-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

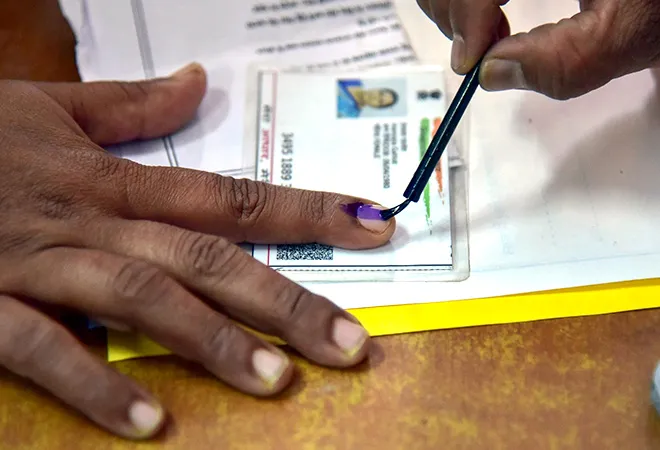

The Election Commission of India (ECI) mocked by the Supreme Court for being lethargic and pleading helplessness, has decided to flex its muscles and demonstrate its clout. To prove that it is not quite the ineffectual defanged authority that the judiciary has made it out to be, the ECI has sought to tame violators of the Model Code of Conduct which politicians are expected to comply with during elections. Four politicians have been barred from campaigning for a period ranging between two and three days. Among them are Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath, BSP’s supreme leader Mayawati, senior SP politician Azam Khan and BJP candidate Maneka Gandhi. They have been found in violation of Section 123 (3) of the Representation of the People Act, the law under which elections are held in India and prohibits the “appeal by a candidate or any other person with the consent of the candidate or his election agent to vote or refrain from voting for any person on the ground of his religion, race, caste, community or language”.

In itself, the penalty imposed by the ECI is laudatory to the limited extent that it upholds the law. But viewed against the backdrop of numerous violations that have escaped scrutiny and punishment during the ongoing election campaign and the impunity with which some politicians continue to transgress restrictions on what can and cannot be said while soliciting votes, there is very little to write home about the forced benching. The day after the ECI cracked the proverbial whip, a popular Congress lawmaker, Navjot Singh Sidhu, brazenly appealed to Muslims to vote for his party and block Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s return to power. This was expectedly amplified by Pakistan Radio. Azam Khan’s son has accused the ECI of targeting his father because he is a Muslim. The discourse will get coarser as this summer’s election winds its way through an increasingly bitter and incredibly long campaign.

The ECI has begun to resemble, and alarmingly so, a censor board with sweeping arbitrary powers to control both campaign and non-campaign media content

Meanwhile, the ECI has begun to resemble, and alarmingly so, a censor board with sweeping arbitrary powers to control both campaign and non-campaign media content. The commercial release of a biopic on Modi cleared by the Central Board of Film Certification, along with other biopics, has been put on hold. It’s a first of its kind imposition of censorship during elections. As an institution the ECI never reacted to protests against an openly partisan film, ‘Udta Punjab’, whose commercial release was planned to coincide with the Punjab Assembly elections. Neither the film nor the issue of rampant drug abuse it claimed to flag has been heard of after the election. The Akali Dal, however, remains tainted with the allegation that its leaders were involved in promoting the alleged mass drug addiction among young Punjabis. The story does not end with blocked biopics, good or bad. We are now told producers of television serials will have to seek clearance from the ECI if they have any political content. People are receiving ECI notices for what they print on wedding invitation cards. Social media platforms are being asked to suspend Twitter handles and take down pages. Publishers of books could find themselves being subjected to similar scrutiny. Newspapers and journals could follow. As was said of Soviet-style censorship and thought control, from absurdity we are fast moving towards greater absurdity.

Lost in all of this is the abysmal state of affairs in West Bengal where free and fair elections are proving to be a farce. Enough evidence exists, and has been submitted to election authorities, to merit intervention by the ECI. Barring cosmetic transfers of a few police officers, there has been no response so far, not even a mild reprimand, for the glaring transgressions. In Tamil Nadu, vitriolic communal abuse in the guise of ideology has become the staple of certain politicians. We also have glaring examples of how the relentless repetition of lies meant to sway and mislead voters has become the daily campaign routine of a prime ministerial aspirant – even the Supreme Court has been wantonly misquoted as having said something that, in reality, it never said.

