-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

An analysis of how the DHIS2 open-source platform was used in Sri Lanka, Norway, and Uganda during the COVID-19 pandemic

The DHIS2 is a web-based open-source platform that is most used as a health management information system (HMIS). DHIS2 is currently the world's largest HMIS platform, in use in 73 low- and middle-income countries and covering approximately 2.4 billion people. The core development of the platform is coordinated by the University of Oslo (UiO), Norway, and is globally implemented by numerous partners and the HISP network. HISP is a global movement that promotes DHIS2 as a global public good by assisting with implementation, local customisation and configuration, and providing in-country and regional training. The platform has been widely used in the health domain over the last three decades, and is increasingly used in supporting information management in non-health sectors such as education.

The DHIS2 platform has been used as a means of managing communicable disease outbreaks for several years, as notably highlighted during the 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. In the aftermath of the Ebola epidemic in 2015, Guinea's Ministry of Health established a strategic plan to strengthen its surveillance system, which included the adoption of DHIS2 as a health information system capable of capturing surveillance data. Guinea, a resource-limited country, implemented aggregated disease surveillance in a well-structured manner, starting with pilot project in two regions, before it was scaled up to a national level programme, and finally expanded to a case-based digital surveillance system over four years. Therefore, the use of DHIS2 during the Ebola epidemic nourished the platform with features and functionalities for outbreak management and provided valuable experience to the implementation community.

HISP is a global movement that promotes DHIS2 as a global public good by assisting with implementation, local customisation and configuration, and providing in-country and regional training.

This essay highlights the use of DHIS2 during the COVID-19 pandemic in three countries: Sri Lanka, Uganda, and Norway. It presents the drivers needed for effective and trusted adoption and use of digital public goods (DPGs) in these different contexts, along with a discussion on how DPGs can be leveraged for digital sovereignty. Our study finds that, for a country to fully claim ownership of and sustain digital public infrastructure (DPI), without relying on an external entity, requires extensive capacity building, including skilled technology talent, a participatory design process, sustained engagement by relevant government agencies, and multisector engagement.

As a global DPG, DHIS2 contributed to COVID-19-related information management in more than 50 countries during the pandemic. More importantly, the implementations were conducted in an agile manner with minimal intervention from global consultants supporting those countries.

COVID-19 emerged in December 2019 in China and rapidly spread to several countries in the Asian region. Sri Lanka, which records the second highest numbers of annual tourist entry by country from China, had concerns about preventing the entry and spread of the coronavirus in January 2020. The Sri Lankan health ministry established a digital information system to conduct surveillance and coordination between stakeholders involved with decision-making related to COVID-19. However, they had several major concerns regarding the development and implementation of this solution, including building a system that could accommodate changing requirements based on disease epidemiology; training staff from multiple sectors on a new digital solution in a short of time; creating collaboration between stakeholders in traditionally less-flexible government set-up; and acquiring a digital system as per rigid government procurement criteria.

The Sri Lankan health ministry established a digital information system to conduct surveillance and coordination between stakeholders involved with decision-making related to COVID-19.

