-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

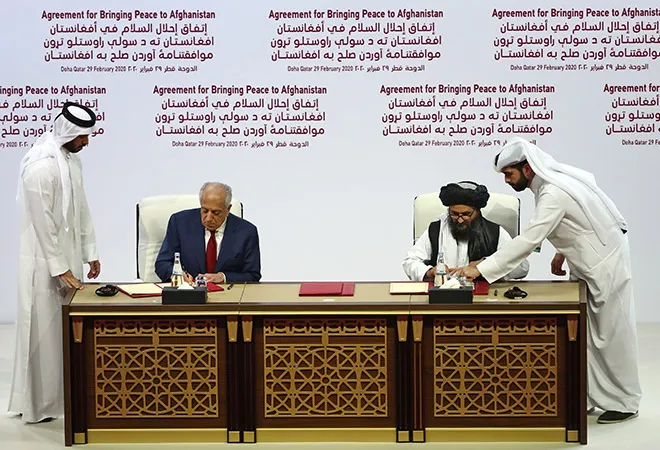

On February 29, 2020, a military solution was finally imposed in Afghanistan. The two agreements signed by the US – one in Kabul with the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (IRA) and the other in Doha, Qatar, with the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA) – to pave the way for a somewhat orderly exit from Afghanistan in just over an year from now, is really nothing more than an acceptance that the Taliban has won this round of the conflict in Afghanistan. The clap-trap about this being a negotiated ‘peace deal’ and the spin being put on what is clearly a ‘withdrawal deal’, one that extricates the US and its allies from Afghanistan and pretty much leaves the Afghans to sort things out between themselves, might serve as a face saver for the US, but the Taliban are calling it what it is, ‘Termination of Occupation’, and declaring victory, quite like their jihadist supporters namely Jaish-e-Mohammad in Pakistan.

With the end-game of the current round of the unending Great Game in Afghanistan now set into motion, all questions about whether Afghanistan was a war worth fighting, or whether it was a winnable war, or even about all the blunders by the Americans that led them to this pass, are quite irrelevant now. The only question worth asking at this stage is whether these “agreements” will deliver in bringing even a modicum of peace to Afghanistan, or will Afghanistan be revisited by the unspeakable brutalities and savagery of the Taliban terror cohort as they make a power grab. And, then there is the single most important question of who will enforce the agreement if the Taliban either renege or violate their side of the bargain.

The agreements itself contain no major surprise. Much of what is there in the agreement with the Taliban had been revealed in dribbles. Only a couple of things weren’t very clear: one, the time-line of withdrawal; and two, whether or not the US will retain any military bases or military presence in Afghanistan. The Taliban agreement has given clarity to both these issues by laying down clear time-lines: intra-Afghan negotiations are to start from March 10; reduction in US troops to 8600 and allied troops proportionally in 135 days, or by July 15; US to vacate 5 bases by the same time; all foreign forces to withdraw and all bases to be vacated in 14 months, or by April 2021; Some 5000 Taliban prisoners and around 1000 prisoners in Taliban custody will be released by March 10, and the rest within three months, or by end May 2020; US will seek removal of UN sanctions on Taliban by May 29; US aims to remove US sanctions on and rewards against Taliban by August 27.

While there are clear time-lines given by the Americans and there is nothing ambiguous about what the US will do to keep its side of the bargain, the Taliban commitments aren’t as watertight. Although the Taliban have undertaken to not allow the use of Afghan soil to threaten the security of the US and its allies, in pursuit of this commitment all that the Taliban are required to do is to “send a clear message” to those posing a threat to US and its allies, and “instruct members” not to cooperate with these elements. Even more troublesome is the clause that will for all practical purposes make Afghanistan a sort of safe haven for all the despicables from around the Islamic world who see Afghanistan as the fulfilment of their jihadist fantasies and have been fighting in that theatre. The Taliban are not supposed to expel these people but are expected to give them asylum so that they “do not pose a threat to the security of the US and its allies.” Alongside, the Taliban is bound to not provide travel documents or assist in any way those who pose a threat to the US and its allies. The Taliban have undertaken that their prisoners will abide by the terms of the agreement and not pose any threat to the US or its allies.

All this is all very well, but if the Taliban don’t adhere to their side of the bargain, what will the US do? Stop withdrawal? Restart operations? Simply put, all the commitments are going to be worth nothing if there isn’t a mechanism to verify and enforce the agreement, and in the event of someone trying to short-circuit the deal, then penalising those people. The Taliban will easily go on the war-path if the US reneges, but will the US do the same if the Taliban renege?

Interestingly, throughout the agreement, every reference to the Taliban is prefixed by “Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan which is not recognized by the United States as a state”, and yet by committing the Taliban to “providing asylum or residence” to people who pose a threat to the US and its allies, and asking them to ensure that no travel documents will be given to these elements (something which is normally a state’s duty), the agreement for all practical purposes accepts the Taliban as the future state of Afghanistan. Although the agreement does mention that “the new post-settlement Afghan Islamic government as determined by the intra-Afghan dialogue”, to commit the Taliban to not give travel documents or to give asylum/refuge pretty much gives the game away. After all, who is travelling on travel documents issued by the Taliban all these years? This is a question that has often been put but never really answered. What travel documents were people toing and froing to Qatar and other locations for talks traveling on? If those weren’t issued by Taliban, which is not recognised by any country (not even by their patrons, Pakistan), then will travel documents issued by Taliban before a post-settlement government is formed be acceptable to any country around the world?

