-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The Ukraine Crisis has strengthened the EU from within and forced it to undertake measures to bolster EU institutions

President Biden’s speech in Warsaw and President Putin’s state of the nation address, both on 21 February 2023, highlighted the differences between the West and Russia on how they viewed the developments in the past year. As both leaders doubled down on their commitments, the common message was that this conflict will not end soon. As the Ukraine Crisis marks its first year, millions of its citizens have left the country and 100,000 military and over 30,000 civilian casualties have been recorded so far. The critical energy and economic infrastructure of the country are devastated. For Europe, Russian actions have strengthened the member states’ unity, revived and expanded NATO, and, more importantly, has led the Union to take some unprecedented decisions. This article highlights five key policy decisions taken by the European Union (EU) in the past year:

Re-aligning security

The crisis has led to renewed debates regarding the strengthening of defence structures within Europe. Developments have taken place at both the NATO and EU levels to completely overhaul their respective structures. To strengthen the alliance, NATO has been working towards bolstering its presence in the Eastern borders by increasing the number of its Enhanced Forward Presence (eFP) missions from four to eight; it has activated its rapid reaction force for the time and released its Strategic Compass in June 2022, which set its priorities for the next decade. However, the most important outcome of the conflict has been the shedding of neutrality by Sweden and Finland, leading towards the prospects of NATO’s expansion towards Northern Europe.

For its part, the EU has worked towards providing military assistance to Ukraine through its European Peace Facility. Under this, the EU has, so far, committed 3.6 billion euros in military assistance financing for Ukraine, including for lethal equipment (3.1 billion euros) and nonlethal supplies (380 million euros). It has also established a Military Assistance Mission in support of Ukraine (EUMAM Ukraine) to enhance the military capability of the Ukrainian Armed Forces. The total military aid from the member states is around 8.4 billion euros. At the national level, the member states responded by increasing their respective defence budgets, but the most important development was Germany letting go of its policy of not supplying weapons to war zones and re-committing 2 percent of its GDP towards its defence budget.

Diversification of energy becomes a possibility

The most fundamental change has been Europe’s shift away from reliance on Russian energy. In 2020-2021, the EU imported ‘29 percent of crude oil, 43 percent of natural gas and 54 percent of solid fossil fuels from Russia’—spending over 71 billion euros. To reduce their reliance, the EU and its member states took three important steps to respond to the challenge.

First, along with its allies, the EU imposed sanctions on the energy imports from Russia—banning all forms of Russian coal, seaborne crude oil, and petroleum products in its fifth and sixth rounds of sanctions. It also agreed with the G7 countries to implement a price cap on seaborne petroleum products, which originated in or were exported from Russia.

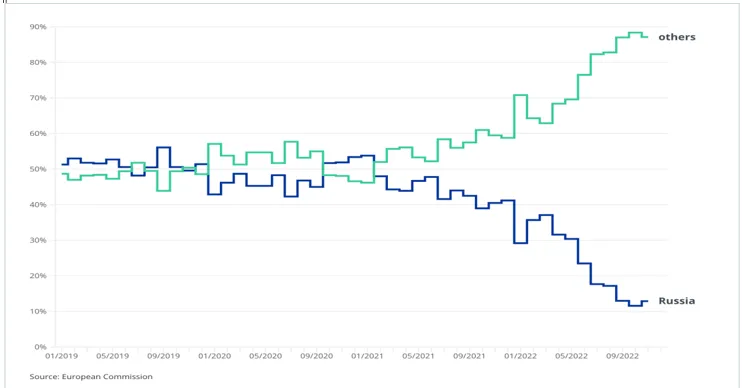

Second, they worked towards diversifying their resources away from Moscow by securing alternative supplies of energy from other countries like the United States (US), Norway, Azerbaijan, Algeria, Japan, Qatar, etc. Measures were also undertaken by the individual member states in securing energy deals with resource-rich countries. A key example of this is the signing of 15 years agreement between Germany and Qatar for LNG exports. These countries are also in the process of developing new LNG terminals over the next decade. The EU, in March 2022, had also declared that it would cut gas imports from Russia by two-thirds within a year. So far, the member states have successfully reduced their dependencies on Russian gas to less than 20 percent by November 2022.

Image: EU’s Gas Supplies

Source: European Council

Source: European Council

Third, in continuation with its Green Deal and Fit for 55 Agenda, the EU put forward its ambitious RePowerEU Plan in 2022, which laid out a blueprint for reducing its dependence on Russian fossil fuels. The aim of the plan is to accelerate the Union’s transition towards clean energy and scale up its renewable energy capacities in power generation, buildings, transport, and industry. The plan includes amendments to its flagship environmental package, the EU Green Deal, and covers three main areas: Energy saving, diversification of supply, and an accelerated transition to renewables.,

Attitude towards migration

Migration has been the most divisive issue among the member states of the EU. Europe has faced waves of illegal migration which have, at times, escalated to crisis level, for example, the 2015-16 migration crisis. As the issue remains most politicised within member states, the EU has been unable to either reform the Dublin Regulations or formulate a comprehensive policy on migration.

However, as the Ukraine crisis began and Ukrainian citizens started arriving in the EU member states, the Union initiated its Temporary Protection Directive for the first time. This directive was adopted by the EU in 2001 as a response to the large-scale displacement due to conflict in the Western Balkans, particularly in Kosovo and, Bosnia and Herzegovina. However, it was never used. Under this directive, member states have granted immediate protection to the Ukrainian refugees and bypassed the asylum systems in place to offer fast-track access to residence permits, social welfare, healthcare, education, and the labour market. The activation of the directive was termed as ‘unprecedented’ and ‘historic’ and, so far, 4 million Ukrainians have benefitted from the temporary protection mechanism and resettled across the EU countries—with Germany and Poland each hosting over 900,000.

Under this directive, member states have granted immediate protection to the Ukrainian refugees and bypassed the asylum systems in place to offer fast-track access to residence permits, social welfare, healthcare, education, and the labour market.

The activation of this directive marks a deviation in the response of the member states towards migration. As was witnessed during the 2015 crisis, many member states had opposed the idea of burden sharing leaving the front-line states extremely overwhelmed. However, it also raised questions related to discrimination regarding non-European third- country nationals seeking asylum.

Unity within the Union

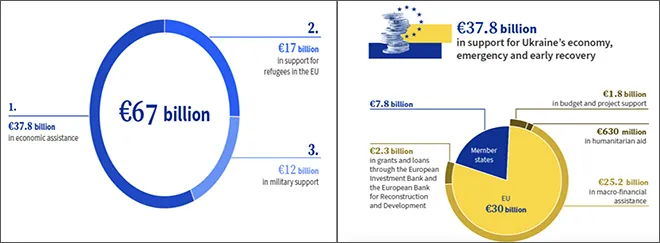

In a recent interview, High Representative Josep Borrell said, “It hasn't always been easy... Some complained, others disagreed, but, in the end, we maintained the unity we needed”—highlighting the continuing efforts to maintain unity among the member states as they respond to the crisis next door. So far, the EU along with its allies, have imposed nine rounds of sanctions on Russia—many of these have been implemented for the first time such as sanctions on Russian crude oil and coal; expulsion of Russian banks from the SWIFT international payment system; implementation of G7 price cap on Russian crude oil; expanding export control on technologies and banning exports in aviation, tech and maritime sectors, among others. In terms of aid to Ukraine, as of February 2023, the EU and its member states have provided a total of 67 billion euros including 37.8 billion euros in economic aid; 12 billion euros for the military; and 17 billion euros in support of Ukrainian refugees.

EU’s Aid to Ukraine

Source: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/infographics/eu-assistance-ukraine/

Source: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/infographics/eu-assistance-ukraine/

However, the exceptional move has been discussions on the possible investments of frozen Russian assets towards the reconstruction of Ukraine. A joint assessment of the World Bank, the EU, and Ukraine in September 2022, had estimated that the cost of recovery and reconstruction of Ukraine would amount to 349 billion euros, however, this figure is expected to be revised as the conflict continues. Member states such as Poland and Baltic countries are pushing the EU to use ‘Russia’s 300 billion of frozen central bank reserves’ to help in the reconstruction of Ukraine. While the EU is stepping up its discussions, the proposal remains problematic largely due to the lack of any legal framework and precedent.

Shifting balance?

The conflict in Ukraine has exposed the fundamental difference in the narrative between Western and Eastern Europe over the EU’s policy towards Ukraine and Russia. There is a growing divide between the front-line states—Poland and Baltic countries—and Western European countries such as France and Germany over the EU’s response to the crisis. Since the beginning of the conflict, Eastern Europeans have been the most proactive in their support to Kiev—in military assistance, imposition of sanctions, refugee rehabilitation, etc. While France and Germany have sent mixed signals over Russia—where they appear torn between maintaining ties with Moscow on one hand and maintaining unity among the member states on the other. The Eastern European states appear to be at the forefront of formulating the policy response of the EU towards Russia. Apart from supporting Ukraine, these states are also working towards bolstering their own defence structures as well as are vocal regarding the strengthening of NATO’s deterrence capacities in the region.

Despite the unity forged in the crisis, comprehensive policy outlooks in terms of economic recovery, security architecture, or reconstruction of Ukraine have yet to materialise

Once the conflict settles, for western Europe, any consideration of security architecture will involve Russia in some form, while for eastern Europe, security is about defending themselves against possible Russian intervention. These traditional fault lines within the Union will not disappear any time soon and will continue to define how the policy towards Ukraine and Russia is steered.

Conclusion

Jean Monnet had written that Europe will be built through crises and it would be the sum of their solutions, implying that crisis is neither new to EU nor is it challenging the EU’s unity. However, the crisis in Ukraine has resulted in more than just unifying the EU—it has led the neutral states to reconsider their status; caused the strengthening of NATO’s defence and deterrence; forced the EU member states to bolster their own respective defence structure on one hand and to strengthen EU’s structures on the other. For its part, the EU has taken some unprecedented measures including activation of the European Peace Facility and the Temporary Protection Directive, and imposed severe sanctions on Russia. There is a kind of strategic awakening within the EU, with new players shaping the European narrative and policy. The earlier assumptions of weak response from the EU have not come to pass. Rather, the Union has shown exemplary unity and resolve in its response towards the crisis.

In short, the crisis has led to the emergence of a strengthened EU and NATO. However, despite the unity forged in the crisis, comprehensive policy outlooks in terms of economic recovery, security architecture, or reconstruction of Ukraine have yet to materialise. And with Russia suspending the New Start Nuclear Arms Treaty, potential use of nuclear weapons and the danger of escalation through miscalculation remains a real possibility.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Ankita Dutta was a Fellow with ORFs Strategic Studies Programme. Her research interests include European affairs and politics European Union and affairs Indian foreign policy ...

Read More +