From March 15 to 17, Russia held presidential elections. About 112 million people were eligible to vote inside the country and 1.9 million eligible voters were able to cast their ballots abroad.

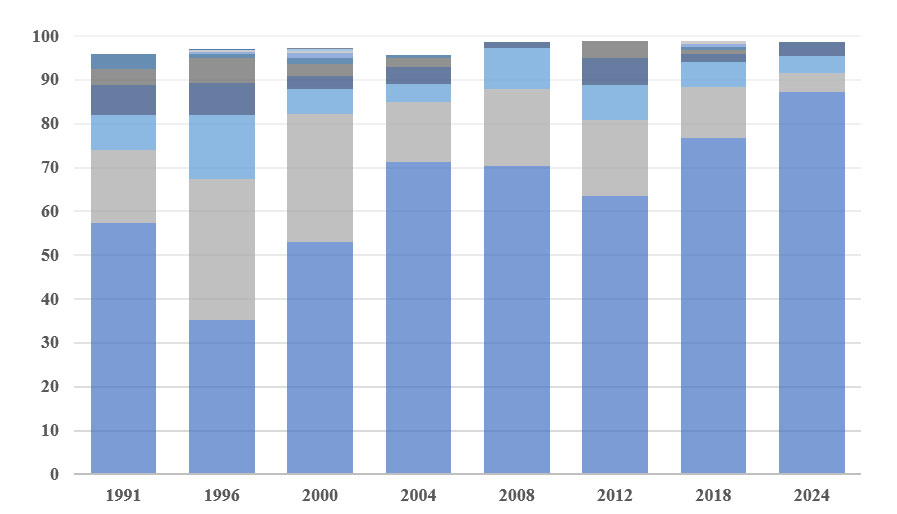

The incumbent president Vladimir Putin gains 87.32 percent, according to the data from the Russian Center Election Commission. The opposition candidates combined received less then 12% of votes. The outcome of the elections may appear predictable. All the same, these estimations hardly encapsulated the nuanced complexities of the electoral landscape due to some distinctive features which underlie the current political process. Notably, 33 nominations were filed, representing a very diverse political spectrum. Among these candidates, there were some representing an anti-military stance, coupled with certain liberal agenda platforms. Second, the system opposition parties are facing difficulties related to “generational change”, which manifested itself in gradual displacement of ‘political dinosaurs’ from amongst leaders of the LDPR (Liberal Democratic Party of Russia) and CPRF (Communist Party). In their stead, new figures emerged. Third, the current elections are happening against the backdrop of the Ukrainian conflict. The electorate comprises not only residents of the new regions but also those who have fled Russia. Fourth, it is the first time when electronic voting is being used during the presidential elections.

Candidates

The final ballot includes only four candidates. The number is a historical low in modern Russian history, mirroring the count of contenders during the 2008 elections, which saw the victory of Dmitry Medvedev.

