-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

India’s GDP growth estimates are projected to be slower next year; expanding India’s productivity could help tackle this slowdown

Image Source: Getty

All eyes are on India as it continues to be the fastest-growing major economy, showcasing resilience even amidst global political turmoil and the build-up of strategic tensions. The situation is tense on the home front, as gross domestic product (GDP) growth has slowed down from the spectacular growth of over 8 percent in the previous year. Now, the National Statistical Office’s (NSO) first advanced estimates for GDP project growth for 2024-25 at 6.4 percent, causing an opinion overload about the trajectory of India’s growth. Stakeholders and policymakers should focus on the objective factors that have caused a deviation from the post-pandemic momentum, instead of being adrift in waves of speculation. A deeper inquiry into the national account statistics and its underlying parameters is necessary to find explanatory needles in the haystack.

Stakeholders and policymakers should focus on the objective factors that have caused a deviation from the post-pandemic momentum, instead of being adrift in waves of speculation.

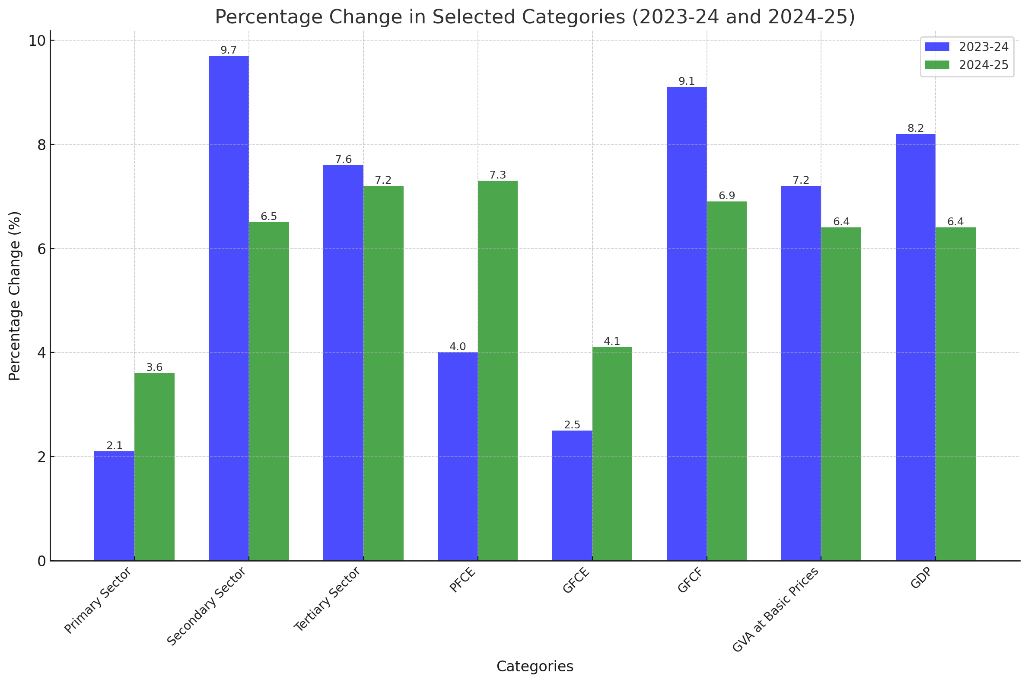

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecasted growth at 7 percent for 2024. Similarly, the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) Monetary Policy Committee projected a 7.1 percent growth in April 2024, and after three consecutive projections of 7.2 percent, abruptly moved down to a 6.6 percent estimate in their December meeting. The revision in growth rate comes not from any real external shock but from expectations of trade volatility, geoeconomic fragmentation, and domestic inadequacies. The cause of this change in perception and forecasts can be understood better through an analysis of the advance estimates. First, the dynamics of aggregate GDP need to be checked. Gross Value Added (GVA) growth is expected to slow down from 7.2 to 6.4 percent, i.e., the actual level of production in the economy is expected to decelerate. However, it should be made clear that this does not entail a reduction in production, rather, it indicates a downshift in the expansion of production since last year.

Figure 1: Percentage change in GDP and components

Source: MoSPI

The more striking observation is that, in nominal terms, the growth rate of GVA has increased from 8.5 to 9.3 percent. Inflation is weighing heavily on the growth of the country. While general inflation (Consumer Price Index) has eased since last year from 5.6 to 4.9 percent, consumer food price inflation has increased substantially from 6.7 to 8.4 percent. In November 2024, the year-on-year food and beverages inflation touched 8.2 percent, driven by inflation of almost 30 percent in vegetables. Persistent inflation has caused the deflator to go up from 1.4 to 3.3, driving a wedge between real and nominal growth. High inflation might partly discount the real growth rate, but it does not assuage worries about a growth slowdown.

An overall expansion in subsidies by over 15 percent for the March-November period has driven apart the GDP and the GVA.

A sharper slowdown in GDP than in GVA growth implies a substantial dip in net taxes (taxes – subsidies), which could be caused either by a contraction in tax revenue or an expansion in subsidies. Gross tax revenue collected till November 2024 is almost 10 percent higher than that collected during the same period of last year. An overall expansion in subsidies by over 15 percent for the March-November period has driven apart the GDP and the GVA. This expansion has been spurred by a 32 percent rise in food subsidies, pushed both by inflation and logistical constraints. Following the withdrawal of the export ban on non-Basmati rice in September, rice that is distributed through the public distribution system (PDS) inflation has soared to 27 percent, due to reinvigorated global demand. Volatile monsoons, leakages from the PDS, insufficient storage facilities, and trade policies have put downward pressure on GDP through high deflators and subsidies.

On the production side, the primary sector expects an upturn, with an increase in growth from 2.1 to 3.6 percent. However, the other sectors paint a gloomy picture with a significant contraction expected in manufacturing and financial, real estate and professional services. The predicament of industrial activity is reflected in the significantly lower production of coal and cement, and the consumption of steel. Further, the Index of Industrial Production (IIP) has declined across mining, manufacturing, electricity, and minerals in the March-October period. The Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI), which is a subjective metric of the health and prospects of a country’s industrial activity, has been on a negative trend across the world, indicating contraction across the emerging and developed world. Despite a lowering of PMI domestically, India has been an exception in the global landscape, maintaining a positive outlook, even in 2024. The slowdown stems from higher production costs, weakening demand, and policy uncertainty in the aftermath of elections across the world.

The services sector estimates are derived from the performance of real sectors, which has resulted in a downward bias due to the dampening of domestic manufacturing by an international slump.

The past performance and current perceptions of the services sector are at odds with the projected contraction of the sector. The Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC) India Services PMI Business Activity Index shows a positive outlook for 2025— supported by buoyant demand, the easing of input prices and new business growth. Services have grown at around 7.4 percent over the last 8 quarters, compared to manufacturing’s 5.6 percent. Services growth is also more stable with significantly lower variance. This implies that the services sector might outperform advance estimates, owing to the dissonance between estimation methods and the prevailing circumstances. The services sector estimates are derived from the performance of real sectors, which has resulted in a downward bias due to the dampening of domestic manufacturing by an international slump.

On the demand front, the strengthening of both private consumption and government expenditure is expected. Till November 2024, only 46.2 percent of the budget estimate has been capital expenditure (capex), almost INR 70,000 crore lower than in the previous year. Owing to the election season, the first half of the year saw significantly lower capex, which could have also discouraged private investment and hampered growth. The anticipated contraction in investment is concerning, although it might be overstated due to its estimation being based on the real assets of construction and machinery. However, the rejuvenation of consumption expenditure, a steady driver of Indian growth, comes as a positive development.

