-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The urgency of SDG financing is unquestionable, but impactful measures to bridge the finance gap have to be designed and implemented

As we cross the halfway mark for the Sustainable Development Agenda 2030, there is still a lot to be achieved in terms of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially since progress towards multiple development objectives has been deterred by the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia-Ukraine conflict, and looming macroeconomic tensions across the globe. Mobilising funds for the SDGs stands critical at this juncture as the financing gap stands exorbitantly around US$ 3.3–4.5 trillion annually. Exploring various channels for actionable policies is imperative, as highlighted by the five avenues analysed below.

Mobilising funds for the SDGs stands critical at this juncture as the financing gap stands exorbitantly around US$ 3.3–4.5 trillion annually.

South-South cooperation, based on shared experiences, existing capacities, and resource constraints, must be complemented with North-South alliances. Global economic disparities often result from Multinational Corporations (MNCs) in the Global North exploiting resources and labour in the South without considering local environmental and social impacts. Such cooperation fosters mutually beneficial alliances between countries, allowing greater participation from Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and Small Island Developing States (SIDs) in global governance frameworks. The United Nations Office for South-South Cooperation envisions such partnerships to facilitate development finance and transform knowledge production, policy design, and funding for achieving the SDGs. Additionally, the priorities of multilateral development banks, often shaped by Global North shareholders, need to align with the needs of recipient countries for meaningful progress.

The public finance of a country is usually subject to pressures of a debt burden, macroeconomic stress and external interest payment. Despite the stretched-out condition of the various government funds, domestic spending must contribute the most significant share for adopting the SDGs. Two main approaches can be taken in domestic fiscal measures to achieve the SDGs. The first involves mobilising domestic resources dedicated to SDGs, which entails fiscal reforms such as strengthening tax administration, reducing tax evasion, and rationalising expenditures. The second approach focuses on developing fiscal policies that discourage industries with a negative impact on SDGs while encouraging those with positive impacts. For instance, this could involve subsidising energy reforms and taxing the use of fossil fuels.

Despite the stretched-out condition of the various government funds, domestic spending must contribute the most significant share for adopting the SDGs.

While, Official Development Assistance (ODA) should primarily target the most vulnerable communities in low- and middle-income countries, high-performing developing economies like India should plan to secure SDG funds from their domestic economy by integrating the SDGs into annual budgets. Each department would be responsible for specific SDG targets, allowing for monitoring and evaluating SDG implementation. The conventional fiscal measures might not be completely effective as orthodox economics was not developed at a time when sustainability was the primary concern. This necessitates using micro and macro-level data and implementing data-supported measures to facilitate policy efficiency, especially in the Global South.

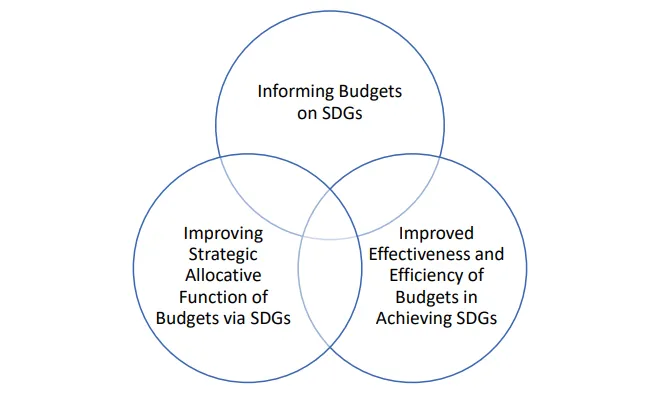

Figure 1: Three Pillars of SDG-Integrated Budgeting

Source: UNESCAP

Source: UNESCAP

SDG financing is essential to encourage firms to adopt the Creation of Shared Values (CSV) model, which promotes the idea that ‘doing well’ and ‘doing good'’ are not mutually exclusive. By incentivising firms to improve their competitiveness while contributing to the social well-being of communities where they operate, the CSV approach ensures financial sustainability, self-reliance, and scalability in achieving the SDGs. Unlike the narrower scope of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), CSV provides a more comprehensive and impactful framework for financing SDG-related initiatives. Firms can support the CSV model through various actions, including redesigning products to serve societal needs, transforming resource use and energy sources in value chain productivity, and fostering local cluster development through skill-based capacity building. International brands such as Adidas, BMW, and Heinz are already adopting initiatives to inculcate the shared value culture.

