This article is part of the series — 2021: The Year of Vaccines.

This article is part of the series — 2021: The Year of Vaccines.

One of the most successful public health interventions in contemporary human history, vaccinations have aided the world in eradicating multiple diseases and brought many others to the brink of elimination. It saves

2 to 3 million lives each year from diseases such as tetanus, influenza, measles and diphtheria. Not only are vaccines critical for preventing infectious diseases, but also for controlling the severity and spread of such diseases.

The pandemics of the past have taught us the rarity of a vaccine to be developed in less than five years. Nevertheless, in 2020, the world found itself in a race against time to develop and deliver vaccination against the novel coronavirus. The targeted timeline for creating a vaccine for COVID-19 was pegged at 12 to 18 months. However, within one year of beginning research, more than half a dozen vaccines have been approved, and several are near approval for emergency mass use.

As the world picks up pace on the biggest vaccination campaign in global history, many fear that the road ahead will not be easy, particularly since the poorer countries are left with very few doses, if any, even months into the campaign.

India, with one of the largest immunisation programmes in the world, has an annual

estimated number of 26.7 million newborns and 29 million pregnant women. Despite steady progress in vaccine coverage,

38 percent of infants in India failed to receive all basic vaccines within the first year of their birth in 2016. Ensuring widespread access to effective COVID-19 vaccines in a country as vast is crucial.

Many fear that the road ahead will not be easy, particularly since the poorer countries are left with very few doses, if any, even months into the campaign.

The

first phase of India’s vaccine campaign consisted of vaccinating 10 million health care workers, 20 million frontline workers, followed by the second phase of vaccinating

270 million priority groups — largely consisting of the elderly population and those with comorbid conditions. In March 2021, the country initiated the second phase of the vaccine process, with two key vaccine candidates — Oxford-AstraZeneca’s CoviShield and Bharat Biotech’s Covaxin.

