-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

More research is needed to understand the barriers that Indian companies are facing in China.

Rated as high as 8.9/10 on the Chinese IMDB ‘Douban’ <豆瓣> the movie ‘I am not a Medicine God’【我不是药神】(‘Dying to Survive’ in English) is becoming increasingly popular in China. The movie is based on the true story of a Chinese man who purchased low-cost cancer medicine from India to save the lives of people who cannot pay the high price of the same medicine in China. It follows a man named Cheng Yong, whose rural medical store business is not going well when he suddenly finds this opportunity to smuggle low-cost generic cancer medicine from India on request of a cancer patient (Lu ShouYi). In the process of helping Lu ShouYi, the protagonist not only becomes an agent of Indian generics in China but also discovers the lives of many cancer patients and their families. The story of these cancer patients has moved the hearts of millions of Chinese after a month since the launch of the movie and has led to serious debate surrounding medicine prices in China.

China has gone through a cycle of reforms since its formation in 1950. After three decades of exceptional improvements in health outcomes between 1950-1980, the country went for reform and opening up. In the healthcare sector, the reforms translated into the breakdown of the rural insurance system based on communes and linking of salaries of medical personnel with drug sale markups and user fees. This pushed the healthcare system, especially in the rural areas into a crisis as drug prices skyrocketed and out of pocket expenditure (OOP) rose. Even the National Survey on Social Harmony and Stability conducted by the Chinese Academy of Social Science in 2006, identified ‘high medical expenses’ as the most important concern. As a result, China announced critical health care reforms in the past decade, with the short-term aim of reducing healthcare costs and the long-term aim of improving the quality of care.

After three decades of exceptional improvements in health outcomes between 1950-1980, China went for reform and opening up. In the healthcare sector, the reforms translated into the breakdown of the rural insurance system based on communes and linking of salaries of medical personnel with drug sale markups and user fees.

In 2009, the government came out with a new set of healthcare reforms and promised a sum of USD 125 billion to be spent in the next three years. In this reform, the critical component relating to drug prices was the Essential Drug List (EDL), in which the government lists around 500 frequently used drugs, which are mandatory for community health centres to stock and are sold at zero mark-ups. However, this has not eased the upward pressure on drug prices in China. This could be because of multiple reasons. Firstly, unlike India, China does not have the same platform for generic medicine manufacturers to compete because of its stringent patent laws. In India, this keeps competition high among drug manufacturers as entry barriers are lower and leads to lower drug prices compared to China. Moreover, even among generic medicines, the market leaders are branded generics and not the unbranded ones. The second reason could be the nature of public bidding of drugs in China, which gives preference to original brands even in the case of off-patented products, rather than generics. This is highly paradoxical for a country which spends around 40% of the total health expenditure on medicine (India spends 26%) and people are literally stabbing doctors out of frustration.

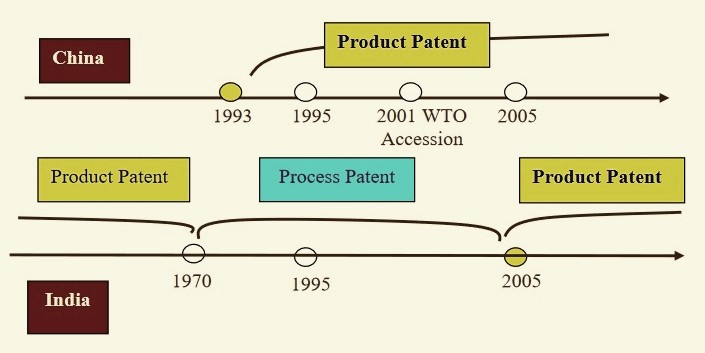

The curious case of the China’s communist government protecting (or preferring to) patented products while India’s mixed economy didn’t, is interesting. China introduced product patenting in 1993, even before the TRIPS standard was introduced in 1995. In comparison, India had abolished product patenting in 1970, which was implemented by the British and introduced process patenting, which allowed domestic companies to manufacture same drugs if they could do it using a new innovative process. This allowed India to keep drugs available and affordable while fostering innovation at the same time. In 2014, the top-5 companies in terms of market share in China were all foreign MNCs (Pfizer, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Sanofi-Aventis and Roche), compared to domestic companies that lead the race in India.

Comparison of Indian and Chinese Patent Regimes. Source: Li 2008

Comparison of Indian and Chinese Patent Regimes. Source: Li 2008

However, because of India’s historically heavy reliance on China for active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), the pharmaceutical trade balance has always been in China’s favour. For instance, in the year 2016-17, India exported around 23.23 million USD worth of drug formulations and biologics to China, while its import figures were a whopping USD 128.63 million. So what can be done to help patients like Lu ShouYi?

There are a couple of things that we can start with. First of all, clearly, drug prices are higher in China compared to India. So China can reduce its healthcare costs by importing drugs from India. More research is needed to understand the barriers that Indian companies are facing in China. Second, it can be deduced from China’s case that the TRIPS agreement has not helped China in developing its domestic pharmaceutical companies and the product patent regime has led to MNCs dominating the market. Third, even in India, the recent introduction of TRIPS has led to MNCs constantly challenging generic Indian manufacturers and starting to enjoy higher profits on their patented products. Therefore, there is a need for dialogue on how developing countries should design their pharmaceutical industry policy to ensure supply of basic medicines to its people.

Solving the above issues will help in reducing India’s trade imbalance and China’s high healthcare costs while providing important policy lessons for other developing countries — a true ‘win-win’ situation!

Hopefully, super hit movies such as these will re-ignite the dialogue on such important issues between the two countries and lead to positive policy changes.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Mohnish is pursuing his PhD at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy (LKYSPP), National University of Singapore. He is theoretically interested in policy ...

Read More +