The United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan (UNCIP) Truce Terms proposals in early 1949 were a matter of great import for both the Government of India and the still to find its feet Government of J&K. Kickstarting the process of providing vital inputs on the contentious proposals was Sheikh Abdullah. On May 3, 1949, he sent his data points to Sardar Patel making it clear how the delineation of ceasefire lines would take place and how it would impact Indian forward positions militarily and strategically which had fought bravely to repulse the raiders and Pakistan Army regulars from Indian soil. Sheikh wrote highlighting the problems emanating from the terrain and topography in the border areas: "If they are accepted the Truce Line in the north and northeast will be a very vulnerable one. The enemy will command numerous foot paths and pony tracks leading into the Valley and there will be a regular and steady flow of infiltration of armed hostiles. In fact, the enemy has already started this between Keran and Gurez. The attendant consequences on the morale of the people will be extremely unfavourable, it will also create an acute problem with regard to maintenance of law and order. We must stick to the stand that we took up in March regarding the Truce Line; at any rate, we should not budge from the position taken up in Girija Shankar Bajpai's letter of April 17 that we should garrison the main strategic points."

In the light of PM Modi's counter offensive on Gilgit and Baltistan, it is important to comprehend how the Truce Lines were demarcated. Those were trying days, for every inch in Kashmir mattered due to the porous nature of the terrain. Something that India is grappling with even today.

He went onto say, "Commission has not agreed to the disarming and disbandment of the Azad Forces. Their suggestion that this question should be taken up for consultation immediately on acceptance of Truce Terms is entirely unsatisfactorily. As they have worded their terms, consultations will start not only in regard to the disarming and disbandment of the Azad Forces, but also in disposal of the Indian and State Forces.. The terms are totally unacceptable. As the Commission has closed the door for further negotiations, I am afraid, we shall have no alternative but to inform the Commission that we cannot agree to the terms."

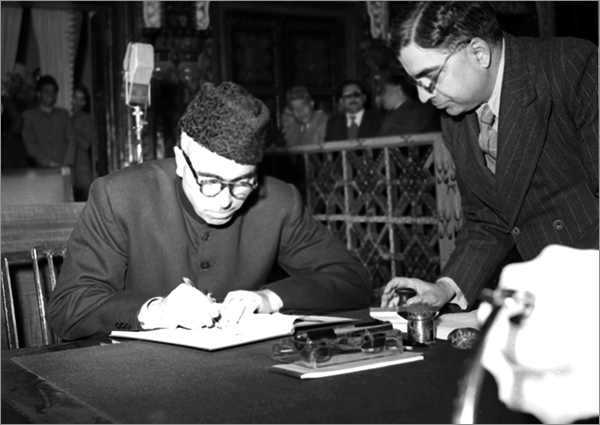

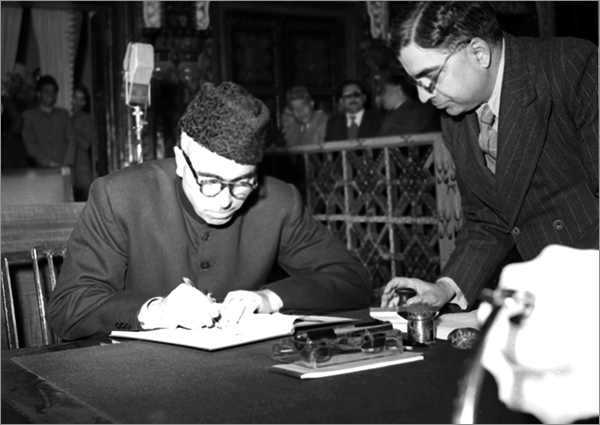

Sheikh Mohammed Abdullah signs the Members Register of the Kashmir Constituent Assembly on October 31, 1951. Courtesy: Public.Resource.Org/CCBY 2.0

Sheikh Mohammed Abdullah signs the Members Register of the Kashmir Constituent Assembly on October 31, 1951. Courtesy: Public.Resource.Org/CCBY 2.0

What is it that Sheikh and his government were arguing so vehemently for? This he went on to explain graphically and most lucidly. Interestingly the Government of India and Government of J&K were on the same page on these sensitive territorial matters, acting as a cohesive whole, and not running each other ragged.

In the Memorandum of the UNCIP sent along with the secretary general's letter dated March 28, 1949, the Government of India asked that the line should be along the Kishenganga River from Keran to Shardi, and run north thereafter, so as to include within our line the Gilgit Wazarat and the territories to the northeast of the State. In the secretary general's letter dated April 17, 1949, this demand was modified to a considerable extent and the Commission was asked to the garrisoning of strategic points.

Even to this modified request, the Commission has not agreed, on the ground that 'achieve the purpose of the Truce, it is essential to restrict the field of military activities as far as possible.. The UNCIP also proposes that we fall back to the line from Chorwan to Dras. During winter some of our forward pickets had to be withdrawn. Pakistan has utilised this opportunity to occupy positions which it did not have before the cease fire.. If the line is to be drawn from Chorwan to Dras, it will enable the enemy to command numerous footpaths and pony trails into the Valley.. We must reaffirm our earlier stand that the authority of the State has not been challenged or disturbed in this area, except by roving bands or hostiles in some places like Skardu, which have been occupied by Pakistan irregulars.

Correspondence flew thick and fast. As India attempted to formulate an overarching strategy to deal with Pakistan and the Truce Terms, on May 9, 1949, a crucial meeting was held Western Command HQ helmed by Lt. General S. M. Shrinagesh and Secretary Kashmir Affairs Vishnu Sahay and Deputy Chief Minister J&K Bakshi Ghulam Mohd to take stock of the situation vis-à-vis the border. Among the issues discussed here was the military complications in the Truce Line following the range of hills suggested in the Lolab Valley instead of the Kishenganga river. It was explained that infiltration across the Kishenganga was more difficult than across the range of hills as crossing places in the case of the former were few. This meant that a lesser number of troops would be required in the area if Kishenganga river was the dividing line than if it was decided to have it further south along the range of hills.

What were the problem areas surrounding the significance of the Truce Line? What did it represent? Was it a ceasefire line beyond which our Army could not advance? There were several inconsistencies which in any case created more consternation.

Let us examine the facts. The responsibility of safeguarding the 'security of the State', after implementation of Parts 1 and II of the UNCIP's resolution which postulated the withdrawal of all tribesmen and Pakistani nationals who entered the state for the purposes of fighting and the Pakistan Army was to rest with the Indian and State Forces.

Did the expression 'security of the state' mean the entire state, in which case our Army could have advanced to the frontier of the State as it was in September 1947 before the disturbances broke out? If this position had been conceded, then the drawing of the Truce Line had no military significance. It only demarcated a particular area which was to be under the administration of 'local authorities' who in any case were to act under the surveillance of the UNCIP.

On the other hand, if the expression 'security of the State' was to be interpreted as meaning the security of the area now held by the State, then it became necessary that the Truce Line be such that it could be militarily defended and include such areas as were necessary for purposes of administrative necessity.

Against this backdrop, after much internal confabulation, the Government of India was keen for the restoration of the block of territories from:

- Jhangar to Haji Pir Pass in the southern sector,

- Kathai right bank of the river Jhelum to Tithwal,

- Tithwal to Shardi on the west bank of the river Kishenganga

On the first point, the Government of India's thinking was whether India should reopen the question. After all, it was viewed that from a military point of view, the line drawn from Jhangar to Poonch may have been all right, but from the Indian viewpoint, it would present tremendous difficulties. The view was that, "Unless the line runs along an easily recognisable hilly or river feature, it is difficult to regulate the flow of people from one area to another or to have effective and efficient administration. The tehsil of Mendhar has been cut into four bits; two with the state and two on the other side. These intersect each other and unless the whole area is compact and administered by one authority, there will be difficulties. The same problem existed with regard to north of Poonch and right up to Shardi.

Kashmir Valley could not be easily defended according to military strategists unless India controlled Haji Pir Pass. For Gulmarg, Shopian and Saran valley were directly under its controlling path. India did not realise the strategic importance of the Haji Pir Pass and handed it back to Pakistan after the army valiantly recaptured it in 1965. India returned the pass to Pakistan at the Tashkent talks brokered by Russia to end the Indo-Pak war of 1965. General Harbaksh Singh ordered his men to launch a two-pronged attack on the Haji Pir pass to capture the entire bulge and cut off the main route for the infiltrators from Pakistan which was an integral part of Pakistan's Operation Gibraltar.

