-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

NGO-led one-stop centres in Mumbai provide critical services to GBV survivors, offering support, but face challenges in scaling up and ensuring consistent funding

Image Source: Getty

Globally, women face discrimination and inequality due to prevailing socio-cultural systems. These gender-based inequalities have long-term adverse effects on individuals and societies. Violence against women and girls also continues to be pervasive, with the determinants being multilevel and intersectional.

In India, different forms of daily aggression against women and girls are overlooked, and typically accepted as norms. According to the National Family Health Survey 2019-21 (NFHS- 5), 29.3 percent of married Indian women aged 18-49 years have ever experienced domestic violence. The actual incidence is likely to be much higher, as many of these crimes are left unreported. The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) has recorded an increase in the incidence of crimes against women, with 445,256 cases reported in 2022 against 428,278 in 2021. According to the same data set, Maharashtra is the state with the highest observed rise in crimes against women, increasing by 10-15 percent since 2021; Mumbai has one of the highest numbers of reported cases of sexual harassment and human trafficking of women across cities.

The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) has recorded an increase in the incidence of crimes against women, with 445,256 cases reported in 2022 against 428,278 in 2021.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has long recognised violence against women and girls as a global public health issue. Gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls is also a global action agenda item under the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goal 5 (SDG 5).

In 2015, the Ministry of Women and Child Development, Government of India, established One-Stop Centres (OSC), through the Nirbhaya Fund, to address the interrelated issues of violence against women. The centres are designed to provide survivors, in one setting, with different medical, psychosocial, and legal services. OSCs also facilitate temporary shelters for survivors, preferably in or near a hospital facility. At the district level, OSCs coordinate and converge with other initiatives, such as Anti-Human Trafficking Units (AHTUs), Women Helpline (WHL), Special Fast Track Courts (SFTCs), and District Legal Service Authorities (DLSAs). According to the Ministry of Women and Child Development, there are 752 currently operational OSCs in India, which have assisted 801,062 women between 2015 and 2023. However, these OSCs face challenges in ensuring the provision of critical assistance and support to women survivors of violence.

Mumbai and its suburban districts have an estimated population of 13.1 million. The city has a high incidence of crime, alcoholism, gender-based violence, and structural inequality, as well as a large migrant population who live in conditions of poverty.

