-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

This article is a chapter in the journal — Raisina Files 2023.

“Even the true home of my heart’s desire, Europe, is lost to me after twice tearing itself suicidally to pieces in fratricidal wars. Against my will, I have witnessed the most terrible defeat of reason and the most savage triumph of brutality in the chronicles of time. Never—and I say so not with pride but with shame—has a generation fallen from such intellectual heights as ours to such moral depths.”

― Stefan Zweig, ‘The World of Yesterday’

AS EUROPE CONTINUES TO grapple with Russia’s ongoing war against Ukraine, the prospect of devastating, cascading effects looms on the horizon.<1> Western military experts assert that Moscow’s multifaceted approach encompasses three distinct yet interconnected dimensions:<2> a military aggression against Ukraine; a war against Western values, norms, and standards; and a non-kinetic war targeting the European economy through the weaponisation of commodities. These interconnected crises represent a significant challenge to the cohesion and unity of the European Union (EU) and its member states, as well as the stability and security of the entire European continent.

The war on Western values threatens EU's internal security order, while the non-kinetic war on the economy puts Europe in a vulnerable position in a vastly changing world.

After almost a year of war, it is time to reflect and assess the events that have transpired in the continent.

Zeitenwende or Status Quo?

The turning point (‘Zeitenwende’)<3> in German foreign and security policy was noted with the speech of Chancellor Olaf Scholz in February 2022, marking an epochal geopolitical change; yet the extent of this shift and its true intentions remain uncertain. The hesitation in addressing the issue of the tank deliveries to Ukraine<4> is only one of many manifestations of Berlin’s lack of willingness<5> to assume a leadership role and guide Europe through these historic changes. Currently, another grave escalation looms on the horizon and a prompt response is imperative as it will determine the outcome of the war.<6> However, the most recent example of the lack of unity—on the possible delivery of military jets to Ukraine—<7> proves yet again the case that Western powers are not on the same geopolitical page.

It is true that Europe has achieved the seemingly impossible in terms of coordination and coherence in responding to the Russian war against Ukraine. Given the typical pace and scope of European decision-making,<8> this is an enormous accomplishment that still stands. The nine sanctions packages alone are a clear statement.<9> The resolve to provide diplomatic, political and humanitarian aid to Ukraine is attributed to the coherence between the EU institutions and states.<10> A lingering aftertaste remains, however, as there were ongoing disagreements between the member states, based on their dependencies on Russian resources, national interests, and internal political dynamics.<11>

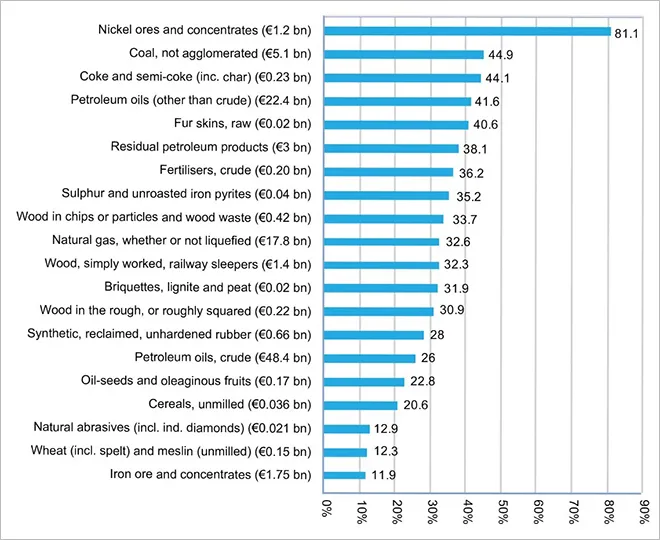

Figure 1. Top 20 EU Commodity Imports from Russia (2021)

