On 6 April 2022, American cybersecurity firm, Recorded Future

revealed that Chinese state-sponsored hackers had targeted India’s power grids in Ladakh. A part of China’s cyber espionage campaign, the sustained targeting of the power grids was possibly aimed at collecting information on India’s critical infrastructure

<1> or preparing for their sabotage in the future. What technical information the hackers had collected through this breach remains unknown. However, this targeting of the power grids and cyber-espionage campaign fits in the broader pattern of China’s systematic pursuit of offensive cyber operations against India for more than a decade.

India is not alone. Several countries, including the

Netherlands,

United Kingdom,

Australia, and the

United States, and businesses like

Vodafone and

Microsoft have revealed China’s unabated campaign to steal trade and other sensitive data.

The group exploited Microsoft’s email software vulnerabilities to target US government departments, defence contractors, policy think tanks, and infectious disease researchers, amongst others.

China’s cyber espionage against its adversaries

The US Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, for instance, in its

overview of China’s cyber activities, has noted that Beijing conducts extensive hacking operations globally, targeting the health and telecom sector, critical infrastructure providers, and enterprise software providers, stealing intellectual property and confidential information. These targets

provide valuable leads for subsequent “intelligence collection, attack, or influence operations”. The biggest and most recent such hack for cyber-espionage purpose was the breach of the Microsoft Exchange Server by the

Hafnium state-sponsored hacking group in March 2021. The group exploited Microsoft’s email software vulnerabilities to target US government departments, defence contractors, policy think tanks, and infectious disease researchers, amongst others.

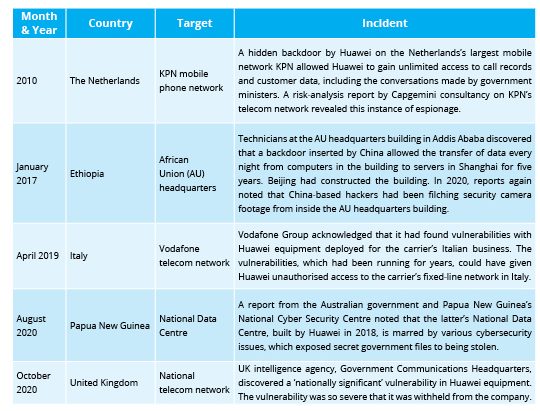

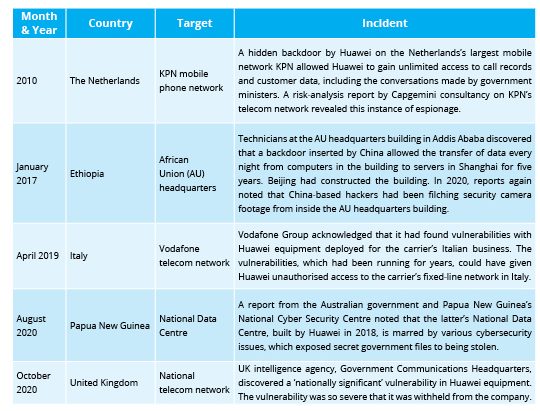

Not just cyber attacks, China has even utilised overseas business contracts and activities to pursue its cyber-espionage campaign. A crucial part of this campaign is the telecom network and fibre optic communications infrastructure provided by Chinese companies like China Telecom, Huawei, and ZTE. The litany of spying instances involving Chinese companies, mostly Huawei, as listed in Table 1, establishes this trend. No wonder, for a long time, policymakers in the United States had been warning and recommending to exclude Chinese firms such as Huawei and ZTE from any critical communication backbone.

Table 1: Select recent incidents of Chinese cyber-espionage worldwide

Source: Compiled by authors

Source: Compiled by authors

China uses cyber espionage to fulfil several objectives. According to the latest US intelligence community

assessment, these cyber-espionage operations often target those sectors which provide potentially rich “follow-on opportunities for intelligence collection, attack, or influence operations.” China uses information ferreted from these sources i) to boost its domestic manufacturing capabilities, and ii) to produce lower-cost imitations of popular western brands/products and, thereby, attain a competitive advantage.

The example of China’s theft of US’ F-35 stealth fighter aircraft data is

well-documented. But there are many other cases where China has

sought competitive intelligence on the foreign business rivals of Chinese companies in multiple sectors, including defence, technology, oil and energy, automobile, and telecommunications.