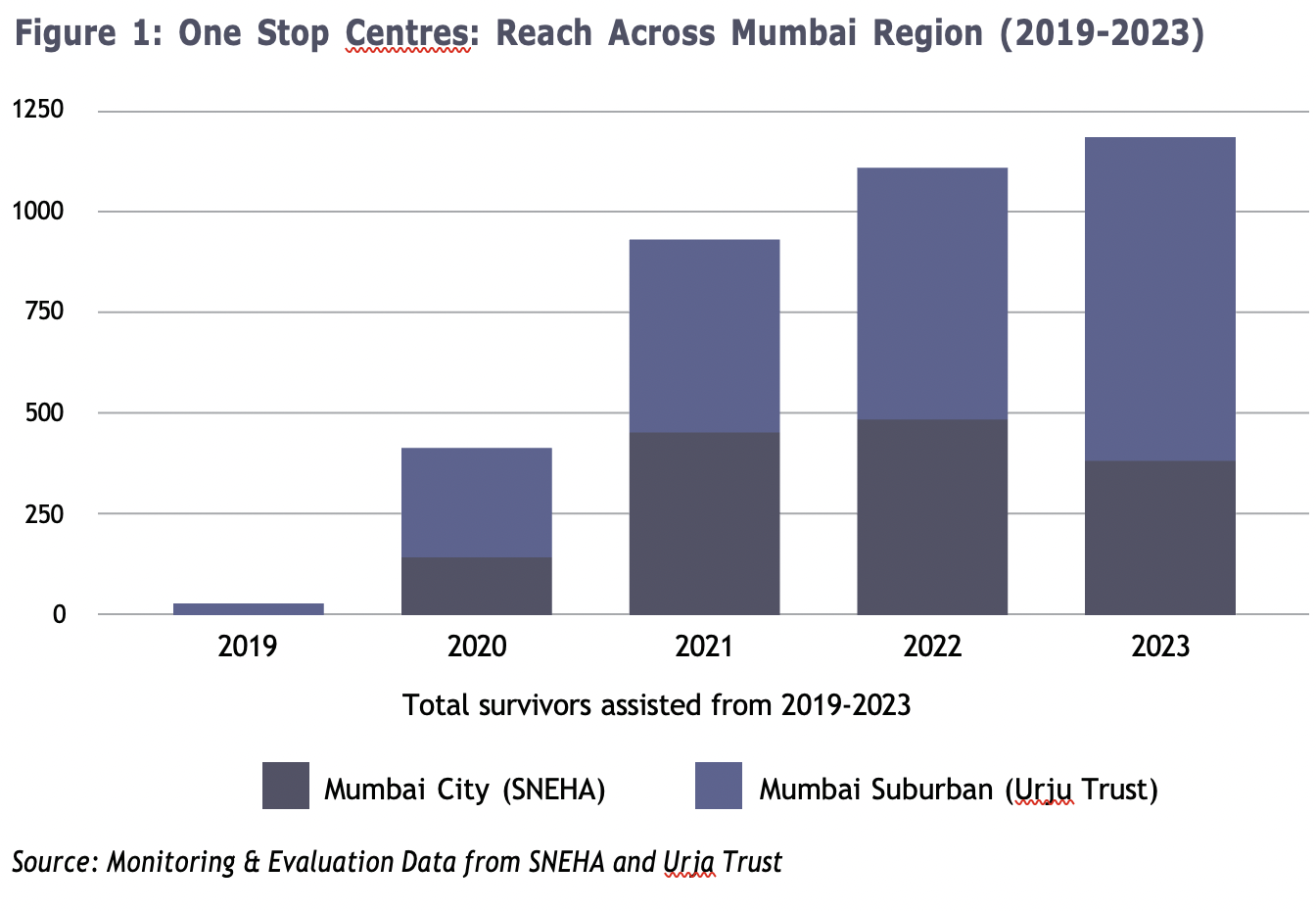

The Department of Women and Child Development (DWCD) launched the OSC scheme in the city with two NGOs that work across Mumbai and its suburban districts—the Society for Nutrition,Education and Health Action (SNEHA) and Urja Trust.

The Department of Women and Child Development (DWCD) launched the OSC scheme in the city with two NGOs that work across Mumbai and its suburban districts—the Society for Nutrition,Education and Health Action (SNEHA) and Urja Trust. Two OSCs were established—one at the King Edward Memorial Hospital (Parel) and the other at the Balasaheb Thackeray Trauma Centre (Jogeshwari)—which provide quality care and support to women and girls who are survivors of gender-based violence. Medical experts and OSC staff attend to survivors who visit the OSCs and facilitate the timely collection of samples for forensic testing. Survivors are not required to visit the police station to record their statements or file complaints. Despite limited resources and the rising incidence of violence, the OSCs have steadily expanded their reach.

