-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

It is an opportune time to assess and take stock of the progress as well as the roadblocks confronted by the public healthcare sector. The challenge for the next government will be to find innovative and implementable healthcare delivery solutions.

As Meghalaya, the Northeastern state, goes to polls, two major political parties — the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Indian National Congress (INC) have been campaigning tirelessly in the state with a promise to improve healthcare. Addressing a rally last week, Prime Minister Narendra Modi referred to the “pathetic condition” of the healthcare sector in Meghalaya under the Congress’s rule. He went on to question whether there were doctors and medicines available in villages and claimed that “women are scared of going to hospitals and so they deliver babies at home at risk to their lives,” pointing to the low institutional deliveries. At the same time, the incumbent doctor-turned Chief Minister Mukul Sangma was quoted saying: “We have been able to deliver despite the challenges. It was transparent and our delivery system has implemented the promises.”

With health becoming a highly contentious and crucial subject for this election, it is an opportune time to assess and take stock of the progress as well as the roadblocks confronted by the public healthcare sector in the state.

Meghalaya, with a population of 29,66,889 across seven districts (as per Census 2011 and the National Family and Health Survey-4), is unique in terms of its population composition. A tribal state, with over twice the population of Bahrain, Meghalaya is dominated by three tribes — Khasi, Garo and Jaintia — all of which are matrilineal and therefore, presumably matriarchal.

Although Meghalaya is poorer than the average Indian state, its per capita health expenditure (₹2,366) is among the top 10 states with highest health spending. The percentage of households in Meghalaya with any member covered by a health scheme or insurance stands at 34.6%, compared to the national average of 28.7%. While there is still a large population that is yet to be covered (the goal is to cover all households), it is definitely a major improvement for the state which only had 0.7% coverage in 2005 (NFHS3).

However, the coverage varies greatly across the districts — as high as 56.2% in the South Garo hills and 56.9% in the Jaintia hills, to 18.3% in the East Garo hills. In order to extend financial protection and universal health coverage (UHC), the Congress led state government launched ‘Megha Health Insurance Scheme’ in 2012, aimed at providing health insurance coverage of ₹2,80,000 for up to a family of five members. This flagship scheme “is not confined to BPL families” but has been “extended to everyone”.

Unlike most Indian states, Meghalaya is considered “ideal” as both sex ratio at birth and sex ratio of last child are close to the benchmark.

According to the Labour Ministry’s report, prevalence of unemployment in Meghalaya is approximately 4.8% — lower than the national average. Literacy levels are remarkable, with female literacy almost 25% higher than the average female literacy rate in the country. 91.4% of married women (15-49 years) participate in household decisions and 57.3% own a house/and or land, almost 20% points higher than the national average.

The percentage of households with electricity (91.4%) improved by 20% points and households with improved sanitation facilities shot up by almost 25% points over the past decade. Yet, 40% of households in the state lack access to improved sanitation facilities.

Unlike most Indian states, Meghalaya is considered “ideal” as both sex ratio at birth and sex ratio of last child are close to the benchmark. According to NFHS 4, total sex ratio at birth in the state is 1,009. In other words, there are 1,009 females per 1,000 males (for children born in the last 5 years), making women more than half the state voters.

While these figures may be impressive and point towards high levels of gender equality, a closer look reveals that this trend is not uniform across the state. The sex ratio at birth in urban Meghalaya is 891 (lower than the Indian average) whereas in rural Meghalaya is as high as 1,030. In general, prevalence of sex selection tends to be higher in urban areas due to better access to technology like sonogram and sex determination tests — a possible explanation for the extreme urban-rural discrepancy.

Inspite of being a matrilineal society, which tends to project a very progressive picture, there has been a stark rise in the violence against women. While spousal violence has declined by almost 10% points in India, there has been over a 10% point increase in the number of women reporting cases of spousal violence in Meghalaya. Clearly, something seems to be amiss.

In terms of key health indicators, the latest available data on infant mortality rate (IMR) points to a worrisome situation in the state. With 39 deaths per 1,000 live births, Meghalaya’s IMR is higher than the national average of of 34. Further, rural IMR (40) in the state is almost 15 points higher than the urban. However, Meghalaya has shown tremendous improvement in under 5 mortality rate (U5MR). While both India and the state’s U5MR were almost the same a decade ago, Meghalaya managed to reduce it by 30 points ever since.

While spousal violence has declined by almost 10% points in India, there has been over a 10% point increase in the number of women reporting cases of spousal violence in Meghalaya. Clearly, something seems to be amiss.

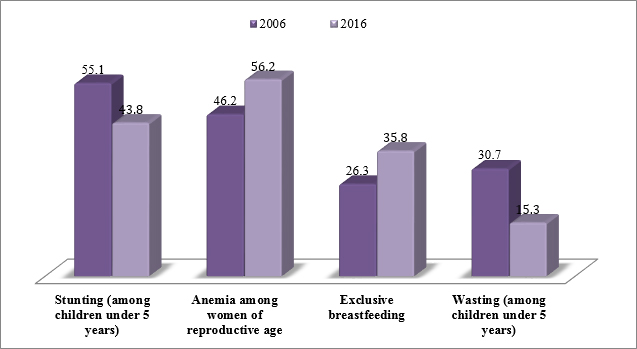

Overall, there has been progress in nutrition outcomes in the state between 2006 and 2016 (figure 1.0). The prevalence of stunting (among children under the age of five years) reduced between 2006 and 2016. However, it still continues to remain higher than India’s average of 38.4%. Interestingly, there is variation in stunting levels within the state, ranging from 16.8% in the South Garo hills (also among the top 10 districts with lowest rates of stunting in India) to 51.6% in Ribhoi. Wasting in children (weight for height) under the age of five reduced by half over the last decade and is lower than the country’s average of 21%.

The rate of exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) in the state is almost 20% lesser than the all the India average (54.9%) and ranges from 10.4% in the South Garo hills to 45% in the East Garo hills. Among nutrition outcomes in the state, anaemia (among women of reproductive age) is the only indicator that has worsened over the last 10 years.

Figure 1: Trends in key nutrition outcomes in Meghalaya

Source: NFHS 4

Source: NFHS 4

In order to achieve further progress in nutrition, there needs to be an increased focus on improving coverage of interventions targeting the first 1000 days. An increase in the percentage of women receiving antenatal care (ANC) can play a vital role in reducing maternal and child morbidity. At present, only 53% women receive ANC during their first trimester. In fact, the NFHS 4 report suggests that women who receive antenatal care are more likely to give birth in a medical institution under the supervision of a health personnel. Severe efforts need to be made by the state to improve the low coverage of folic acid consumption as well as supplementary food for expecting mothers. This would require an increase in the health workforce as well as focus on rural areas.

According to data from the NFHS 4, the percentage of institutional births — a crucial parameter for access to healthcare services — improved from 29% in 2005 to 51.4% in 2016. Yet, the state lags behind the national average by 27.5%. The percentage of institutional deliveries in rural Meghalaya is almost half of in urban areas. Meghalaya is the second worst performing state in terms of institutional deliveries in the entire north eastern region, according to the ‘Healthy States, Progressive India’ report by the NITI Aayog. Similarly, the percentage of assisted births (by a doctor/nurse/LVH/ANM/other health professional) was as high as 90.8% in the urban areas and 48.1% in the rural areas of the state. Differences within the state range from 89% in the South Garo Hills district to 40.8% in the West Khasi hills district.

Only 9% children received a health check within two days of birth (from a doc/nurse/LHV/ANM/midwife/other health personnel) and 47.5% mothers received post natal care (from doc/nurse/LHV/ANM/midwife/other health personnel) within two days of delivery — way below the national averages. The numbers are far worse in rural areas than in the urban and point to poor health infrastructure and lack of manpower in the rural parts of the state.

Presently, there is a high proportion of vacant positions (35.7%) for medical officers at Primary Healthcare Centres (PHCs) and (31%) nurses at PHCs and Community Health Centres (CHCs) in the state. Reports suggest that very little has been done by the state to address the vacancies. Data from Health Management Information System (HMIS) shows that the number of surgeons required at CHCs is 27 and there is a shortfall of 27 surgeons. Similarly, there is a shortfall of 95 total specialists at the CHCs out of a total 108 required specialists. The number of PHCs have been stagnant at 109 since 2007 and the number of CHCs dropped from 29 in (2007-2012) to 27 in (2012-2017).

The state government must address poor health infrastructure as well as the shortage of health professions, especially since the public health sector is the main source of healthcare in the state (for over three-fourths of households), including for 83% of rural households. Reports also suggest that household members are most likely to visit CHCs and PHCs than government hospitals and thus the government needs to ensure that CHCs and PHCs are well staffed and equipped to provide the necessary care.

While this may seem like a straightforward task, Meghalaya has its own unique challenges that must be recognised too. The state has very poor connectivity, caused by uneven landscape and forests — only 34% of the state is connected by roads — insurgency and terrorism, border disputes with neighbouring Assam and Bangladesh, as well as internal unrest due to demand for a separate statehood. These issues impede the smooth functioning and implementation of the healthcare services in the state.

The challenge for the next state government therefore will be to find innovative and implementable healthcare delivery solutions, despite pre-existing hurdles, focusing specifically on rural and remote parts of the state.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Priyanka is the Communications and Events Officer for the Local Government Revenue Initiative (LoGRI). She is responsible for developing the initiative’s engagement with external stakeholders ...

Read More +

Aaditeshwar Seth Professor Indian Institute of Technology Delhi and Co-founder Gram Vaani India

Read More +