India’s population and geography makes the process of public elections a rather arduous task. With major attention being paid by the

NITI Aayog in working with the Indian States to implement the

UN Sustainable Development Goals 2015 (SDGs), it is important to note that this would imply more accuracy in the federal Governance mechanisms both at the State and Union levels. Amidst the recent political battle for the 17

th Lok Sabha in India, we must pay attention to some of the major flaws in the electoral procedure for the largest democracy in the world, making SDGs implementation all the more difficult.

We must pay attention to some of the major flaws in the electoral procedure for the largest democracy in the world, making SDGs implementation all the more difficult.

The Delimitation Commission is endowed with the task of demarcating constituencies for the lower houses in the State and Union Parliament under the Delimitation Commission Acts that has been executed four times post independence in 1952, 1962, 1972 and 2002.

Article 81 of the Constitution postulates that: (a) the total number of existing seats in the Lok Sabha and the State Legislative Assemblies are “on the basis of 1971 census” that “shall remain unaltered till the first census to be taken after the year 2026,” which is in 2031 and (b) the State assembly constituencies are to be demarcated in a way such that each represents an equal population in the State assembly and for the identification of the number of parliamentary constituencies in each State, the ratio between that number and the State population should be approximately same for all States.

According to 1971

Census , the population of India was 548 million with a registered electorate of 274 million approximately. The last Census in 2011 shows that these figures have more than doubled to 1.2 billion and 834 million respectively, which have again grown exponentially until now in 2019.

The 42nd and 84th Amendment Acts facilitated the freeze on delimitation until 2026, based on controversies that the States which have been prompt in controlling population will be under represented in the Lok Sabha. Hence, considering population as a benchmark in the electoral process is grossly erroneous since the rationale of representation is highly biased, uses archaic and underestimated data and is ineffective. While

estimates suggest that a member of Parliament in UK represents 0.1 million people in contrast to an Indian one who represents 2.2 million people, the Indian democracy is failing to effectively represent its large pool of human capital which is crucially interdependent with all the SDGs.

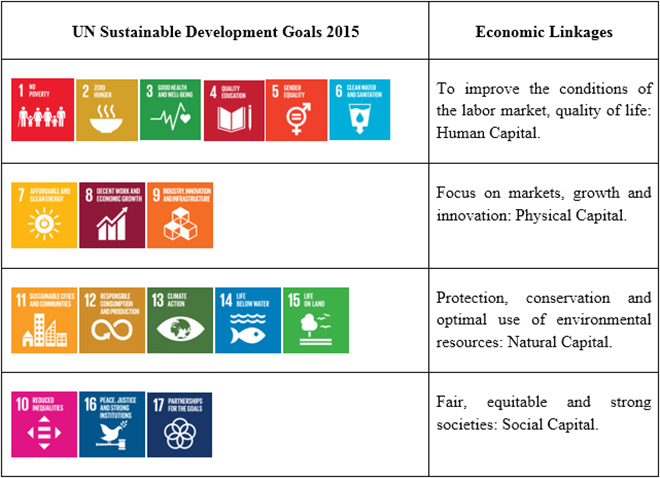

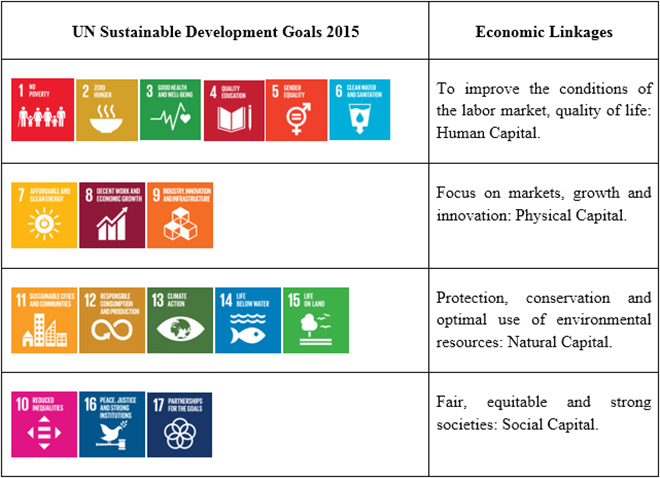

The following table shows that a closer look at the SDGs and their sub-goals would hint at bolstering the potentially available

physical, social, natural and human capitals for better input and output market conditions. It has to be understood that this a necessary prerequisite to boost, and more importantly sustain, the economic growth of the country.

It is evident that if we want our federal governance structure to promote the SDGs, we must also focus on the scale of geographical area of constituencies rather than only the population it holds. This could mean governance methods that would endorse adequate legislative representation, in terms of, protection and valuation of forests and wildlife, adequate use of land for infrastructure development, prevention of detrimental usage of land, deterring criminal activities in abandoned areas, etc. even if the particular geography is not inhabitated by a very large population.

If we want our federal governance structure to promote the SDGs, we must also focus on the scale of geographical area of constituencies rather than only the population it holds.

33% of the Lok Sabha will be captured by Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and West Bengal by 2026 in comparison to the scanty representation of the North Eastern States in the Parliament, where the latter have humungous amounts of natural capital, scope for physical infrastructure and excellent societal diversity. It is indisputable that population itself cannot be the sole basis which can depict all aspects of physical, natural and social capitals. We need a paradigm shift from just direct human welfare to other capital linkages over space that enhances the regional business climate, economic development and hence indirectly contributes to better quality of life.

The inter-linkage between the population factor and geographic space forms the basis of human capital. It is of paramount importance that, optimal availability and functioning of social, physical and natural assets is indispensable for human livelihood and well being. There should be more scope to focus on the electoral geography while delimiting constituencies, in the context of spatial election designs, updated statistics and long term outcomes.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

India’s population and geography makes the process of public elections a rather arduous task. With major attention being paid by the NITI Aayog in working with the Indian States to implement the UN Sustainable Development Goals 2015 (SDGs), it is important to note that this would imply more accuracy in the federal Governance mechanisms both at the State and Union levels. Amidst the recent political battle for the 17th Lok Sabha in India, we must pay attention to some of the major flaws in the electoral procedure for the largest democracy in the world, making SDGs implementation all the more difficult.

India’s population and geography makes the process of public elections a rather arduous task. With major attention being paid by the NITI Aayog in working with the Indian States to implement the UN Sustainable Development Goals 2015 (SDGs), it is important to note that this would imply more accuracy in the federal Governance mechanisms both at the State and Union levels. Amidst the recent political battle for the 17th Lok Sabha in India, we must pay attention to some of the major flaws in the electoral procedure for the largest democracy in the world, making SDGs implementation all the more difficult.

It is evident that if we want our federal governance structure to promote the SDGs, we must also focus on the scale of geographical area of constituencies rather than only the population it holds. This could mean governance methods that would endorse adequate legislative representation, in terms of, protection and valuation of forests and wildlife, adequate use of land for infrastructure development, prevention of detrimental usage of land, deterring criminal activities in abandoned areas, etc. even if the particular geography is not inhabitated by a very large population.

It is evident that if we want our federal governance structure to promote the SDGs, we must also focus on the scale of geographical area of constituencies rather than only the population it holds. This could mean governance methods that would endorse adequate legislative representation, in terms of, protection and valuation of forests and wildlife, adequate use of land for infrastructure development, prevention of detrimental usage of land, deterring criminal activities in abandoned areas, etc. even if the particular geography is not inhabitated by a very large population.