-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

India’s water-intensive exports fuel trade gains but heighten regional pressures, challenging sustainability and cross-border water governance.

This article is a part of the essay series: World Water Week 2025

Although water in South Asia is inherently transboundary—flowing across political borders through shared river basins and aquifers—it has rarely been a central consideration in the region’s trade decisions. Historically, trade has been shaped by land, labour, capital, and geopolitical relationships, with water largely invisible in economic negotiations. This omission is striking given that around 90 percent of total water consumption is tied to ‘big water’—the water embedded in food production—compared to the relatively small volumes of ‘small water’ that is used for direct daily needs. For instance, while a glass of water represents ‘small water’, a glass of milk reflects ‘big water’ because of the large volumes required for its production, illustrating the concept of virtual water (VW)—the hidden water embedded in traded goods and services.

While a glass of water represents ‘small water’, a glass of milk reflects ‘big water’ because of the large volumes required for its production, illustrating the concept of virtual water (VW)—the hidden water embedded in traded goods and services.

When agricultural commodities are traded, the water used in their production effectively crosses borders along with the goods, creating a ‘virtual’ outflow of water resources even when trade yields economic gains. In South Asia, this has direct implications for shared river basins and aquifers. Trade within the region keeps virtual water flows inside the basin, potentially supporting regional water security. However, when countries export heavily to the Rest of the World (RoW), they collectively draw from the same transboundary water sources to meet external demand, increasing stress on shared freshwater systems and undermining long-term basin sustainability.

Against this backdrop, this study examines India’s role in the global and regional virtual water trade (VWT) from 1990 to 2023, comparing flows with the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) countries and the Rest of the World (RoW). This comparison highlights how trade destinations shape water stress and cooperation potential in shared basins. By quantifying virtual water exports (VWE) and imports (VWI) for agricultural goods in these two contexts, the study identifies patterns of dependency and their implications for domestic water sustainability and regional water governance. With this, the question arises: In the face of climate change and rising geopolitical uncertainties, can virtual water trade serve as an economic tool for strengthening transboundary cooperation in South Asia?

In the face of climate change and rising geopolitical uncertainties, can virtual water trade serve as an economic tool for strengthening transboundary cooperation in South Asia?

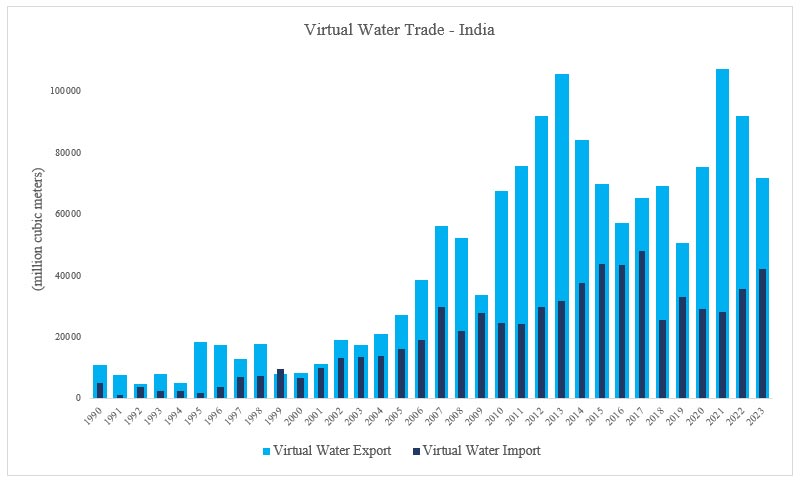

Figure 1 illustrates India’s VWE and VWI from 1990 to 2023. Both have risen sharply over the last three decades. However, VWE have consistently outpaced VWI—meaning India has been exporting far more water, embedded in agri-traded goods, than it imports. In practical terms, these exports represent freshwater resources physically leaving the country through trade. The only exception was 1999, when imports briefly exceeded exports, resulting in a negative VW trade balance of 1,689 million cubic metres (mcm). The average VWE surged from 10,741 mcm in 1990–2000 to 78,302 mcm in 2011–2023, with peaks around 2013 and 2022. In contrast, VWI grew more gradually and remained much lower. This widening gap not only positions India as a major net exporter of water through trade but also raises concerns about long-term domestic water sustainability and security.

Figure 1 : VWT flows from India

Source: Authors’ compilations

Disaggregating these flows into SAARC and RoW markets reveals where India’s exported water is going. Over 1990–2023, India’s average VWE to RoW rose from 9,048 mcm to 60,853 mcm, while SAARC exports grew from 1,693 mcm to 17,449 mcm. Although both markets expanded, RoW consistently absorbed the larger share of India’s exported water. Of India’s total VWE between 1990-2023, 79 percent was exported to RoW as compared to 21 percent to SAARC. Imports also increased for both groups, but export growth far outstripped imports, producing large net VW trade surpluses: for SAARC, from 1,450 mcm in the 1990s to 17,199 mcm in the latest decade; for RoW, from 4,359 mcm to 35,463 mcm. This confirms that India’s water-intensive agricultural output underpins both regional and global supply chains—yet RoW benefits disproportionately in volume and diversity.

In practical terms, these exports represent freshwater resources physically leaving the country through trade.