Source: European Parliament, Research Service<12>For instance, countries such as Austria, Italy and Germany were affected significantly due to their high dependence on Russian gas supply.<13> Moreover, Hungary has impeded quick decision-making regarding the European sanctions and is currently blocking the sanctions on Russian nuclear energy.<14> At the same time, internal policy dynamics hinders the European decision-making process. The Austrian government,<15> ahead of a highly important provincial election, prevented the long-awaited accession of Bulgaria and Romania to the Schengen for the sake of its domestic political campaign on migration policy.<16> Furthermore, various exceptions<17> had to be made for different sanctions packages, with the member states contributing to the negative dynamic—from dealing with the question of diversifying energy resources,<18> to the expulsion of Russian diplomatic personnel,<19> to the support of certain Russian narratives about the invasion of Ukraine.<20> Domestic factors such as the rise of populist and nationalist movements in Europe could also contribute to European disunity.<21> These movements often have Eurosceptic views and can put pressure on governments to adopt a more nationalistic and less cooperative stance in international affairs, including the war in Ukraine.

Source: European Parliament, Research Service<12>For instance, countries such as Austria, Italy and Germany were affected significantly due to their high dependence on Russian gas supply.<13> Moreover, Hungary has impeded quick decision-making regarding the European sanctions and is currently blocking the sanctions on Russian nuclear energy.<14> At the same time, internal policy dynamics hinders the European decision-making process. The Austrian government,<15> ahead of a highly important provincial election, prevented the long-awaited accession of Bulgaria and Romania to the Schengen for the sake of its domestic political campaign on migration policy.<16> Furthermore, various exceptions<17> had to be made for different sanctions packages, with the member states contributing to the negative dynamic—from dealing with the question of diversifying energy resources,<18> to the expulsion of Russian diplomatic personnel,<19> to the support of certain Russian narratives about the invasion of Ukraine.<20> Domestic factors such as the rise of populist and nationalist movements in Europe could also contribute to European disunity.<21> These movements often have Eurosceptic views and can put pressure on governments to adopt a more nationalistic and less cooperative stance in international affairs, including the war in Ukraine.

The lack of unity among the EU member states has its roots in the historical, diplomatic, geoeconomic and cultural ties of some European powers with Russia. For instance, France and Germany, prior to the beginning of the war were engaging Moscow in a geopolitical rapprochement and normalisation of relations.<22> The lack of coordination among member states has also resulted in some European countries like Austria or Hungary taking their own actions without consulting with the EU.<23> Public opinion in Europe was another dividing line. Even though the people in the Western countries have been mostly supporting Ukraine’s cause, some governments have had to take into account that their citizens are sceptical of getting involved in a military conflict.<24>

In addition to the war in Ukraine, a battle has also been fought against the European rule-based security order, European norms and values, and Europe’s global geoeconomic clout. Russia has failed in most of these endeavours for various reasons. While the instrumentalisation of energy, food and fertiliser supplies by Russia<25> has pushed prices up and brought inflation in Europe to double-digits for the first time in history,<26> Europe has been able to cushion these negative effects through energy savings, filling up storage capacities, and other ad-hoc institutional, political, and economic measures. Furthermore, the historically ‘mild’ winter has played a positive role, tempering energy demand. Ultimately, international efforts and institutional mediation such as the grain initiative between Russia and Ukraine under the mediation of Turkey and the UN, were able to limit some of the negative consequences.<27>

Europe: ‘The World of Yesterday’?

The debate on Europe's strategic autonomy<28> has come to a dead-end since February 24th, when the Ukraine war erupted. If it were not for the United States,<29> which quickly facilitated weapons deliveries and other support since the beginning of the war and thus gave Ukraine the ability to withstand Russia's comprehensive military attacks, Kyiv would have surrendered long ago. This conclusion leads to the realisation that Europe is still unable to manage wars and military confrontations on the old continent on its own and remains dependent on US support. This becomes even clearer with the decision of two neutral states—i.e., Sweden and Finland—to take the radical step and finally apply for membership to NATO. Against this backdrop, a turning point for the European security and defence policy may arise given how the majority of member states are more reliant on the security guarantees of the US and NATO than those of the European Union. The exceptions in this regard are four neutral island states—Malta, Cyprus, Ireland, and Austria, metaphorically referred to as the ‘island of the blessed’. After Sweden and Finland join NATO, there will be serious power shifts, with Poland, the Baltic states, and the Scandinavian states gaining more geopolitical significance. This trend could put into question the German ‘Zeitenwende' despite the goal of spending 100 billion Euro for defence capabilities.<30>