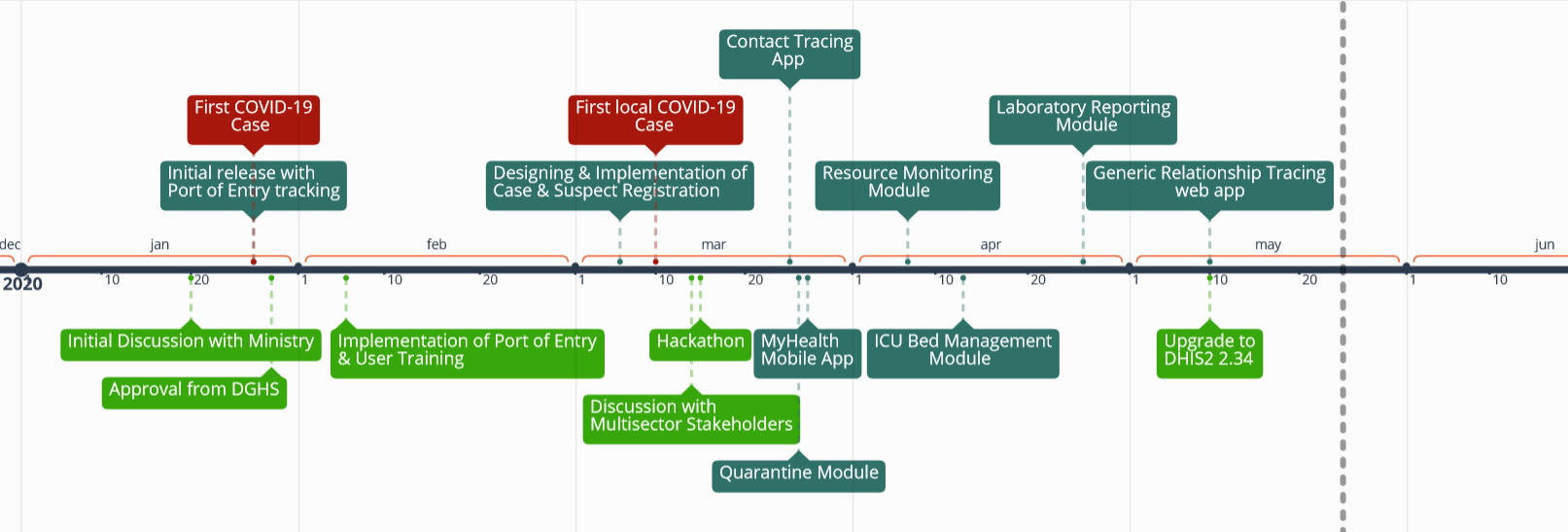

Specialists trained in medical and health informatics were instrumental in leading the discussions around such concerns with health sector administrators. Following these discussions, the ministry decided to develop a digital information system based on the DHIS2 platform, which was already widely used in the local health sector and had significant capacity at all levels in the health hierarchy. The design and implementation of this platform was led by HISP Sri Lanka, alongside the health ministry and the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Agency of Sri Lanka. The country was able to design the prototype of the port of entry monitoring module on the DHIS2 platform, which was ready for implementation by the time Sri Lanka reported the first case of COVID-19. Sri Lanka was able to design more than eight modules in the system within four months, including customising the generic platform (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Development of Digital Information System Modules (January-June 2020)

Source: Designed by the author

Source: Designed by the author

The production of these innovations was catalysed by the local HISP group in collaboration with UiO, the global HISP community, and the government ICT agency, which coordinated the involvement of volunteer developers by organising a hackathon. Multisector stakeholders, headed by COVID- 19 steering committee, supported the implementation of the system.

The experiences and the metadata from Sri Lanka was shared with the UiO DHIS2 core team and the global HISP community, which led to the production of the DHIS2 metadata package for COVID-19 that was adopted by more than 40 countries.

In the latter half of 2020, HISP Sri Lanka and the health ministry customised DHIS2 to capture COVID-19 vaccination data by pre-registering the country’s entire adult population. The immunisation module was ready by the time the country received its first stock of vaccines in January 2021. This metadata was also shared with the global DHIS2 community, which contributed to the development of the immunisation metadata package. To produce a digital vaccination certificate, the HISP Sri Lanka team and the government ICT agency collaborated to integrate DIVOC (a DPG) on the DHIS2 platform.

Uganda, a landlocked country in East Africa, is heavily dependent on supplies from Kenya and Tanzania across its borders. From the start of the pandemic, Uganda encountered the challenge of tracking and allowing truck drivers transporting goods to enter the country. To ease this process, Uganda utilised the port of entry component of the DHIS2 metadata package and enhanced it further to local requirements by producing a mobile application to track truck drivers at different points along their journey. Innovations by the Uganda team, such as the inclusion of features to support QR codes in the DHIS2 android capture app, also contributed to the expansion of the DHIS2 core platform.

Uganda capitalised on the existing electronic integrated disease surveillance and response that was implemented in 2012 to build-in the COVID-19 reporting module at school level using the DHIS2 for education (DEMIS) system.

Furthermore, Uganda also implemented DHIS2 in the education sector to report on the COVID-19 infection status of schoolchildren. Uganda capitalised on the existing electronic integrated disease surveillance and response that was implemented in 2012 to build-in the COVID-19 reporting module at school level using the DHIS2 for education (DEMIS) system. This facilitated bringing students back to schools following extended periods of school closure due to the pandemic.

