with the industry, manufacturing, and construction sectors. In simple words, if more goods are produced in the brick and mortar economy then there will be subsequent demand for all kinds of services in the economy. The converse is also true. If there is a slowdown or stagnation in the industry, it is bound to catch up with the services sectors — generally with a time lag.

Financial services have been less affected during the pandemic in 2020–21 because banking and other allied serviced were operational during lockdown. That is why the contraction in this sector is relatively less at -1.4 percent. But it will be imprudent to assume that financial services will keep on thriving even if the industries are not keeping pace.

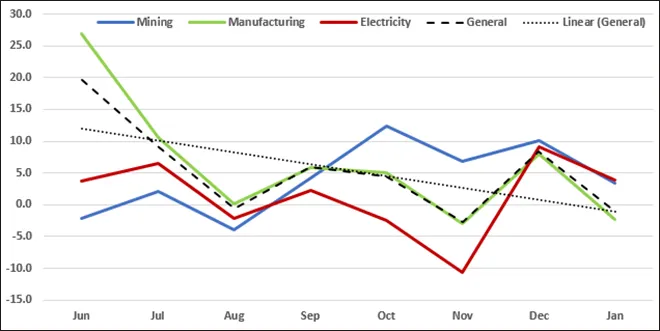

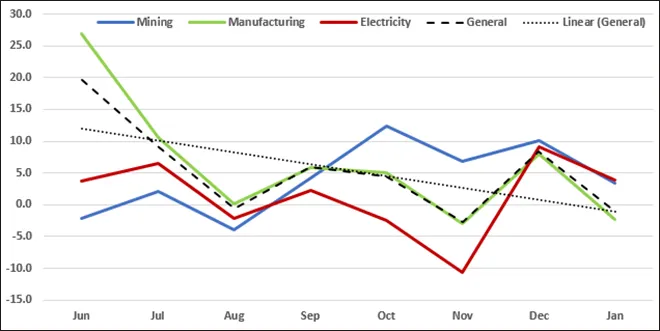

Quick estimates of Index of Industrial Production (IIP) for the month of January 2021, to a great extent, demonstrate this lack of dynamism in industries.

FIGURE 2: Month-on-month growth trends in sectoral IIP during June2020-January2021 (in %)

Data source: Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI)

Data source: Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI)

* Figures for January 2021 are quick estimates

Month-on-month growth trends in sectoral IIP (Figure 2) show some amount of revival in the months of October and December. These two months coincide with the festive seasons, and some amount of pent-up demand after the lockdown also played its role in these spurts.

After the lockdown was lifted in June, the immediate growth rates naturally would be much higher than usual and, therefore, subsequent easing of rates would tend to create a downward slope.

However, immediately after these spurts, IIP growth has slumped in the next month, across all sectors. This has now happened twice — in November 2020 and January 2021. The pandemic maintained its volatile nature in the economic activity centres of the country — number of infections getting subdued in one phase and gradually growing back in the next. This has definitely hindered economic performance. But along with the pandemic-related factors, this constant bouncing at a lower base probably needs to be contextualised with the industrial deceleration in 2019–20 before the pandemic — as explained earlier.

Month-on-month general IIP growth also shows a downward sloping linear trendline. Part of this downward slope is comprehensible. After the lockdown was lifted in June, the immediate growth rates naturally would be much higher than usual and, therefore, subsequent easing of rates would tend to create a downward slope. But what happened in October and following three months indicates towards a probable pattern of stagnation in industrial production. This may not be good news for recovery.

Despite the GDP optimism, the Indian economy cannot attain normalcy in the long run without addressing these glitches in its industrial sectors, particularly in manufacturing.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Data source: Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (

Data source: Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation ( Data source: Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (

Data source: Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation ( PREV

PREV