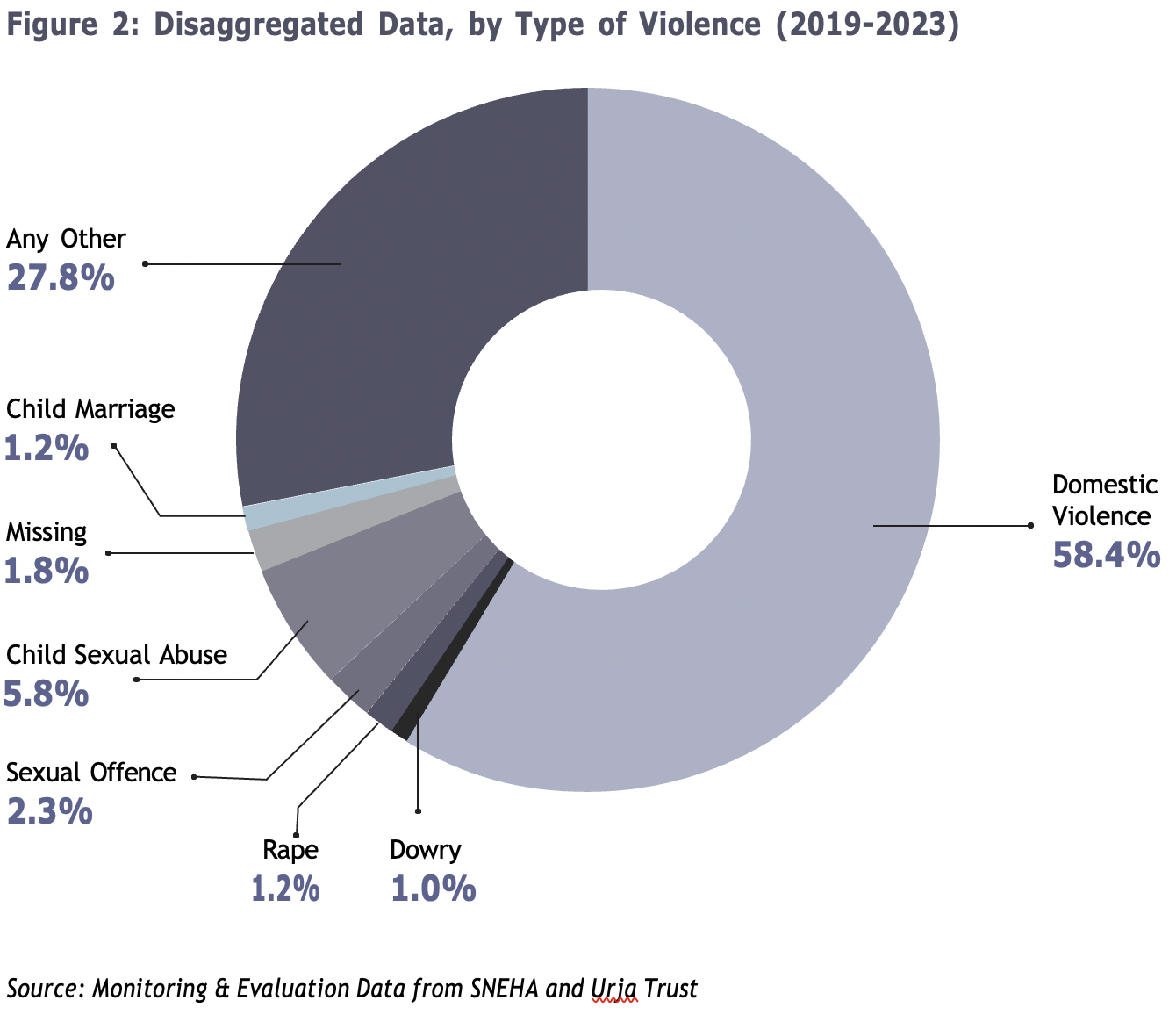

Given the relationship between trauma and violence, the OSCs also facilitate psychological aid through crisis counselling and extended counselling to the survivors. The OSCs also coordinate with public health officials, District Legal Service Authorities (DLSAs), protection officers, and the police (for FIR registration), and provide legal support. For survivors under the age of 18, they establish coordination with authorities under the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act 2000 and the Protection of Children from Sexual Offence Act 2012. More than half (58.4 percent) of registered cases involve domestic violence (see Figure 2), which raises significant concerns and emphasises the need to bolster prevention and redressal mechanisms and recognise domestic violence at the systemic and societal levels. Additionally, the rising number of reported cases of sexual violence against women and children necessitates coordinated efforts with the police, judiciary, child welfare committees, and social services to ensure effective and streamlined interventions.

OSCs help institutionalise a systemic response to survivors of violence against women and children. The government must examine the system’s responsiveness along a continuum of ‘prevention and response’ interventions to address gender-based violence. While managing OSCs has always been difficult, the mandates and responsibilities introduced by recent policy amendments and the Mission Shakti guidelines have made the implementation of OSCs an even bigger challenge.

Along with Mission Shakti’s sub-schemes, OSCs are central to promoting and facilitating alternative dispute resolution and holistic well-being as well as propagating gender justice in society and within families. They are also critical for the success of integrated efforts to ensure women’s safety, security, and empowerment. Therefore, in India’s rapidly expanding urban landscape, upscaling OSCs to widen their reach and improve effectiveness is paramount to the success of Mission Shakti.

Nikhat Shaikh is the Director of the Prevention of Violence Against Women and Children Programme at the Society for Nutrition, Education, and Health Action

Ankita K is the Head of Programmes at Urja Trust

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Nikhat Shaikh is the Director of the Prevention of Violence Against Women and Children Programme at the Society for Nutrition, Education, and Health Action ...

Read More +