If inducing voters with offers of money is a punishable offence under the Representation of the People Act, then that offence is being committed without either the scantest regard for the law or fear of the consequences of its violation

If inducing voters with offers of money is a punishable offence under the Representation of the People Act, then that offence is being committed without either the scantest regard for the law or fear of the consequences of its violation. All it requires is a mention in the Manifesto that if voted to power, so much money will be handed out to voters in the guise of some welfare scheme or the other. That trick enables politicians to lure voters with promises of money and prevents the Election Commission from applying the law against monetary inducement. Sometimes even that fig leaf is not required: In Andhra Pradesh, money was promised for building churches and homes for pastors. Pandering to minorities can come in many forms, as can influencing the way they vote. Two popular Bangladeshi actors have been campaigning against the BJP in West Bengal, one of them in Muslim-dominated areas which also happen to be populated with illegal Bangladeshi immigrants whose names now magically feature on voters lists prepared by the ECI, either directly or under its supervision. The church in India is no stranger to issuing partisan ‘appeals’ to the laity or using Sunday sermons to propagate political views. The video of a Goa priest telling his congregation that Manohar Parrikar’s cancer was the ‘wrath of god’ and other such spiteful things while instructing the faithful which way to vote has gone viral. Yet the church claims it is neutral and hence above opprobrium. The Jamaat-e-Islami Hind has issued a pamphlet in support of ‘secular’ parties and against 'fascist' forces; elections in India are not without understated irony.

There’s a lot more that militates against what is called ‘free and fair elections’. A parallel campaign is being run on social media, including WhatsApp groups, where virulent and vile messaging more often than not goes unnoticed or remains encrypted, away from the ECI's eyes gifted with selective sight. Journalists who raucously proclaim they are free of bias wear their political preferences on their sleeves and disingenuously mainstream everything that is antithetical to the spirit behind the law that has been invoked to punish four politicians. Primetime television can loudly debate caste coalitions and minority votes, op-eds can forecast and analyse voting patterns on the basis of community identities, academics can hold forth on identity politics, but all this and more cannot be mentioned from a campaign platform. The Model Code of Conduct kicks in after parties on the basis of their caste and community select candidates. 'Winnability' is all about getting the complex sum of demographics right. Such are the realities that are glossed over while all eyes are riveted on the Great Indian Rope Trick called 'Model Code of Conduct'.

If elections are indeed a celebration of democracy, then we should ask whether curbs on free speech, the essence of any democracy, should exist on the campaign trail

Lastly, if elections are indeed a celebration of democracy, then we should ask whether curbs on free speech, the essence of any democracy, should exist on the campaign trail. It could also be argued that if caste, community and religion play a decisive role in the selection of candidates, should the mention of caste, community and religion in campaign speeches be prohibited? How deeply flawed is a law which permits political parties with communal names and casteist agendas but disallows communal and caste-based mobilisation? Why is it that what can be openly discussed and deliberated in television studios and ponderous commentaries must remain hidden behind the veil of duplicity at election rallies? Should the law enforce a distance between the spoken word and the actual deed on voting day?

These and other questions must be raised, if only to test how valid are restrictions that were designed for an era that has long ceased to exist – some would say that era never existed. This is all the more so with the advent and rise of technology that, in coming years, will begin to give, if not replace, physical election rallies a run for their money. Any politician who is a serious contender for power will tell you that the biggest influencers in this year’s election are not ‘star campaigners’ but faceless backroom content strategists who are crafting targeted digital messages for voters across the country. This is India’s first big data election – data is being finely parsed to drive the other campaign on WhatsApp, of which there is little known and even lesser understood by those cheering or jeering the Election Commission of India.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Kanchan Gupta was a Distinguished Fellow at ORF. His work focuses on Indias political economy. His areas of interest are domestic politics and the Middle ...

Read More +