The ongoing situation has brought to the forefront a multitude of crises faced by Europe as a result of Russia's non-kinetic war, including food and energy shortages, migration waves, the threat of nuclear weapons use, and information warfare. Geopolitical pundits have been pointing to the emergence of the ‘permacrisis’,<31> with one problem quickly being replaced by another while European decision-making faces the perpetual challenge of overcoming them. This new phenomenon has supplanted the previous understanding of ‘polycrisis’<32> that points to simultaneous crises in all relevant fields of activity—from finance to neighbourhood policy to security. Although the cascading effects of the permacrisis have been overcome in the short term, the major geoeconomic and geopolitical challenges remain unresolved.

The European powers must find ways to effectively manage the interrelated impacts on the economy, energy supply, political stability, and fiscal policy. The policies of the European Commission designed to save Europe—such as the Next Generation EU,<33> the EU Battery Regulation,<34> the European Chips Act,<35> and the New Green Deal,<36> could be a way to address some of the challenges that Europe is facing and leverage the opportunities. It has become increasingly clear that no single European power can withstand these challenges on their own, and if a comprehensive and sustainable solution is not reached, Europe may find itself relegated to the geopolitical backyard like it did 100 years ago.

Europe’s Bifurcation

In a highly volatile and turbulent year, one cannot but expect crucial systemic shifts and second-order geoeconomic effects from the prolonged pandemic in China as well as Russia’s war of attrition against Ukraine. This year will be a turning point for European security as the global order is facing a process of bifurcation.<37> A pessimistic scenario would imply a more radical and consistent mutual decoupling between the United States and China in which the modus vivendi of coordination between China and Russia (the ‘DragonBear’)<38> in all strategic domains will finally become apparent. Meanwhile, an optimistic scenario reveals a more peaceful systemic co-existence as Beijing would focus on partnerships and commitments to strengthen its domestic development until it builds a credible counterbalance to the overwhelming American influence. In both scenarios, the message is clear: in the long run, every state actor—big or small—will have to choose sides between two very different global systems with their own norms, rules, and ideologies.

Against this background, the West is facing a growing split between the Anglosphere (the US, the UK) and the EU (the Franco-German backbone of the EU) when it comes to dealing with the ‘DragonBear’ (China and Russia) amid the emerging bifurcation of the global order. This, even if China's junior partner, Russia, manages to redraw the geopolitical map of Europe in its favour if it succeeds in its war against Ukraine. The war has created a dangerous cleavage between some of the EU members despite their coherent approach on the sanctions policy towards Russia. Central and Eastern European (CEE) members were compliant with the US position regarding the delivery of heavy weapons to Ukraine, while France and Germany were trying to initiate peace talks with Russia to help the country “save face” amid its military downfalls.<39>

In 2023, two events could exert a significant influence on European security: the NATO membership of Finland and Sweden, and a possible political union between Poland and Ukraine. The Nordic and CEE countries choose the US as a security guarantor instead of the European Union or the Franco-German axis.<40> The political union between Poland and Ukraine could be a geopolitical analogy to the German reunification in the 1990s to ensure Ukraine's rapid accession to the EU and NATO without going through a formal application process. If that happens, the balance of power within Europe will shift eastward and create completely new geopolitical realities in the continent.