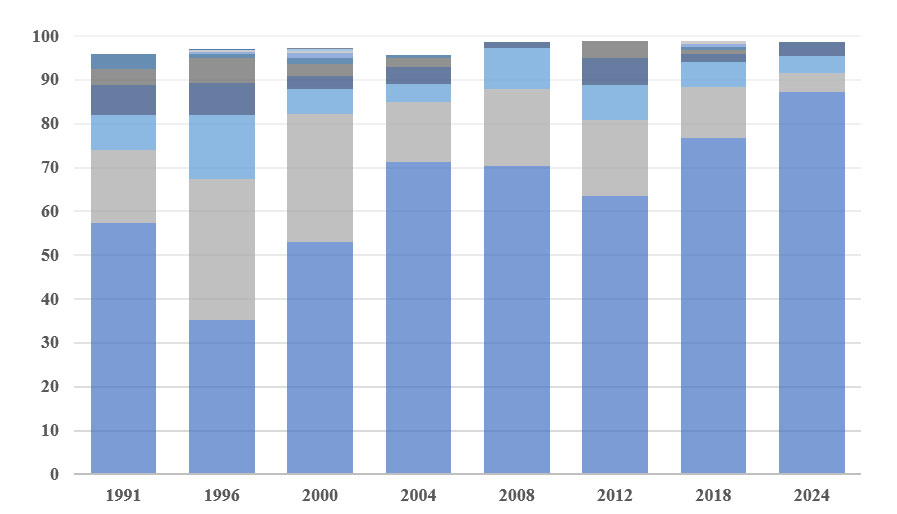

The «palette» of Russian elections – distribution of votes among candidates

Source: Central Election Commission of Russia

The “generational shift” within LDPR and CPRF is occurring with huge reservations. On the one hand, we saw some efforts to refresh the apparatus with new leaders. Gennady Zyuganov (CPRF), a politician of the 1990s-era, was replaced by businessmen Pavel Grudinin as a candidate in 2018; and after the death of Vladimir Zhirinovsky in 2022, now 56-year-old Leonid Slutsky has become the leader of LDPR. However, today, the communists are represented by 75-year-old Nikolai Kharitonov. Both of them were candidates for the presidency, but suffer from being in the shadow of media recognition of their predecessors. This is one of the reasons why they have not yet been able to clearly enunciate a new political narrative and agenda of their parties. Another fresh face is 40-year-old Vladislav Davankov, representing the “New People” party formed in 2020. Many hoped he would revitalise the political sphere.

Despite the limited pool of final candidates, the registration process was marked by some unpredictable features. The candidates can participate in elections as self-nominated independent candidates or from one of the political parties. According to Center Election Commission (CEC) requirements, after the registration, they are allowed to start political campaigning. As a part of electoral process, the candidates are to collect signatures from the supporters. The minimum number of signatures from the parties not represented in the parliament is 100 thousand, and for self-nominees is 300 thousand.

The candidates can participate in elections as self-nominated independent candidates or from one of the political parties.

Out of 33 initial applications, only 15 were accepted due to compliance with formal requirements. Of them, seven were eliminated because they urged voting for other candidates. Another four were rejected because of the final nomination conditionality—collecting a required number of signatures in support of the candidate. The excess of invalid signatures for a candidacy, notably resulted in the exclusion of Boris Nadezhdin, a popular candidate and key representative of the non-systemic opposition. The CEC claimed that more than 15 percent of the collected signatures were defective, above the prescribed limit of 5 percent.