Figure 2: Creation of Shared Value

Source: Harvard Business School

Source: Harvard Business School

Social entrepreneurship is another avenue for creating social value while maintaining profitability. On a global scale, SDG-aligned businesses offer significant market opportunities worth at least US$ 12 trillion. To further boost SDG financing, governments can consider creating an SDG credits framework, allowing investment managers to build balanced credit portfolios across various social entrepreneurship sectors. These tradeable SDG credits would incentivise investments in companies with positive impacts on the SDGs while enabling firms with significant developmental footprints to sell credits to others with low or negative impacts. Enabling such a credit mechanism would help create a robust market for financing SDG-related projects.

Moreover, capacity-building is crucial to achieving the SDGs, complementing SDG financing through the CSV model and social entrepreneurship. It involves equipping nations and communities with the necessary knowledge and resources to manage transitions and vulnerabilities, facilitating the integration of Agenda 2030 into their national sustainable development frameworks.

The current levels of climate adaptation financing are significantly inadequate to meet the requirements for countries to address the impacts of climate change effectively. Estimated annual adaptation needs for the coming decade range from US$ 160 billion to US$ 340 billion, with projections suggesting that this amount could escalate to US$ 565 billion by 2050. Adaptation finance mainly focuses on holding high-income countries accountable for fulfilling their commitments, emphasising the necessity of allocating a larger proportion of mobilised capital towards adaptation efforts rather than solely investing in mitigation initiatives.

It involves equipping nations and communities with the necessary knowledge and resources to manage transitions and vulnerabilities, facilitating the integration of Agenda 2030 into their national sustainable development frameworks.

The Global South heavily relies on adaptation as a significant part of its climate financing solutions, yet there is a noticeable lack of funding for adaptation projects. One underlying issue pertains to the “economic rate of return” on these projects, which often fails to reflect their overall high “social rate of return.” To address this discrepancy, governments must bridge the gaps through fiscal instruments, such as encouraging public expenditure or offering incentives for adaptation projects. This could be achieved through direct transfers, subsidies, or tax rebates to support and bolster climate adaptation efforts.

SDG financing has experienced significant growth, with sustainability-related investments reaching US$3.2 trillion in 2020, including sustainable funds, green bonds, social bonds, and mixed-sustainability bonds. The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly triggered the rise in SDG funds, particularly health-related funds. To ensure sustained and well-distributed inflow to SDG funds, it is crucial to view them as a continuous effort, considering the integrated and indivisible nature of the SDGs. As fixed-income financial instruments that exclusively finance the SDGs, Sustainability Bonds should be encouraged by global and domestic economies. However, households and the private sector often favour higher-return financial products, while SDG projects may have lower economic returns. Additionally, exploring innovative derivative instruments such as weather derivatives or green infrastructure indices can also help assess the impacts of specific SDGs.

SDG financing has experienced significant growth, with sustainability-related investments reaching US$3.2 trillion in 2020, including sustainable funds, green bonds, social bonds, and mixed-sustainability bonds.

Considering the vulnerability of developing economies and LDCs to global economic shocks, establishing a Development Finance Institution (DFI) under multilateral forums such as the G20 can be considered. The DFI's objective would be twofold: bridging the SDG financing gap by mobilising funds from various sources, directing them to the Global South, and supporting the vulnerable regions during economic crises.

Finally, the urgency of SDG financing is unquestionable, but impactful measures to bridge the finance gap have to be designed and implemented. The methods discussed above provide a bird's-eye view of possible solutions—it is now the implementation question that the policymaking institutions must answer.

Soumya Bhowmick is an Associate Fellow with the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy at Observer Research Foundation.

Arya Roy Bardhan is a research intern at Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Soumya Bhowmick is a Fellow and Lead, World Economies and Sustainability at the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy (CNED) at Observer Research Foundation (ORF). He ...

Read More +

Arya Roy Bardhan is a Research Assistant at the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy, Observer Research Foundation. His research interests lie in the fields of ...

Read More +