-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

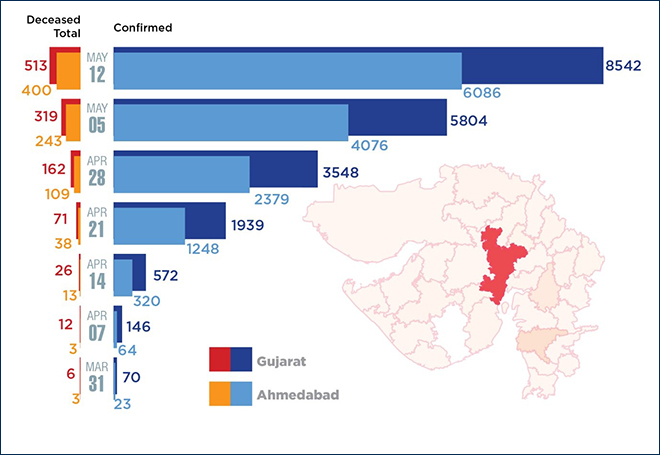

As of 13 May, 537 people have died due to Covid-19 in Gujarat, which has 8903 confirmed cases and is the second most infected state in the country after Maharashtra. In Gujarat, Ahmedabad remains a matter of concern as the city’s confirmed cases stands at 6353, approximately 71 percent of the state’s total cases. Over 400 people have died in Ahmedabad due to the virus. While the rising number of cases and deaths in Ahmedabad is a matter of concern, several questions pertaining to the rapid spread across the city remain unanswered.

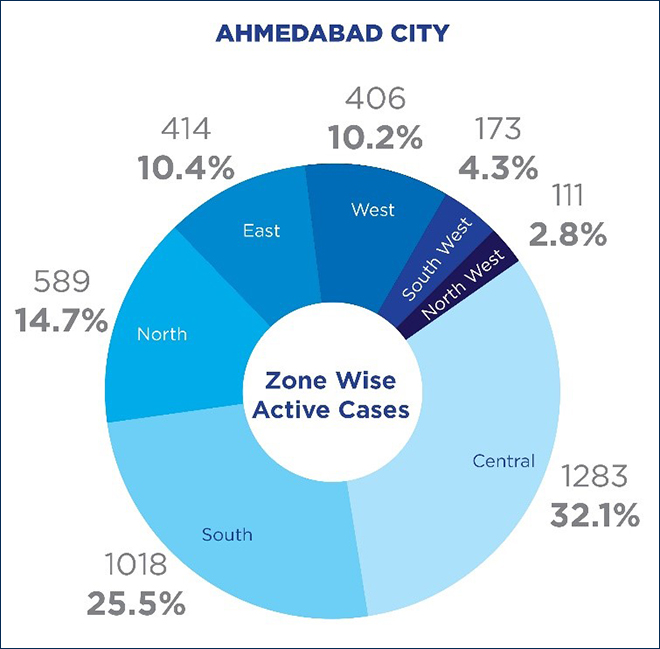

The first Covid-19 case in Ahmedabad was reported on 17 March 17. By the end of the month, the city had a mere 25 confirmed cases with three deaths. The spread of the virus cannot be blamed on international travelers as the Centre had suspended general foreign flights from 15 March, while flights for Indian stranded abroad were suspended from 21 March. By 13 April, the city had only 282 confirmed cases, out of which 27 and 15 cases were through domestic and international travel, respectively. The rest of the cases were local transmissions in the walled city of Ahmedabad (central Ahmedabad), which can be directly/indirectly linked to the Tablighi Jamaat Markaz held in Delhi’s Nizamuddin.

As the outbreak of Covid-19 was within the walled city area, several measures were taken to contain its spread— the Nehru Bridge was closed to restrict movement, a two-week curfew was imposed, and intensive surveillance and testing was carried out. Despite these measures, the virus spread from the central and south zones to the other parts of the city.

Source: As of May 12, 2020, Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation

Source: As of May 12, 2020, Ahmedabad Municipal CorporationThe Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (AMC) and the state government have acted quickly to contain the spread of the virus. However, there is much uncertainty around the policy measures implemented and the on-ground reality since the increase in confirmed cases and fatalities exhibit a contrasting picture. One cause could be the choice of policy measures and their late implementation, since the outcomes contradict policy adherence and efficacy. Another reason is lack of cooperation at the community level.

Source: As of May 13, Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation and https://www.covid19india.org/

Source: As of May 13, Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation and https://www.covid19india.org/For instance, a centralised approached was adopted by the AMC, creating several bottlenecks for Covid-19 patients. On 6 May, the state government ordered all private clinics, nursing home and hospitals to open in the next 48-hours or lose their licence. Had clinics and primary healthcare centers—which are more accessible to the common people—been allowed to test and treat people from the onset, the severity of the virus spread could have been contained. This also impacted the mortality rate, as delayed treated coupled with existing co-morbidities had a severe impact.

The mortality rate in Ahmedabad has also been impacted by the tragic class divide. Covid-19 positive patients from the walled city are admitted at the Civil Hospital, where patients have complained about a lack of amenities and mistreatment from doctors and other staff. On the other hand, people who are better-off have been admitted in SVP Hospital or private five-star hotels, where the treatment is extensive.

This explain why on 3 May out of the total 185 deaths recorded in the city, 130 have been from the hotspots, with Jamalpur alone accounting for 69 deaths.