Norway, a highly digitalised country, also had the challenge of using efficient digital tools in contact tracing in the early phase of the pandemic in 2020. Tromsø municipality in northern Norway sought UiO’s assistance in producing a scalable digital solution for this purpose in March 2020. Given the successful deployment of DHIS2 in several countries for coronavirus surveillance, the DHIS2 core team designed a digital solution for Tromsø, and that was eventually used by over 130 municipalities in the country. This was the first major DHIS2 implementation in a European country.

However, the Norwegian implementation encountered several challenges due to existent complex digital solutions and integrations. The system had to be integrated with the existing identity platforms, and testing and vaccination databases to minimise the workload of the health staff and to properly align with the prevelant information architecture. The local innovations around integrations also contributed to the enhancement of the generic DHIS2 platform and its core capabilities of integrations.

In the discussion, we try to focus on identifying generic factors which enabled robust implementations in countries and how they addressed the concerns around sovereignty.

Analysis

Based on the three country scenarios discussed, the learnings from the HISP network across the implementations during the pandemic, and existing research on these implementations, we identify key factors that have contributed to implementing robust systems that also address the concerns around digital sovereignty.

The experiences of Sri Lanka, Uganda, and Norway suggest significant local capacity in customising and implementing the DHIS2. Sri Lanka, for instance, invested in a 10-year capacity-building graduate programme that produces individuals capable of building capacity at the national and district level across all categories of health staff. All three countries had local HISP groups connected with the global HISP network. These provide robust capacity to develop systems that are agile in nature, especially during health crises. The flexible, generic nature of the established DHIS2 platform also contributed to robustness.

Sri Lanka, for instance, invested in a 10-year capacity-building graduate programme that produces individuals capable of building capacity at the national and district level across all categories of health staff.

The local groups have worked closely with the health and other ministries in each country with a cross-sector collaboration, and built trust in delivering high-quality products and providing long-term support. Such long-term relationships supporting the local requirements are crucial in times of crises like the pandemic where existing procurement procedures had to be fast-tracked and agile methods adopted. The countries also built local innovations to address the dynamic requirements during the pandemic, thereby making the generic platform more relevant to the local context. The sharing of local innovations across a global network accelerated the dissemination and adoption of proven technology across the implementing countries.

The production of metadata packages ensured that the standards and best practices in information management were observed during the implementation, which also contributed to the security perspective of the data collected since adopting an open-source platform ensures some credibility and security. In the case of Sri Lanka, the government entity in charge of cybersecurity closely observed and provided recommendations for implementing the DHIS2 platform and the innovations around it throughout the implementation process.

Digital sovereignty can be understood as the control of data and what it represents during the use of technologies and computer networks.

The countries also built local innovations to address the dynamic requirements during the pandemic, thereby making the generic platform more relevant to the local context.

DPGs, by definition, render open-source solutions that produce a solid base for countries to adopt and localise. However, for a country to fully claim ownership of and sustain a system without relying on an external entity, extensive capacity building is needed. Both Sri Lanka and Uganda had long-standing capacity-building programmes within the government sector to produce skilled individuals capable of sustaining the DHIS2 platform. In addition, local experts built and implemented the technologies with assistance from the ministries and other stakeholders, enforcing a participatory approach in the development and implementation stages. This is required to make the software relevant and for countries to fully own the implementation. Activities such as the hackathon organised by Sri Lanka’s ICT agency provide a solid base for the country to have local infrastructure and architecture in place to establish and manage the data as per its jurisdiction. In all three countries, the local HISP groups played a supporting role while the ministries owned the information system and the data that creates the path to achieving digital sovereignty. The Sri Lankan example also showcases multisector engagement in implementation, which is crucial for the whole-of-government approach. For instance, the military took on the data entry burden, which can be seen as sharing ownership in the implementation process.

DHIS2 emerged as an extremely impactful DPG solution across many countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Being a flexible generic open-source solution that supports innovation enhanced the local adoption of the platform and helped maintain its relevance. In-country capacity building, participatory design, and engaging with open-source networks is crucial to ensure a robust implementation. Engaging with multisector stakeholders, capacity-building activities, supporting infrastructure, and digital architecture are crucial to ensure digital sovereignty when implementing DPGs in the times of a pandemic.

In the Sri Lanka, Uganda, and Norway experiences, sharing innovations and best practices with the global community was crucial. Indeed, having an active community behind a DPG is important for reliability, responsiveness, and sustainability.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.