The same underlying principles governed India's thinking on Kishenganga Valley. Why was the Kishenganga Valley so important strategically to India? The Kishenganga valley starts from Sonmarg and ends at Domel in the Muzzafarabad district now in Pakistan occupied Kashmir. The important places in the Valley are: Gurais, Folowoi, Doarain, Keran and Tithwal. At Tithwal, the Valley is about 2500 feet high, it rises to 3500 feet at Keran to 500 feet at Kal; to about 8000/9000 feet at Gurais and about 13000 feet near Sonmarg. Pony tracks run along the river, sometimes on the right bank and sometimes on the left bank. Tithwal, Keran and Gurais are connected by jeepable roads with Kashmir Valley.

Why was the Kishenganga Valley strategically so important to India?

The mountains on the left bank of the river towards Kashmir Valley are not so high, while mountains on the right bank (which came to be occupied by Pakistan troops) are high and seal off the Kishenganga Valley from the adjoining district in the NWFP. In fact, from Tithwal onwards communication between Kishenganga Valley and the adjoining Kagan Valley used to be blocked nine months of the year.

In light of all this, Pakistan could not be trusted by the Indian or J&K State Governments (remember till 1953, it had a Prime Minister of its own in Sheikh Abdullah). There were numerous breaches of the cease fire agreement. Even after January 1, 1949, border raids continued with a persistence, which revealed that they were not just by design but premeditated. The Indian Army was told about these incursions from time to time. The State Government reckoned that the raids constituted a flagrant breach of the cease fire agreement.

It was a tenuous and uneasy truce where Pakistan was constantly up to its tricks. Bakshi Ghulam Mohd, Deputy PM of J&K provided a detailed exposition of how these breaches were being conducted systematically like pinpricks. On March 25, 1949, he wrote to Vishnu Sahay, secretary Kashmir Affairs:

All along the border, particularly in the northwest and southwest, a systematic infiltration of enemy agents is going on. Small bands of trained agents are being deputed and asked to settle down at various places in the State. The places where concentration of these enemy pockets has been reported are:

Tithwal Guraiz sector

- Dudhwal

- Duwarian

- Jhanda

- Phulwoi

- Rashian Gali

- Totmar Gali

Uri and Poonch sector

- Noorpur Gali and adjacent places

- Suran valley

Mandhar and Janghar sector

- Towards Rajouri, Mendar and Chingas

...In the Northern Areas, in Gilgit and Skardu, particularly old revenue and other records, as also any other evidence which would establish the fact that Pakistan has been directly governing and administering the area, are being destroyed. These records are now being replaced by cooked up and fictitious figures and documents to show the UNCIP that the area, instead of being governed and controlled by Pakistan, as made out in our statements, was directly governed and controlled by the so called Azad Government.

The great State of J&K originally had five parts to it — unified it was bigger than France at the time of Independence — Jammu, Kashmir, Ladakh, Aksai Chin and Northern Areas (Gilgit-Baltistan). Over time, India has lost the Northern Areas, Aksai Chin to China and of course the part captured by the tribal raiders in October 1947, which Pakistan chooses to refer to as Pakistan Occupied Kashmir, which incidentally includes the Gigit-Baltistan area garnered courtesy a quietly executed British coup. There is also Shaksgham Valley, which in 1963, Pakistan handed over 5800 square kilometers of territory of Gilgit-Baltistan to China without the consent of the local people.

And so it has carried on as India and Pakistan have traded charges and fire. In the end, the events of 1947-49 left a truncated J&K behind for India and scars which haven't healed till this day. The eyeballing though continues unabated.

Read more on Kashmir by the author:

Calling the intransigent bully’s bluff

India still playing catchup with Pak’s propaganda on Kashmir?

Kashmir: No algorithm for Azadi

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Sheikh Mohammed Abdullah signs the Members Register of the Kashmir Constituent Assembly on October 31, 1951. Courtesy:

Sheikh Mohammed Abdullah signs the Members Register of the Kashmir Constituent Assembly on October 31, 1951. Courtesy:  PREV

PREV