The delayed hospitalisation of people from within the walled city has also contributed to the increase in death rate. Co-morbid patients are certainly at high risk and constitute about two-thirds of total deaths. About 17.8 percent people die on the first day of hospitalisation, 22.1 percent on the second day, 19.3 percent on the third day, 10.4 percent on fourth day, 9.2 percent on the fifth day and 3.8 percent on the sixth day. Only 14.9 percent and 2.5 percent have stayed between seven to 10 and beyond 10 days, respectively. Given the increase in the mortality rate due to existing co-morbidities critical care centers are paramount, but are currently not functional at public or private hospitals.

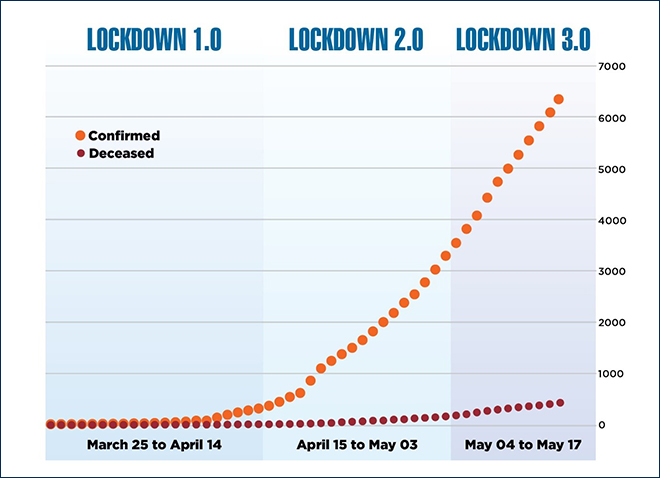

Source: As of 13 May, Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation

Source: As of 13 May, Ahmedabad Municipal CorporationThere is evidence that the late implementation of policies is delaying the process of containing the spread. The identification of fruit and vegetable vendors and provision and grocery stores as ‘super spreaders’ was done since 30 April. Fines were imposed on vendors not wearing masks, hand sanitisers and masks were distributed by the civic authorities, and 500 potential ‘super spreaders’ were screened per day in each ward. But there were still a large number of vendors who continued selling their products. An effort to completely curb the virus spread was made through a stringent lockdown being imposed from 7-15 May, with only milk and medicines being sold during this time. As of 10 May, 334 ‘super spreaders’ have tested positive, and one can only imagine the number of people who would’ve come in contact with them.

If a complete restriction was imposed when the ‘super spreaders’ were first identified, the spread of the virus could have been curbed.

A large percent of the cases were from within the declared hotspots in the central and south zones. An attempt to restrict the movement was made by closing the Nehru Bridge, but it wasn’t stopped entirely. On 4 May, five bridges (Dadhichi Bridge, Gandhi Bridge, Nehru Bridge, Sardar Bridge and Ambedkar Bridge) that connect the eastern and western zones to the central zones were closed. On 5 May, AMC Commissioner Vijay Nehra self-quarantined after coming in contact with Covid-19 patients, and was replaced by Gujarat Maritime Board chief Mukesh Kumar. Additionally, Rajiv Gupta was appointed as in-charge of Covid-19 activities in Ahmedabad and Pankaj Kumar was appointed as the supervisor of the health department. The Covid-19 situation was slipping away from the hands of the administrators, so why weren’t these experts brought in sooner.

There were also several policy flipflops. On 26 April, shops and establishments across the state were allowed to reopen, but in Ahmedabad they were asked to shut down around mid-day. Then vegetable vendors and grocery stores were closed from 7 May, a decision that was only announced a day before (6 May), leading to large crowds outside shops and vegetable vendors, with no adherence to social distancing measures and several people not even wearing masks.

There has also been a major shift in the testing protocols since the appointment of the new three-member committee. The initial strategy of intensive testing wherein primary contacts of a Covid-19 positive patient were also tested is no longer being followed. Before the new committee was introduced, a few people from the west zone tested positive on collection of random samples. The new guidelines say there will be no testing for asymptomatic patients. Ahmedabad has seen a direct correlation between the confirmed cases and the number of tests conducted. One is forced to wonder that at a time when Ahmedabad needs to correct its mistakes if the situation is being manipulated to bring down the numbers (by conducting fewer tests).

It is important to consider the economic, geographic and demographic facets of Ahmedabad’s various areas. In the walled city, population density must be taken into account when recommending social distancing and home isolation. The Centre’s guidelines for home isolation clearly state the need of a ventilated room. The walled city is spread over roughly 8.7 sq kms and is densely populated. In such a situation, home quarantine is not advisable. Further, as the walled city has seen more than 80 percent of asymptomatic cases, residents don’t appear to be worried by the Covid-19 virus and are not taking it as seriously as they should. This instigated a clash between the residents of the Shahpur area and the police when the police urged residents to stay indoors.

Several questions must be answered to arrive at the reasons for Ahmedabad being the thirs most affected city in India. Incidents like misplacing the records of approximately 90 people in a Covid-19 care center shows the weak administration of the government. The attention appears to be shifting towards keeping the harsh reality under cover rather than taking corrective measures. With the lockdown slated to end on 17 May, it is worth asking for how long people are expected to stay indoors. It is important to recognise that despite the lockdown, the authorities have failed to contain the spread.

While a lockdown can curb the virus from spreading, it certainly doesn’t kill it. The state government as well as the AMC need to create agile structures to bring together key decision-makers, surface and filter ideas, and guide implementation.

The coming days and weeks will be critical. Difficult decisions on how to lift lockdowns, curfews and other restrictions will need to be made based on the economic, social, demographic and geographic aspects of the city, because in some parts of Ahmedabad, even if people do not die due to the Covid-19 virus, they will certainly die of hunger.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Anushka Shah was Sub-Editor at ORF. Anushkas research interests include: climate finance urban environmental policy use of technology for socioeconomic development.

Read More +