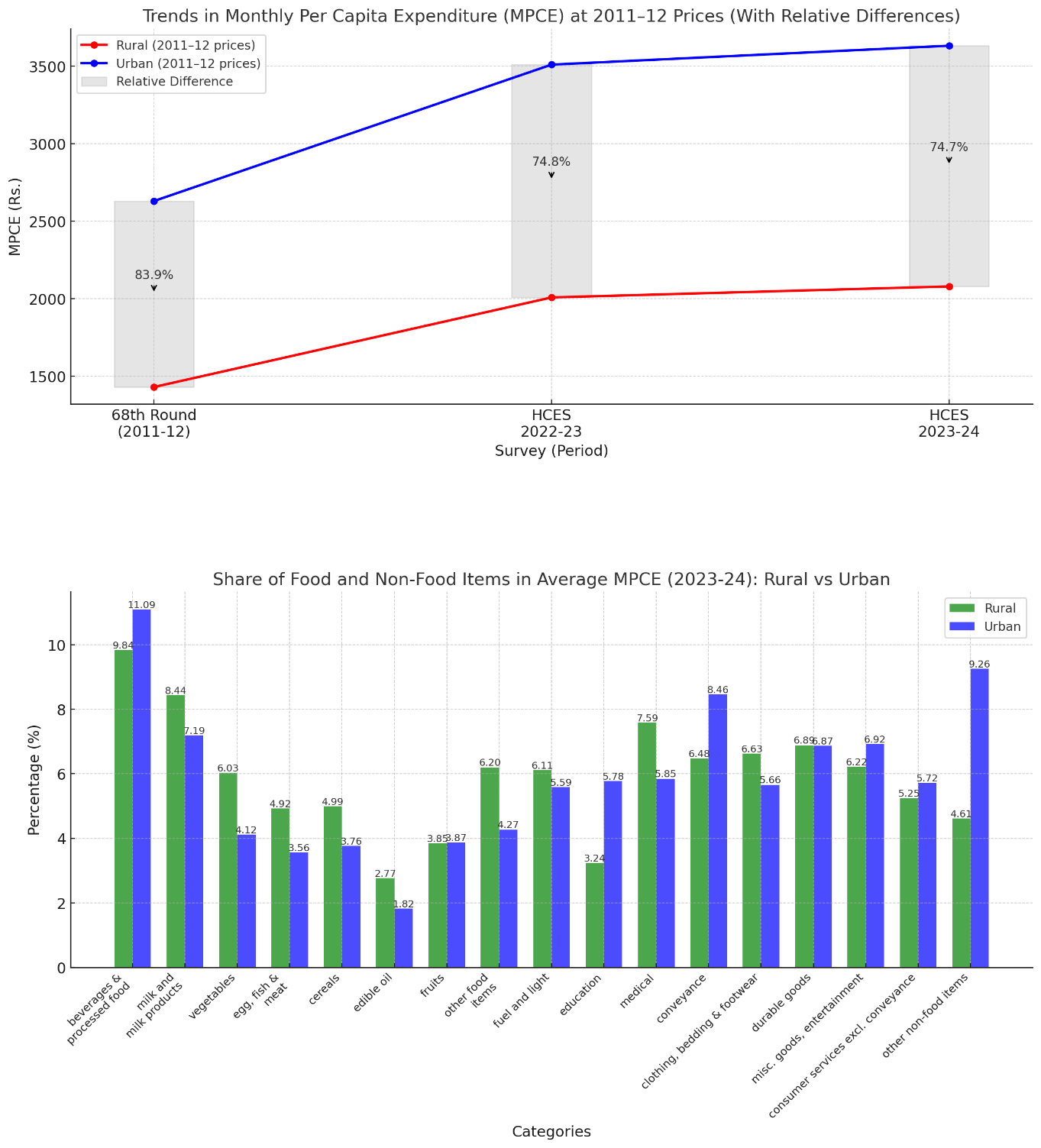

Figure 2: HCES Trends

Source: MoSPI

The Household Consumption Expenditure Survey (HCES) showed around a 3-percent growth in the real monthly consumption expenditure for both rural and urban areas. While the urban-rural divide has remained constant since last year, there has been a significant reduction since 2011-12. However, concern stems from the consumption patterns in the rural areas; the higher share of food items in rural consumption makes them susceptible to the price volatility rampant in the economy now. The silver lining here is that the highest increase in average consumption has taken place for 5-10 percent of the population—a modest feat in alleviating inequality.

The discussion so far has pointed at inflation, increased subsidies, insufficient logistical and infrastructural facilities along the food value chain, the global manufacturing slump, weak government spending and tapering investment as the main culprits deterring India’s growth. Growth above 6 percent should be satisfactory when the global economy is projected to grow at only 3.2 percent; however, to meet the goal of a Viksit Bharat, a significant increase in the growth rate is required. While India’s competition is with itself, domestic growth will have positive reverberations on the global outlook.

India’s demographic dividend will provide waves of workers, but the government needs to intervene to plug them into the production process.

The short-run problem daunting India can be roughly interpreted as stagflation—higher prices and lower output. While a demand boost will enhance output, it will also put greater pressure on price levels and weaken consumption in the absence of a proportionate income adjustment. Consequently, the solution is a long-run measure: productivity expansion. Boosting output through supply expansion will cool down inflation, while also leading to greater consumption demand. Production can be strengthened via an increase in labour, capital, or productivity through advanced technology.

India’s demographic dividend will provide waves of workers, but the government needs to intervene to plug them into the production process. Through the introduction of new initiatives and the expansion of existing ones, education and skills dissemination must be intensified. This will upgrade the effective labour in the economy, directly stimulating production. Similarly, increased capex will drive private investment, boost capital, and carry growth. While abrupt measures can temporarily elevate growth, policy continuity, like in the case of subsidies this year, fosters inclusive and more sustainable growth. Medium to long-run policies, which address the systemic complexities, are needed to put India on the trajectory of high-income levels by 2047 towards a Viksit Bharat.

Arya Roy Bardhan is a Research Assistant with the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Arya Roy Bardhan is a Research Assistant at the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy, Observer Research Foundation. His research interests lie in the fields of ...

Read More +