Future Outlook

There are three main scenarios for the Ukraine war. In the first scenario, Ukraine receives sufficient heavy weapons systems and ammunition and is able to push back Russian troops from its entire territory, or at least a large part of it. At the same time, Western sanctions could lead to a collapse of the Russian economy or even the dissolution of the Russian Federation in the context of emerging secessionist movements and Russia’s increasing international isolation. In the second scenario, a future is imagined in which due to insufficient and slow deliveries of heavy weapons to Ukraine, a Russian victory in the Donbas region becomes possible. This allows Russia to shift its focus south towards Odesa and continue the war of attrition using additional waves of mobilisation. Finally, the third scenario envisages that Ukraine becomes too slow in acquiring heavy weapons systems, while Russia, despite comprehensive Western sanctions, does not remain internationally isolated, especially due to partners like China, India, Turkey, and Iran. In this scenario, a new ‘frozen conflict’<41> threatens to emerge in the coming years given Vladimir Putin’s ambition to run for the presidency in the March 2024 polls.<42>

So far, Ukraine has not received any security guarantees from the West and must fight for its very existence as a nation and state, while 17 percent of its territory remains under Russian control.<43> The country is in a geopolitical grey zone between the Euro-Atlantic community and Russian imperialism and revisionism. After a year of the most devastating war on the old continent, the situation has become even more dangerous in view of the impending escalation phase. Ceasefire and peace negotiations seem currently unrealistic due to the diametrically opposing goals of the two countries. It remains unclear how the war will end and which scenario will occur. To enable the first scenario, Europe must not only continue but also intensify its military support for Ukraine while credibly diversifying its relationships with third countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America to heighten Russia's isolation.

Vladimir Putin once famously said that the collapse of the Soviet Union was the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century.<44> The Russian president is probably the biggest proponent of the ‘realism’ school and has understood the geopolitics of the 21st century well, but at the same time has failed to prepare his own country, society, and military for it. Thus, he could lead the Russian country from the "greatest geopolitical catastrophe" of the 20th century to a likely final dissolution of the Russian Federation in the 21st century. Eastern European historian Karl Schlögl is convinced that the downfall of the Russian empire is the only condition for Russia's self-discovery, regeneration and survival.<45> Consequently, what is most urgently needed is a strategic consensus within the EU and its member states to not only secure the survival of Ukraine but also enable a real victory for Ukraine against Russia.

<1> T.G. Benton et al., “Cascading Risks From Rising Prices and Supply Disruptions: The Ukraine War and Threats to Food and Energy Security,” Chatham House (2022).

<2> Bundesministerium für Landesverteidigung. (2023). Risikobild 2023: Krieg um Europa.

<3> Deutsche Welle, “’Zeitenwende‘ Amid Ukraine War Named German Word of the Year," December 2, 2021.

<4> Euronews, “Leopard 2: Can Germany's Hesitation Over Ukraine Exports Tank its Reputation and Arms Sales?,” January 25, 2023.

<5> S. Marsh, and A. Rinke, “Analysis: Failure to Communicate? Scholz Thinking on Tanks for Ukraine Perplexes Many Germans,” Reuters, January 24, 2023.

<6> The Guardian, “Russia Begins Major Offensive in Eastern Ukraine, Luhansk Governor Claims,” February 9, 2023.

<7> CNN, “After Getting Tanks, Ukraine Escalates Public Pressure Over F-16 Fighter Jets,” January 31, 2023.

<8> Council of the European Union, “The Decision-Making Process in the Council,” n.d..

<9> Council of the European Union, “EU Restrictive Measures Against Russia Over Ukraine,” n.d..

<10> Council of the European Union, “EU Solidarity with Ukraine,” n.d..

<11> European Parliament, Research Service, “Russia's War on Ukraine: Implications for EU Commodity Imports from Russia,” 2022.

<12> European Parliament, Research Service, “Russia's War on Ukraine: Implications for EU Commodity Imports from Russia”

<13> Clean Energy Wire, “Germany, EU Remain Heavily Dependent on Imported Fossil Fuels,” 2023.

<14> EURACTIV.com and Reuters, “Hungary Will Veto EU Sanctions on Russian Nuclear Energy, Orban Warns,” January 27, 2023.

<15> Jorge Liboreiro, "Schengen: Romania Blasts Austria for 'Inexplicable' Move to Block Access to EU's Passport-Free Zone," Euronews, December 9, 2022.

<16> Suzanne Lynch, "Migration Feud Derails Expansion Plan for Europe’s Schengen Visa-Free Travel Area," Politico, December 7, 2022.