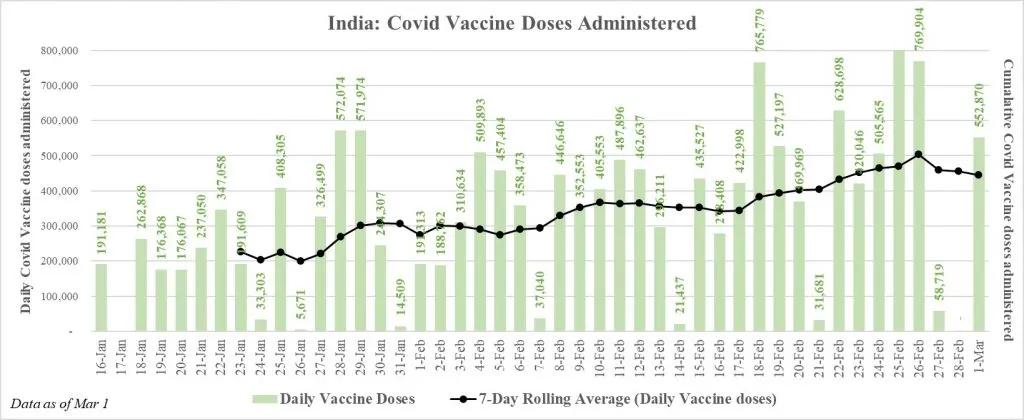

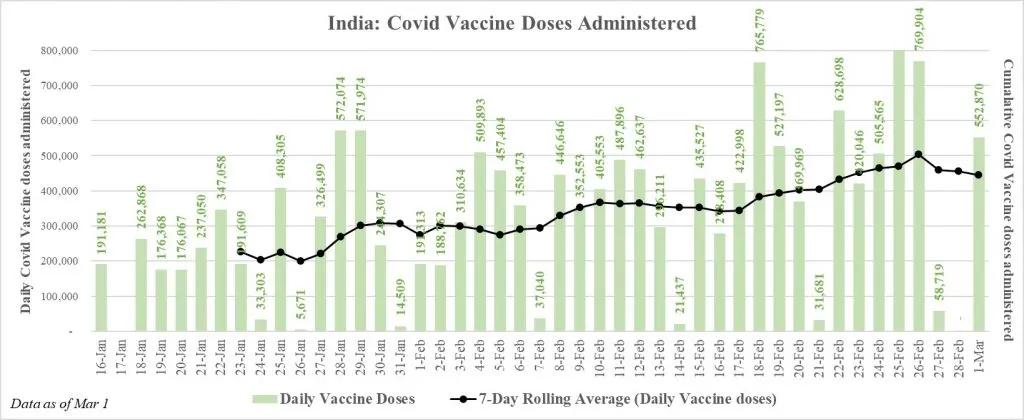

By 1 March 2021, India has vaccinated a total of

14.8 million people. The average daily rate of vaccines is 337,594. Though India has been steadily increasing its vaccine coverage in the past few weeks, to ensure equitable distribution of the vaccine, Indian policymakers must address key challenges associated with vaccine hesitancy and vaccine logistics, as the pace of the rollout has been much lower than necessary.

The challenges to India’s COVID-19 vaccine rollout

I. Distribution and supply chain challenges

One of the most complicated tasks associated with this pandemic will be the efficient deployment of the vaccine, which requires smooth coordination and collaboration at multiple levels. Given its experience with its various communicable diseases, India has been relatively adept at handling national immunisation programmes. However, these initiatives were meant specifically for children and pregnant women, and a life-cycle immunisaton programme, as that of COVID-19, will require a different, broader structure and larger-scale operations.

Manufacturing the vaccines and other necessary components

As most global vaccines require a double dosage per person, in the first phase alone, India will require up to 600 million dosages. The Serum Institute of India (SII) currently holds the capacity for

producing 1.5 billion doses, followed by Biological E. and Bharat Biotech, with 500 million doses each, and companies like Zydus Cadila, which can produce 150-200 million doses. However, as the ‘pharmacy of the world,’ India exports about

74 percent of the 2.3 billion doses of vaccines it produces each year. Thus, vaccinating its population will also require exploring the feasibility of procuring a global vaccine for the Indian population at a reasonable rate.

In the first phase alone, India will require up to 600 million dosages.

While India is a key producer of vaccines for the world, it is important that the country ensure a safety net for its citizens, while also supporting the global community. Currently, India has ensured

procurement of 2,200 million doses of vaccine — 1,000 million of the Oxford-AstraZeneca, 1,000 million of the Novavax and another 200 million of the Gamaleya vaccine candidate — in addition to producing the Bharat Biotech vaccine in the country. Of these, only the first has received regulatory approvals.

Additionally, it is equally important for the Indian government to facilitate access to the necessary and irreplaceable components that will play a significant role in vaccine production and delivery, such as syringes, glass vials, and prerequisite medical devices.

Assuming a double dosage for about 300 million people, there is a requirement of more than 600 million syringes in the first phase alone. India is the biggest exporter of syringes in the world, with a capability of producing over

1 billion syringes for vaccination on a yearly basis. With adequate incentive and assurance from the government, the syringe makers in India will be able to expand production to up to 1.4 billion; however, over 50 percent of this is being earmarked for exports. In December 2020, the Government of India (GoI)

ordered an additional 830 million syringes for the COVID-19 vaccination drive, and invited bids for 350 million.

Logistics, supply chain and transport of the vaccine

The most critical component of vaccine deployment is the temperature-controlled equipment and procedures that are used to maintain the integrity of vaccines. These include the storage facility at the manufacturing hub, the transportation facility, and the storage facility at the point of vaccine administration.

As per the National Health Mission, India’s Universal Immunisation Programme (UIP) consists of

28,947 running cold chain points. Of these,

~97 percent are located at below district levels, while the rest are located at or above district levels. These further consist of ~

85,634 cold chain storage equipment managed by ~55,000 specialised technicians. These centres are responsible for the provision of

390 million doses of vaccines to newborns, infants and pregnant women on a yearly basis.

India would require at least 10 times the number of facilities operating currently — i.e., almost 800,000 cold chain units.

While these units run a vast and successful immunisation programme, administering vaccines to an additional 300 million people in the first phase of the COVID-19 vaccine project, with time-bound multiple dosages per person, seems a difficult task. According to

industry estimates, in order to conduct an efficient and effective vaccination drive for COVID-19 over and above the current UIP, India would require at least 10 times the number of facilities operating currently — i.e., almost 800,000 cold chain units. Not only will this require increasing the number of facilities in highly populated districts to reach more people, but also setting up and penetrating the smaller towns and villages.

Moreover, once the vaccine is manufactured and ready, the daunting task is reaching the people, especially those living in India’s remote villages. This requires adequate vaccine transportation facilities which will have the appropriate temperature-controlled storage units.

The global coverage of vaccines over the next two years alone

will require 200,000 movements by pallet shippers across 15,000 flights. The task will entail

15 million deliveries to be shipped in appropriate cooling boxes. Furthermore, reaching distant locations within the rural areas of India, at some stage, would require approximately

11,500 refrigerated trucks. Not only is this a logistical challenge, but also a financial one, and India will have to ramp up capacity at a steady and rapid pace, while maintaining quality checks.

Once the vaccine is manufactured and ready, the daunting task is reaching the people, especially those living in India’s remote villages.

Lack of adequate medical personnel

Across the world it is acceptable for pharmacists to administer vaccines; but such is not the case for India, where only doctors and trained nurses are permitted. Today, India has

3.07 million nursing personnel, translating to a ratio of 1.7 nurses per 1,000 population — this is far below WHO norms of 3 per 1,000. India’s registered allopathic doctors were a meagre

1.2 million, as of September 2019. Given that the health personnel in the country are already overburdened by the pandemic, the government has opted for a site-based vaccination drive, wherein sessions are being conducted from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.

However, an intense and important programme as this calls for innovative responses to counter the lack of medical professional capacity. Effective utilisation of Health and Wellness Centres and Primary Healthcare centres that are spread throughout the country is a plausible plan. Similarly, India consists of a comprehensive network of over one million Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) and 2.5 million anganwadi workers who help provide medical assistance to women and children in villages and towns. Employing infrastructure can be helpful in reaching the priority population in the distant regions of the country.

II. Vaccine hesitancy and misinformation

The final aspect that may arise as a challenge as we progress is the people and the community. At present, the discourse surrounding the vaccine trials has been closely watched and interpreted by media and individuals. This has led to a plethora of misinformation, especially on social media platforms, causing fear of the vaccine. The

early approval of India’s homegrown Covaxin has further raised concerns regarding the safety of its usage.

Experts worry that the trend may further spread to the other members of the community, especially due to the anxiety and stigma surrounding it.

This has led to many healthcare and frontline workers

refusing the vaccine, which has been one of the key reasons for the slow turnout of the vaccine drive in India. For instance, the

target doses till 28 February were 30.6 million, but only 12.7 million doses were administered till then. As the second phase of the vaccination drive begins, experts worry that the trend may further spread to the other members of the community, especially due to the anxiety and stigma surrounding it.

The Indian government must organise community sensitisation drives to educate people and eliminate challenges pertaining to vaccine hesitancy. These programmes will be especially important in areas with higher populations with low levels of literacy and socio-economic status. Also, the government must ensure that those elderly and high-risk populations living in far-flung areas away from any public or private health care facilities are not left behind in the vaccination drive. With senior ministers and bureaucrats opting for Covaxin and giving wider publicity to their vaccination, the government of India is trying to fight vaccine hesitancy among the public. Videos and photographs of overcrowding in Mumbai’s vaccination centres indicate that the perceived vaccine hesitancy in the first phase had a lot to do with the low number of daily cases in the past. With a surge in cases in sight across many Indian states, the demand for vaccines is bound to shoot up, and present the country with another dilemma: Whether to vaccinate Indians quickly, or to control the pace of the vaccination drive in a way that allows substantial exports of vaccines?

India has been rigorously attempting to vaccinate its priority population, efforts have produced slower than expected results. Reportedly the country aims to increase the average rate of doses to five million a day in the coming weeks. Although the public health system in India has been performing well the past few weeks, India requires the strategic aid of its private medical sector to reach its vast and segregated population.

The involvement of private firms and institutions will also significantly enhance the infrastructural and logistical capability of the vaccine programme.

The private medical infrastructure in India can aid the vaccination of over

500 million people in less than six months. With the initiation of the second phase of the vaccination, the private institutions empaneled under the Ayushman Bharat or PM Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY) have started the vaccination sessions. Not only will the involvement of private firms and institutions provide the necessary boost in the society’s confidence of the vaccines, but also, significantly enhance the infrastructural and logistical capability of the vaccine programme. This critical modification in the vaccine process may be the key to a successful COVID vaccine programme in India.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This article is part of the series —

This article is part of the series —  By 1 March 2021, India has vaccinated a total of

By 1 March 2021, India has vaccinated a total of  PREV

PREV