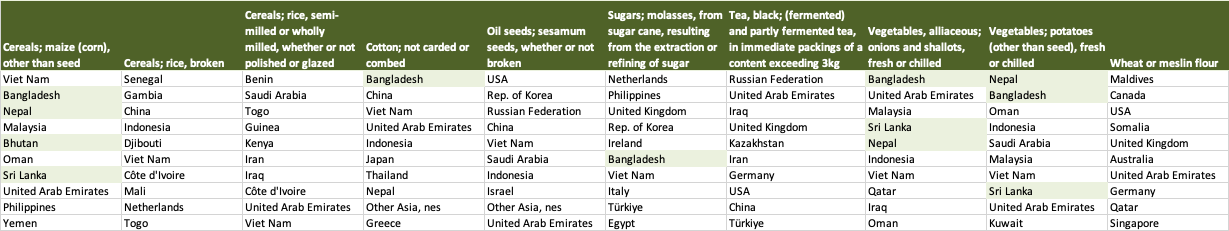

A closer look at India’s trade flows reveals a clear divergence between exports to SAARC economies and to the Rest of the World (RoW). As shown in Table 1, India’s agricultural exports to SAARC in 2023 are heavily concentrated in essential food staples—such as rice, maize, vegetables, and potatoes—serving neighbouring countries such as Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka and directly contributing to their food and water security. These flows are regionally concentrated, relatively stable over time, and shaped by geographic proximity, shared river basins, and historical ties. However, despite SAARC comprising multiple member states, India’s VWE in the region is overwhelmingly limited to just three partners—Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka—which raises concerns about the inclusivity and resilience of intra-regional trade. Overall, in 2023 only 13.9 percent of India’s total VWE was exported to SAARC. In contrast, India’s exports to the RoW (86.1 percent share in India’s total VWE in 2023) are more diversified and globally distributed, comprising high-value, processed, and water-intensive commodities—including tea, cotton, oilseeds, and wheat flour—destined for markets in the Middle East, Europe, North America, and Southeast Asia. While SAARC trade reflects regional interdependence in staples that are vital for shared resource security, India’s engagement with the RoW reflects a commercially driven strategy, enabling integration into multiple global value chains but placing greater cumulative pressure on common freshwater resources.

Table 1: India's top export destinations for selected commodities (2023)

Source: Authors’ compilation using data from UNComtrade

This study set out to examine India’s role in the global and regional VWT from 1990 to 2023, comparing flows with SAARC countries and RoW. The comparison was designed to highlight how trade destinations influence both domestic water sustainability and the potential for cooperation over shared transboundary resources. By quantifying VWE and VWI in these two contexts, patterns of dependency that directly connect to the prospects for regional water governance are identified.

India has emerged as a major net exporter of virtual water, with the majority of exports—especially of high-water-footprint commodities—flowing to non-regional markets.

The results reveal a striking imbalance: India has emerged as a major net exporter of virtual water, with the majority of exports—especially of high-water-footprint commodities—flowing to non-regional markets. While trade with SAARC is dominated by staple foods such as rice, maize, vegetables, and potatoes, these flows are concentrated primarily in Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka, leaving other South Asian countries less engaged. In contrast, exports to the RoW are more diverse, higher in value, and distributed across multiple global markets. This effectively channels significant volumes of shared freshwater out of the region, reducing the availability of water for agriculture, domestic use, and ecological needs across interconnected basins. The pattern signals not only India’s deep integration into global value chains but also a missed opportunity to leverage trade as a tool for regional water cooperation.

South Asia’s geography makes these patterns critical. Major rivers and aquifers—the Indus, Ganges, Brahmaputra, Meghna—are inherently transboundary, and their overuse in one country affects the availability of water across borders. India’s position as both an upper and lower riparian state heightens the stakes, as water withdrawals to sustain agricultural exports can directly impact basin-level water balance and food security for multiple neighbours. Yet existing water treaties are limited in scope, outdated, and increasingly strained by climate change, population pressures, and the shifting dynamics of hydropolitics. The absence of a regional platform for open dialogue reinforces mistrust, and power asymmetries often turn water negotiations into contentious political exercises.

These findings reinforce the study’s central argument: water—particularly virtual water—remains largely invisible in trade decision-making, despite its criticality in regional sustainability. Integrating virtual water accounting into trade policy could transform this reality. By explicitly considering the water embedded in traded goods, South Asian economies could align trade incentives with sustainable basin management. This would not only safeguard domestic water security but also position trade as an entry point for cooperative transboundary water governance—potentially easing political tensions and creating shared economic and ecological benefits.

Major rivers and aquifers—the Indus, Ganges, Brahmaputra, Meghna—are inherently transboundary, and their overuse in one country affects the availability of water across borders.

In conclusion, reframing trade to place virtual water at its core offers South Asia a strategic pathway to address the twin challenges of economic integration and shared resource stewardship. In a climate-constrained and geopolitically complex future, such an approach could shift the region from reactive, treaty-bound water management toward proactive, trade-linked cooperation that benefits all riparian states.

Note: For the analysis, the top 10 agricultural commodities for both export and import have been considered(oil trade was excluded). All calculations and analyses of VWE, VWI, and VW trade balance are the authors’ own compilations using trade data from UNcomtrade and WF values sourced from Mekonnen and Hoekstra.

Mimika Mukherjee is a PhD scholar at the Indian Institute of Technology, Guwahati.

Dr. Anamika Barua is a professor at the Indian Institute of Technology, Guwahati

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Mimika Mukherjee is a PhD scholar at the Indian Institute of Technology, Guwahati. ...

Read More +

Dr. Anamika Barua is a professor at the Indian Institute of Technology, Guwahati ...

Read More +