<17> Council of the European Union, “EU Restrictive Measures Against Russia Over Ukraine,” n.d.,

<18> European Commission, "Diversification of Gas Supply Sources and Routes," Energy, European Commission.

<19> Sammy Westfall and Maite Fernández Simon, "Which Countries Have Expelled Russian Diplomats Over Ukraine?" The Washington Post, April 25, 2022.

<20> Dmitry Gorenburg, "Russian Foreign Policy Narratives," Security Insights no. 042, November 2019.

<21> Gentiana Gola and Emily Bloom, "Defining Moments for Democracy in Europe in 2022," The Global State of Democracy, December 22, 2022.

<22> Sabine Fischer, "The End of European Bilateralisms: Germany, France, and Russia," Carnegie Moscow Center, December 12, 2017.

<23> Liik Kadri, "The Old is Dying and the New Cannot Be Born: A Power Audit of EU-Russia Relations," European Council on Foreign Relations, December 14, 2022.

<24> European Parliament, "Public Opinion on the War in Ukraine," January 20, 2023.

<25> Xolisa Phillip, “‘Russia Using Food and Energy as Weapon against Europe and Africa,’ Says Vice-Chancellor Habeck,” The Africa Report, December 8, 2022.

<26> David McHugh, "Inflation in Europe Eases but Still in Painful Double Digits," AP News, November 30, 2022.

<27> "United Nations Black Sea Grain Initiative Joint Coordination Centre," United Nations, n.d..

<28> European Parliament, "EU Strategic Autonomy 2013-2023: From Concept to Capacity," Think Tank Briefing, July 8, 2022.

<29> Jonathan Masters and Will Merrow, "How Much Aid Has the U.S. Sent Ukraine? Here Are Six Charts," Council on Foreign Relations, December 16, 2022.

<30> Holger Hansen, "German Lawmakers Approve 100 Billion Euro Military Revamp," Reuters, June 3, 2022.

<31> Fabian Zuleeg , Janis A. Emmanouilidis and Ricardo Borges de Castro, "Europe in the Age of Permacrisis," European Policy Centre, March 11, 2021.

<32> European Commission, "Speech by President Jean-Claude Juncker at the Annual General Meeting of the Hellenic Federation of Enterprises (SEV), Athens," June 21, 2016.

<33> NextGenerationEU, "NextGenerationEU," Europa.

<34> "EU Battery Regulation Make New Demands on Industry," Stenarecycling.com, February 10, 2023.

<35> European Commission, "European Chips Act," europa.eu, accessed February 10, 2023.

<36> European Commission, "A European Green Deal," Commission.europa.eu, February 10, 2023.

<37> Velina Tchakarova, "Bifurcation of the Global System," in Envisioning Peace in a Time of War: The New School of Multilateralism - Ten Essays, Werther-Pietsch, ed., Ursula, 97-111 (Facultas, 2022).

<38> Velina Tchakarova, "Enter the 'DragonBear': The Russia-China Partnership and What it Means for Geopolitics," ORFonline.org, April 29, 2022.

<39> Judy Dempsey, "Judy Asks: Are France and Germany Wavering on Russia?" Carnegie Europe, December 8, 2022.

<40> "CEE countries (CEECs)," CBS News, January 31, 2018.

<42> “Kremlin Readies for Putin’s 2024 Re-Election Under Shadow of War – Kommersant,” The Moscow Times, January 13, 2023.

<43> Roman Rukomeda, “‘Ukraine Is Concentrating on Winning the War and Reinventing Itself’,” Www.euractiv.com, January 12, 2023.

<44> Claire Bigg, “World: Was Soviet Collapse Last Century’s Worst Geopolitical Catastrophe?” RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, April 29, 2005.

<45> “Interview: “Putinismus? Das Ist Völkische, Antiwestliche Rhetorik, Stalinkult Und Nackter Oberkörper“ | Kleine Zeitung,” Www.kleinezeitung.at, December 18, 2022.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

With over two decades of professional experience and academic background in security and defense Velina Tchakarova is an expert in the field of geopolitics. Velina ...

Read More +