This is problematic also because in the Joint Declaration (JD) signed with the Afghan government it is quite implicit that the US is treating the Taliban as the primary player in the Afghan theatre, and the Afghan government is at best a peripheral, or just one among the other players insofar as actual negotiations for a future political road-map are concerned. At the same time, the Afghan government also has a critical role to play in ensuring that the “agreement for bringing peace” can move forward smoothly. Without the cooperation of the Afghan government, neither the prisoner exchange confidence building measure is deliverable, nor other assurances given by the US is possible.

The Joint Declaration talks about settlement as a result of an intra-Afghan dialogue, but this will be “negotiations between the Taliban and an inclusive negotiating team of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan”. Not between a team of government of IRA or a team chosen by government of IRA, but a team of people from IRA, which could include members of government but they will be not be spearheading the negotiations. This becomes clearer in the Taliban agreement which says “Taliban will start intra-Afghan negotiations with Afghan sides”, not Afghan government, not even ‘led by Afghan government’. For all practical purposes therefore, the Joint Declaration is nothing but a means to get the IRA on board for the agreement with the IEA. What is more, the Afghan government has been severely undermined by reducing it to the level of just another stakeholder and not the principal stakeholder in the negotiations. The JD also has got the support of IRA for a phased withdrawal of US troops, but with the caveat that the Taliban fulfil their commitments. While the US has reaffirmed its security commitments to the IRA and Afghan security forces, it is mainly directed against the al Qaeda, ISIS-Khorasan, and other international terrorist organisations. So much so, for the Afghan-led, Afghan-owned peace process, the tag line that has been parroted for years now.

Both the agreements are “interlinked and interdependent” with each other and are supposed to move in tandem. For instance, the lifting of US sanctions and the removal of Taliban from UN sanctions list is contingent on the start of the intra-Afghan dialogue. The Taliban agreement has listed four inter-related parts of the peace agreement. But, the US-Taliban agreement relates to implementation of only the first two parts – US commitments to withdraw and the Taliban commitments to not allow Afghanistan to become terror central again. Once implemented, these are supposed to pave the way for the other two parts – “intra-Afghan negotiations with Afghan sides”, and a “permanent and comprehensive ceasefire”, the date and implementation mechanism of which will be announced along with “completion and agreement over the future political roadmap of Afghanistan.”

In other words, there is no guarantee that the Doha accord will immediately usher in peace. This means that even as the intra-Afghan negotiations continue (mostly on Taliban terms) the Taliban who have the momentum on their side will keep up their attacks to not only increase their negotiating power but also expand their footprint across the country. What is more, the deal that the US has entered into focusses more on ensuring that Afghanistan is no longer used to threaten the security of US and its allies, and not so much to ensure the security of the Afghans or countries that do not fit the description of US allies. The implication of this for countries like Iran and perhaps even Russia and other regional countries is going to be a matter of some concern.

The intra-Afghan dialogue to pave the way for a “post-settlement Afghan Islamic Government” is going to be the real problem. One, there is time-line of sorts dictating the agenda. The US is committed to completely withdraw all forces by April 2021. In these fourteen months, a political deal has to be worked out. The fact that it took the US Special Envoy Zalmay Khalilzad nearly a year and a half to negotiate a somewhat half-baked ‘peace agreement’, the contours of which had more or less been fixed long back and in which most of the ‘give’ is from the side of the US and Afghan governments and very little ‘give’ from the Taliban side, this should inform everyone of the difficulties in negotiating a political deal between the Afghan government and stakeholders and the Taliban.

Apart from the political complexities involved in the negotiations, jostling for space between different players and the fact that the negotiations will be taking place amidst a war (even if the intensity of this war reduces, which is a very big if), there are just too many moving parts in the entire framework under which the peace talks are going to be held. The inter-linking and interdependence of the various obligations and commitments by all sides is at one level supposed to ensure things move forward smoothly; but at another level, these very same factors will jeopardise the entire process because without one thing happening, the other cannot happen. That all this will happen against the backdrop of a time-line, which is likely to be unwavering because the keenness of the Americans to not delay the final withdrawal much beyond the April 2021 deadline, further adds to the complexity of the situation. While some delays are likely to be inevitable given the nature of the problems, there is a real fear that there will be many hold-outs and hold-ups, not to mention spoilers, to muddy the already murky scene.

The bottom-line is that the ‘peace deal’ is still not quite a done deal. Given the treacherous political and security landscape of Afghanistan, a lot of action is going to happen, both on the battlefields as well as negotiating table. For India, this means that the ball is still very much in the play. And even if by some miracle, the Afghans show remarkable statesmanship and actually seal a deal between themselves, there will be the whole question of how the new Afghan state will sustain itself. Although the Americans have promised to resource the Afghan security forces and seek “economic cooperation for reconstruction” with the new Afghan entity, not many people think this commitment will last more than a year or two even if everything works out exactly how it is being hoped it will. To put it bluntly, pessimism about how things will pan out after this ‘peace deal’ is probably far more in conformity with the natural order of things in Afghanistan than any exuberant expectation that some people may be harbouring.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Sushant Sareen is Senior Fellow at Observer Research Foundation. His published works include: Balochistan: Forgotten War, Forsaken People (Monograph, 2017) Corridor Calculus: China-Pakistan Economic Corridor & China’s comprador ...

Read More +