Target India

While India has so far not proved such an attractive target for China’s commercial cyber espionage, things may be changing.

In March 2021, a Singapore-based company, CyFirma, revealed that a Chinese state-backed hackers’ group had

targeted the information technology systems of two Indian vaccine makers—Bharat Biotech and the Serum Institute of India (SII). These companies’ vaccines have been the most critical element of India’s national vaccination programme and

vaccine diplomacy. Chinese hackers’ targeting of SII is significant when examining the reach of its vaccine, Oxford-AstraZeneca/Covishield, which is being used in

183 countries, as against almost half-reach of China’s flagship Sinopharm vaccine (used in 90 countries). Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s

description of India as the “pharmacy of the world” vividly brings the country’s comparative advantage over China. Therefore, Chinese hackers may be trying to bridge that gap by targeting the vaccine makers to steal commercially valuable data.

A Singapore-based company, CyFirma, revealed that a Chinese state-backed hackers’ group had targeted the information technology systems of two Indian vaccine makers—Bharat Biotech and the Serum Institute of India (SII).

Therefore, we can expect China to broaden its range of targets for commercial cyber-espionage reasons to include sectors like services where India has a comparative advantage. Another potential target includes India’s start-up innovation ecosystem, where India has barred Chinese investments.

But beyond commercial considerations, China’s cyber-espionage campaigns also demonstrate its coercive tactics.

The targeting of the power grids in Ladakh in the middle of the prolonged border stand-off is clearly aimed at sending a political message and signalling that Beijing can open other non-military fronts in the bilateral security competition. Pertinently, this is the second such attack on India’s power sector by Chinese hackers.

In October 2020, in one of the worst power outages, large parts of Mumbai

witnessed a widespread blackout, which affected suburban train services and hospitals. Months later, Recorded Future noted that a China-linked hacker group, “RedEcho,” had

breached the Indian power sector, which may have caused Mumbai’s power outage—a charge

refuted by a Maharashtra government’s technical audit committee examining the incident. But Recorded Future added that besides the power sector, Chinese hackers also targeted two Indian ports and some parts of the railway infrastructure. Coming in the wake of the violent Galwan Valley clash between the Indian and Chinese militaries in June 2020, this targeting of India’s critical infrastructure suggested a combination of intimidation and retribution.

The targeting of the power grids in Ladakh in the middle of the prolonged border stand-off is clearly aimed at sending a political message and signalling that Beijing can open other non-military fronts in the bilateral security competition.

Moreover, the extent of Chinese persistence in targeting India is shown by the Advanced Persistent Threat 30 (

APT30) vector. This threat actor’s espionage operation ran for a decade before its discovery in 2015. It

harvested information from the Indian computer networks on geopolitical issues relevant to the Chinese Communist Party, such as the India–China border dispute, Indian naval activity in the South China Sea, and India’s relations with its South Asian neighbours.

Conclusion

In responding to this widening Chinese cyber-espionage activity, India is hardening its cyber defences and undertaking its

own offensive cyber operations. But it needs to do more. For one, it needs to start outlining technical evidence to attribute these attacks to Chinese state-sponsored hackers—something which the national security establishment has resisted, even as the technical community in India and abroad has presented that evidence.

New Delhi also needs a dedicated mechanism to monitor these offensive operations. While respective intelligence and security agencies do trace foreign spying campaigns against India, this kind of cyber activity is often treated as a cyber breach or incident, focusing on the target and activity, but without linking it to the broader Chinese cyber-espionage campaign, the involvement of state-sponsored hacking groups and the trends in their targeting of Indian computer networks. Perhaps the Defence Cyber Agency can take the initiative to collaborate with the civilian technical community to track these operations. This will send a definite message that Beijing’s mischief is not going unnoticed and is being systematically tracked as part of India’s comprehensive cyber posture.

<1> Critical infrastructure is that infrastructure or essential service which is required to be functional at all times, 24x7. This includes telecom networks, air traffic control, traffic signals, nuclear reactors, power plants, pipelines.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

On 6 April 2022, American cybersecurity firm, Recorded Future

On 6 April 2022, American cybersecurity firm, Recorded Future

PREV

PREV