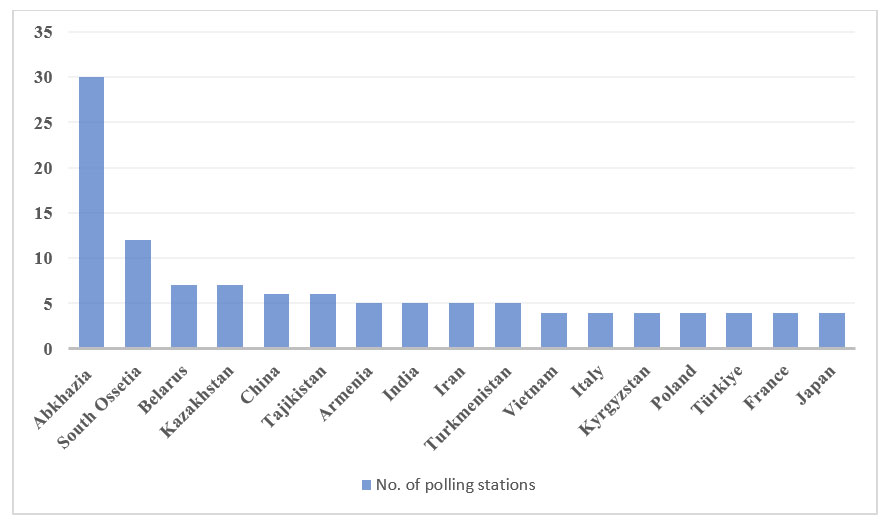

Voting abroad

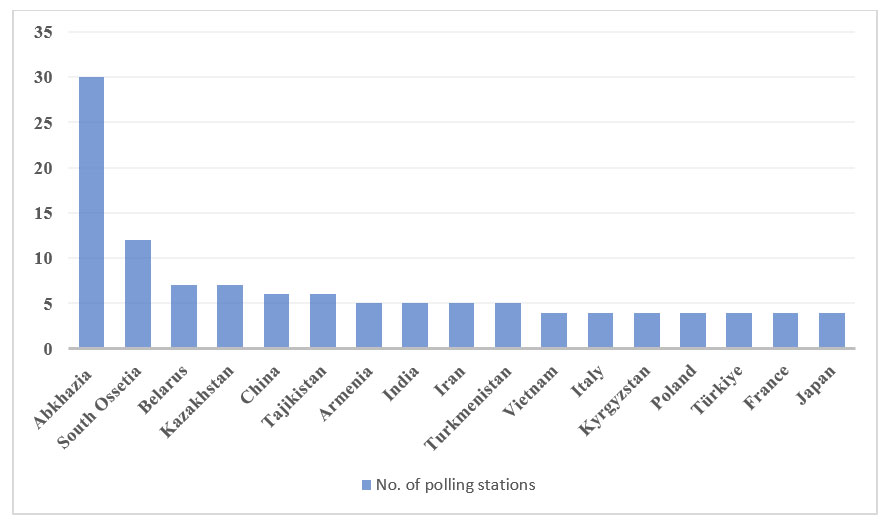

Another pressing issue was the process of voting abroad, which took place against the backdrop of geopolitical tensions and was further fuelled by an increase in migration flows. The largest number of polling stations were located in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, numbering 30 and 12 respectively. Although these regions harbour a relatively small population, a significant number of people there hold Russian citizenship, mainly due to streamlined procedures of acquisition – 50 percent of Abkhazia and 95 percent of South Ossetia.

No. of polling stations abroad

Source: https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/6524296

A total of 295 polling stations opened abroad marks a decrease from the preceding election cycle’s count of 394, a trend officially attributed to constraints stemming from shortages in consular personnel and heightened security considerations.

In some countries, the problem of access to voting systems manifests itself more seriously. In Georgia, voting arrangements are unfeasible due to the absence of diplomatic relations. In Estonia, objections were raised against the holding of Russian elections outside embassy premises, resulting in a significant reduction from nine to one polling station compared to 2018. A similar situation unfolded in Lithuania, where number of polling stations has dwindled from five cities to solely one within the embassy confines in Vilnius. In Latvia, only two polling stations operated within the embassy in Riga.

New territories

The number of new electorate in the Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR), the Luhansk People’s Republic (LPR), as well as in the Zaporizhzhia and Kherson Oblast is approximately 4.56 million people. The voting there commenced towards the end of February, particularly in the areas proximate to the front lines. The areas were formally designated as “hard to reach”, necessitating early voting for citizens and participants in military operations. Stationary polling stations were opened near the contact line, and many of the military personnel voted at permanent polling stations rather than temporary ones. As a precautionary measure, the locations of precinct commissions were not publicly disclosed. It is anticipated that early voting turnout will exceed the previous election cycle's participation rate of 220 thousand voters. The turnout ranged from 36 percent in the DPR to 58 percent in the Kherson region, underscoring the heightened engagement in these territories.

The areas were formally designated as “hard to reach”, necessitating early voting for citizens and participants in military operations.

Digital voting

The utilisation of electronic voting systems marks a pioneering inclusion in the presidential elections, albeit having been partially employed in local elections previously. Notably, the Central Election Commission projected a potential participation of 38 million voters, yet the actual number of individuals expressing a desire to utilise this new tool stands at 4.9 million. The advent of electronic voting has elicited both advocacy and critique. The Government touts its efficacy in streamlining bureaucratic processes and curtailing financial expenditures. However, public scepticism regarding transparency persists, with potential cyber threats further amplifying apprehensions among authorities.

While these developments did not sway the final voting outcome, they hold significance in understanding the dynamics of people’s behaviour, social demographics, and the proportion of votes garnered. Although electoral outcomes ostensibly shouldn't significantly change foreign policy, they may serve as a yardstick for assessing the efficacy of political and economic decisions. As such, the forthcoming weeks promise insights into potential ramifications on broader policy narratives.

Ivan Shchedrov is a Visiting Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV