For a few months, it seemed like Germany was learning the right lessons from Russia’s war on Ukraine.

In July 2023, Germany released its China strategy—a 64-page document attempting to recalibrate ties with its top trading partner, while reducing supply chain vulnerabilities and critical dependencies. The document reflected an overall hardening of German policy towards China with a clear acknowledgement that China had changed.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine resulted in a German awakening, extended to the country’s ties with China as part of its broader Zeitenwende. Gone were the days when Berlin allowed Chinese state-owned companies to acquire substantial stakes in its critical infrastructure such as the Hamburg port terminal. Or so it was assumed.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine resulted in a German awakening, extended to the country’s ties with China as part of its broader Zeitenwende.

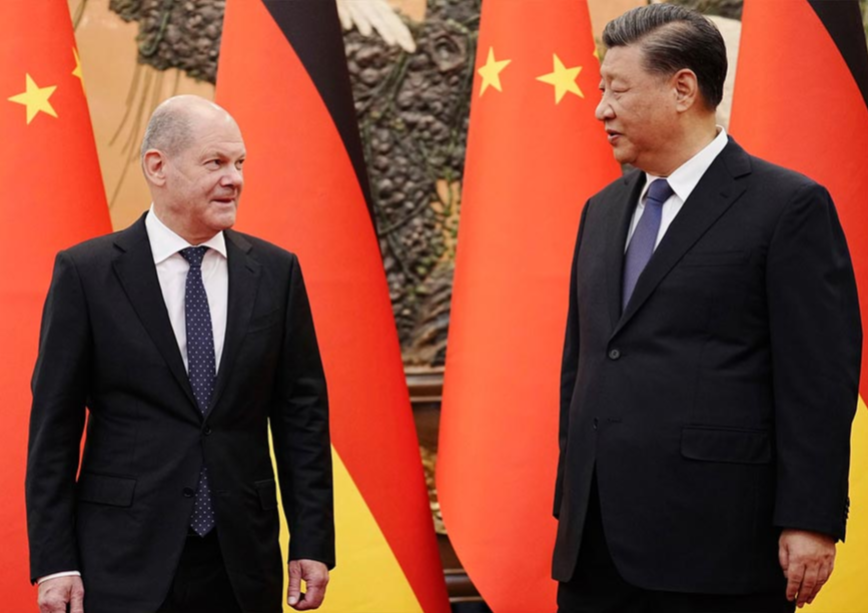

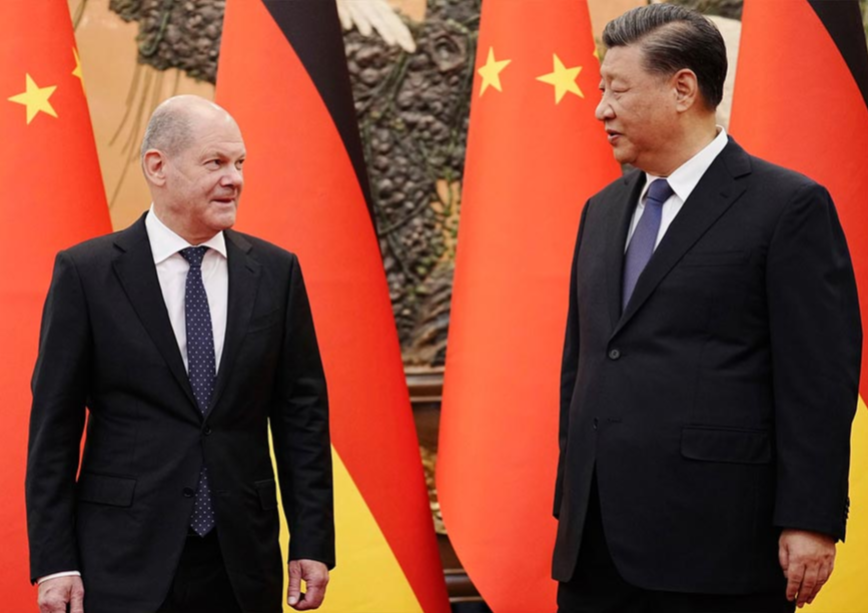

Fast forward to 14 April 2024, and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz is gallivanting across China, visiting Beijing, Shanghai, and Chongqing, accompanied by a high-level representation of three cabinet ministers, and an entourage of powerful German industry executives from Siemens, BMW, Mercedes-Benz, Volkswagen, and Bayer, amongst others.

Scholz’s first visit to China since he assumed office in 2021 took place in November 2022, making him the first Western leader to visit the country after Chinese President Xi Jinping solidified his grip on power, and also the first post-pandemic G7 head of state to do so. His current three-day visit comes at an even more critical juncture with China enabling Russia’s war effort through provisions of dual-use technology and a myriad of EU-China trade tensions.

De-risking or more risking?

The EU’s ballooning trade deficit with China, which stood at €400 billion in 2022, is no secret. Concerns about the Chinese overproduction of goods through state support led to an EU anti-subsidies investigation into China’s electric vehicles industry, flooding European markets and stifling local production. The probe has been widened to include subsidies for other critical green tech such as Chinese solar panels and wind turbines, with medical devices procurement next on the cards. A recently released survey of 150 German businesses operating in China reveals that two-thirds of these companies feel they are facing “unfair competition”, further adding weight to the EU’s calls for improved conditions for European companies in China. And yet, despite the German auto industry facing stiff competition from China’s cheaper imports, fears of Chinese retaliation impacting their exports loom large, given the wider context of a sluggish German economy where growth shrunk by 0.3 percent in 2023.

Thus, the Chancellor’s balancing act was evident when he called for a level playing field and equitable market access for the 5,000 German companies operating in China through “no dumping, no overproduction, and no violation of intellectual property rights”. Simultaneously, fearful of retaliatory Chinese tariffs hampering German exports, he urged the EU to not act out of “protectionist motives”, straight out of Chinese Commerce Minister Wang Wentao’s playbook that only recently accused the EU of protectionism.

Concerns about the Chinese overproduction of goods through state support led to an EU anti-subsidies investigation into China’s electric vehicles industry, flooding European markets and stifling local production.

Even though Germany-China bilateral trade in 2023, at €250 billion, was reduced by 15.5 percent from 2022, a report by the German Economic Institute reveals that German FDI in China rose to a record €12 billion in 2023. Moreover, Berlin’s dependence on China for imports of key commodities such as chemicals, computers, and raw materials central to the green transition, has not decreased. On the contrary, in areas such as rare earths and pharmaceuticals, its reliance on China has increased, despite an overall 20 percent reduction in Chinese imports in the 2022-2023 period. Thus, if any German de-risking is taking place, its progress seems very slow.

On Huawei, while several European countries phased out the Chinese telecoms giant, the company holds a 59-percent share of Germany’s 5G network. On the other hand hand, German companies such as chemical manufacturer BASF and automaker BMW are setting up new plants in China.

However, despite Germany’s greater dependence on the Chinese market than previously on Russian gas—a dependency it has managed to extract itself from—a report by the Kiel Institute for the World Economy posits that Germany’s economy, comparable to what transpired during the COVID crisis, would shrink by 5 percent in the short term in the event of a major break from China, stabilise in the middle term, and avoid even these costs altogether if the trade was reduced gradually. Thus, for Berlin, lack of political will seems to be the bigger problem.

Berlin’s dependence on China for imports of key commodities such as chemicals, computers, and raw materials central to the green transition, has not decreased.

The trip’s agenda also included persuading Xi to exert his influence on Russian President Putin and broker an end to the war, to which Xi asked the West to not “pour fuel on the fire” through sending weapons. Two years since the war and the signing of the Russia-China no-limits partnership, Berlin’s expectation that China would be a benign International actor and Xi an appropriate envoy of peace, while actively enabling Putin, reeks of naivety.

Back to the Merkel-era

Germany’s renewed coziness with Beijing has wider implications given the broader context of Brussels and Washington’s tensions with China.

Scholz’s trip casts a serious shadow over whether Germany is on board with the EU’s increasingly assertive outlook on China, which has guided and set the tone for the policies of its member states. As the bloc’s economic powerhouse, Germany is fundamental to the success of the EU’s China strategy. A visit blatantly centred around an expansion of business opportunities undermines EU cohesion, and serves as a bleak reminder that the more hawkish and human rights-driven Greens were the main force behind Germany’s China strategy and not Scholz’s Social Democratic Party. Besides the United States (US) being Germany’s second-largest trading partner, Berlin is heavily dependent on American security; the conciliatory images of Scholz and Xi strolling about are unlikely to please the Americans.

However, the uncertainty of transatlantic relations in the event of a potential Trump return to the White House combined with his threats to increase across-the-board tariffs, is seen as an incentive to re-balance trade ties with Beijing. This was evident in the readout from Scholz’s communication with French President Emmanuel Macron before his visit where the two leaders “coordinated to defend a rebalancing of European-Chinese trade relations”. Xi’s upcoming visit to France in May will reveal whether Macron chooses to abide by the Scholz playbook amidst heightening US-China competition.

Unsurprisingly, the visit was well-received in China where Xi, aware of Germany’s role as the weakest link in the Western alliance, hailed German-Chinese cooperation as “an opportunity, not a risk”, in the wake of wider troubles with the EU.

China’s economic slowdown, and its aspired growth target of 5 percent this year, grants the continent some leverage vis-a-vis China given the centrality of the European market for Chinese exports.

Beijing’s recent rhetoric, preempting a Trump return that could prevent Europe from aligning closely with Washington in the future, has aimed at wooing Europe. China’s economic slowdown, and its aspired growth target of 5 percent this year, grants the continent some leverage vis-a-vis China given the centrality of the European market for Chinese exports. Yet the cautious approach adopted by Scholz squandered the opportunity to use this leverage in favour of European interests, instead choosing to re-engage Beijing in favour of German corporate interests. For Beijing and its mastery of playing divide and rule in the EU, the visit has given out the right signals.

Berlin’s kowtowing, compared to the EU’s more assertive strategy, demonstrates how German national policy continues to be at the behest of a handful of the country’s industries. Above all, the pre-eminence of commercial profits in Germany’s China policy, much like the Merkel era, validates the challenges in the EU’s path towards becoming a global strategic actor.

As volatile geopolitical events engulf the globe, the German government is yet to catch up and gaze outside its addictive prosperity bubble.

Shairee Malhotra is an Associate Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV