-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

IMF’s growth projections for FY2017 seem a little optimistic — economic growth will be lower than 7.2%. Likewise, its growth projections for FY2018 seem a little pessimistic — economic growth will be higher than 7.7%.

Image Source: PTI

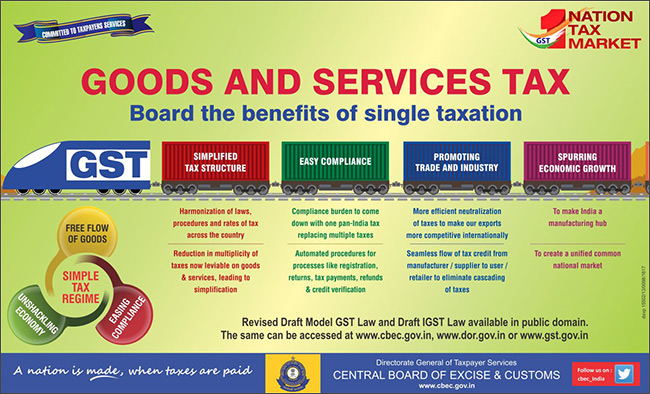

Officials interacting with traders as they spread awareness regarding GST

In its latest World Economic Outlook Update, released on 24 July, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) may not have factored in India’s introduction of the goods and services tax (GST) in its growth projections. While data is yet to flow in, anecdotal evidence suggests a hold back of goods from retail outlets. From almonds to pens to books, there is a minor pause in some sectors and downstream consumer-facing businesses. We are a week away from the first month of the GST implementation and the economic griping and political whining aside, there is a real and present danger to growth. Note, these are mere anecdotes in the longer story of GST and to get a definitive view, we need patience and wait for data.

On the empirical side, what we have is the following. At 7.2% in FY2017 and 7.7% for FY2018, India remains the world’s fastest-growing significant economy, the IMF Outlook states. To get a sense of perspective, these numbers beat the world’s second-fastest growing economy and India’s economic rival China’s growth rate by 50 basis points and 130 basis points in the two years. The world output is slated to rise by 3.5% and 3.6%, emerging market and developing economies are projected to grow by 4.6% and 4.8%, with the fastest-growing region, emerging and developing Asia, expected to lead at 6.5% for both the years.

|

2017 |

2018 |

|

| India |

7.2 |

7.7 |

| China |

6.7 |

6.4 |

| World Output |

3.5 |

3.6 |

| Spain |

3.1 |

2.4 |

| Canada |

2.5 |

1.9 |

| US |

2.1 |

2.1 |

| Mexico |

1.9 |

2.0 |

| Germany |

1.8 |

1.6 |

| UK |

1.7 |

1.5 |

| France |

1.5 |

1.7 |

| Russia |

1.4 |

1.4 |

| Japan |

1.3 |

0.6 |

| Italy |

1.3 |

1.0 |

| South Africa |

1.0 |

1.2 |

| Brazil |

0.3 |

1.3 |

As if the GDP hit by demonetisation were not enough (more on that below), the government has gone ahead with the implementation of GST, and introduced another major disruption that makes the tax system across India smoother and more predictable, the velocity of transactions and delivery of goods faster, and through its ingenious incentive structure pulls more businesses into the indirect taxes network.

In the age of constant and almost predictable disruption, the fact that India continues to grow shows the tenacity of its economy and the courage of its leadership to take policy risks of breaking down old and archaic structures and replacing them for a 21st century India.

Read also | GST will curb evasion of both, indirect and direct taxes

The transition to this more efficient tax system was supposed to ease doing business for those within the tax net — a single tax for a single product across the country, no barriers to inter-state transporters, an incentive system that delivered tax credits down the line from the manufacturer to the retailer, and an electronic backend infrastructure in the form of the Goods and Services Tax Network (GSTN) to support the new indirect taxes system. For those outside the tax network, the GST system was supposed to force them in — most of the cries we hear on streets belong to these evaders and the political system that uses noise and demonstrations to gather power. All of these were expected and the drama is playing to the script. Going forward, the inevitability of the GST system will finally dawn on entrepreneurs and they will embrace it. Crooks, whose business model was tax evasion, will be ejected out of the system; some will find new ways to remain crooked. We don’t need to shed any tears for them.

Where we need to be careful is in our projections. Of course, GDP growth will slow down — every economist knows it, the government is aware of it — as economic actors understand and experience the new system that needs time to stabilise. Arguments that the GST should have been implemented after some time are illiterate — the same arguments would have been heard three months, six months, 12 months from now…we would be hearing them a decade later. The other noise, about reducing tax rates on this commodity or that service, will continue too, intensely in the first quarter and taper down by the second quarter of GST implementation.

The real problems of the GST system are not on rates or the timing of its implementation. It is on and around the new compliance system that Indian economic agents are not used to.

Add the good old method of tax policy — to treat entrepreneurs as criminals by the tax bureaucracy — and what you have is needless panic in the economy. Better to stay out than get enmeshed in this new system, goes the argument. The complexity of compliance is such that it would be impossible not to make an error. On its part, the government is assuaging these fears: Commerce Minister Nirmala Sitharaman has assured entrepreneurs that there would be no penalties for wrong entries in the first two months of GST implementation. That said, once the cobwebs of compliance get cleared up, the increase in the velocity of transactions, the efficiency of tax collection, a shift of the informal economy to the formal in the medium term and the benefits to doing business, will come together in a virtuous cycle and power growth.

Here, we need to take lessons from the other disruption: demonetisation. As an experiment to flush out black money, it may not have delivered the several and serial results Prime Minister Narendra Modi alerted us to in his 8 November 2016 address to the nation, and his ministers and officials subsequently added to — from corruption and black money to terror funding, counterfeit notes and fall in real estate prices, demonetisation was supposed to be the silver bullet to fix all of India’s economic and moral ills. Barring a fall in real estate prices, none of that has happened so far. What we do see are silver linings in the form of nuggets of data are now coming out that when aggregated over the next 12 months or so would translate into increased number of taxpayers and some expropriation of taxes evaded. Those who deposited old notes beyond a certain amount, for instance, would be questioned and if the money is found to be out of synch with their known sources of income, the would be penalised. Demonetisation has increased the risk to dealing with cash.

Read also | GST is a marathon, not a 100-metre dash

The only big macroeconomic result that demonetisation has delivered so far is a short-term blip in economic growth: at 6.1%, the slowdown in India’s GDP growth for the January to March 2017 quarter, the first full quarter after demonetisation, was the lowest in two years, down from 7.4% in the previous quarter and 7.6% in the same quarter of the previous year. That quarter also saw India relinquish its position of being the world’s fastest-growing large economy to China, which grew by 6.9% in the same period. India closing FY2017 with a growth rate of 7.1% was surprisingly higher than anticipated. These, IMF notes, were “due to strong government spending and data revisions that show stronger momentum in the first part of the year”. Now, the negative impact of demonetisation, “seems to be fading”, the multilateral bank stated in its 8 July note prepared for G20 leaders, while keeping India’s growth projections stable.

The impact of GST on economic growth will follow the same path as demonetisation did: short-term blip, medium-term stabilisation and long-term catalyst to economic growth. That’s why, IMF’s growth projections for FY2017 seem a little optimistic — economic growth will be lower than 7.2%. Likewise, its growth projections for FY2018 seem a little pessimistic — economic growth will be higher than 7.7%.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Gautam Chikermane is Vice President at Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi. His areas of research are grand strategy, economics, and foreign policy. He speaks to ...

Read More +