This is the 107th article in the series

This is the 107th article in the series The China Chronicles.

Read the articles here.

COVID-19 related lockdowns have made a comeback in Western countries; the global economy continues to suffer from these disruptions. Most countries are among the losers in this scenario. China seems to be the biggest gainer till now. It has grown by 4.9 percent in the third quarter of 2020, and the combined growth rate of China in the first three quarters now stands at 0.7 percent. Retail sales have gone up by 3.3 percent in September. However, the first nine months of 2020 saw a combined 7.2 percent contraction in retail sales.

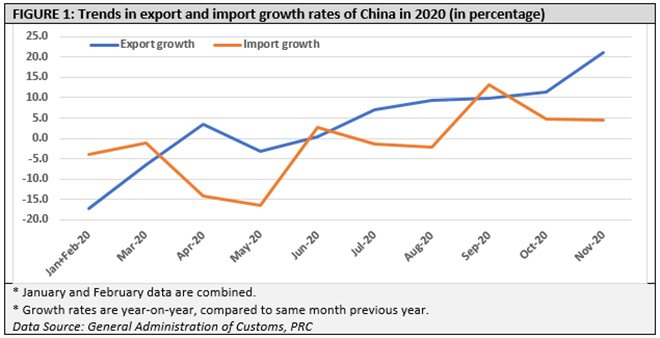

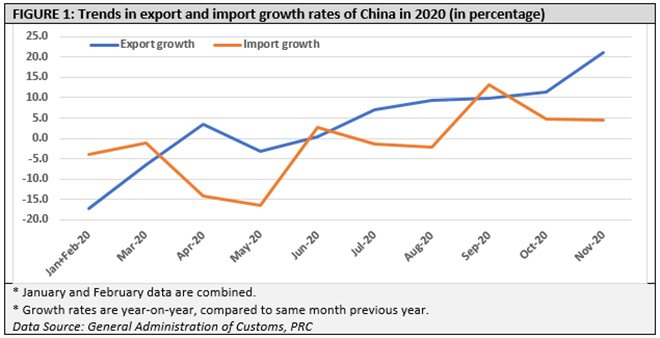

China’s exports have grown by 21.1% in November, after growing 11.4% in October (Figure 1). This is the highest growth rate in exports since February 2018. Exports have been growing steadily for six consecutive months now. It seems that Chinese factories are currently reaping the benefits accrued from imposition of new restrictions in Western countries.

Chinese imports have also recovered from the (-)16.6% growth in May 2020 to 4.5% in November. For three consecutive months, imports have been growing. There has always been a gap between industry supply and consumption demand in China. But exports and imports growing in tandem signifies a general revival of economic activity. This is an aspect missing in recent performances of almost all major economies. China is undoubtedly in an advantageous situation, at least for the time being.

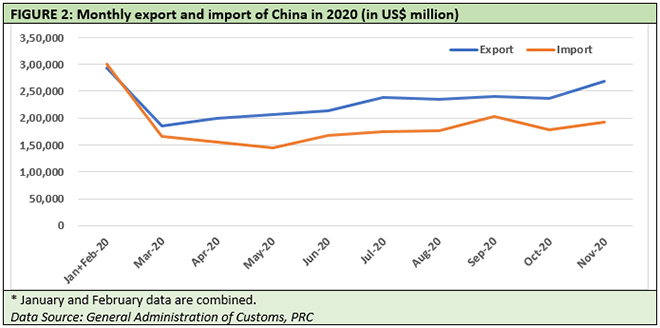

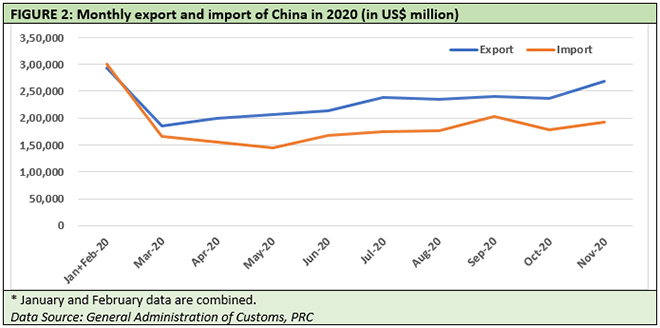

After August 2020, China’s trade surplus started shrinking for some time, before widening again after September. The trade balance almost disappeared at the beginning of this year when the pandemic struck. China managed the initial wave of infections reasonably well and was among the first few countries to ease restrictions in March, and the results are now showing (Figure 2).

As mentioned, retail sales recovery in domestic market is not exactly matching growth in other macroeconomic fundamentals. This could have resulted in increase in inventories and created problems for China, but a steady export performance is taking care of that right now.

However, China will have to grapple with rising unemployment, drop in household income and shifting consumer spending pattern (that may adversely affect consumer demand) in near future. Therefore, export remains a crucial engine of continuing economic ascendancy.

Outside China, this economic and trade performance in pandemic times is bound to escalate the decoupling discussion. Rising Chinese economic might in the last two decades and its recent geopolitical aggression ignited this debate.

With its induction into the WTO in 2001, China gained market access in advanced economies, which served its economic advancement well in the next two decades. However, those advanced countries also overlooked many Chinese transgressions that were against the norms of an international rules-based trading and economic order. In the process, China transformed into the global manufacturing hub, producing close to 30% of the world’s total manufacturing output.

Those transgressions continued when COVID-19 originated in Wuhan. Instead of sharing information to unitedly fight the pandemic, the country is still making attempts to divert attention by promoting counterfactual narratives.

Hence, it is no wonder that governments across the world are contemplating and rethinking strategic engagement and trade practices with China. The USA, under the Trump Presidency, was already at loggerheads with the country on the trade front. Serious discussion on limiting engagement with China was taking place at the European Union (EU) level also.

Hence, decoupling from China — as a discussion point — has taken centre stage in the last few months.

But, how feasible are the chances of such a decoupling right now?

If one looks at the region and country-wise composition of Chinese trade data in November 2020, then chances for implementation of decoupling appear very slim — at least for the time being. Around 32.6% of total cumulative Chinese exports till November 2020 have gone to the USA and EU countries. If Chinese exports to Japan, Canada, Australia, and the UK are added to that figure, then it would be close to 45% (Figure 3).

This demonstrates two facts. First, the advanced economies are still reeling under the severity of the pandemic and are not at all prepared for any kind of decoupling. Second, these economies may do more harm to themselves if they decide to decouple hastily without a cohesive plan.

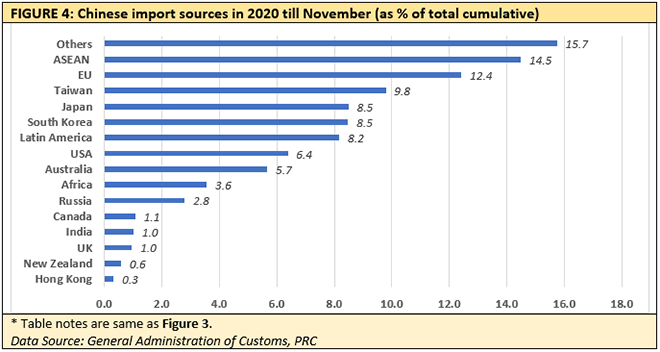

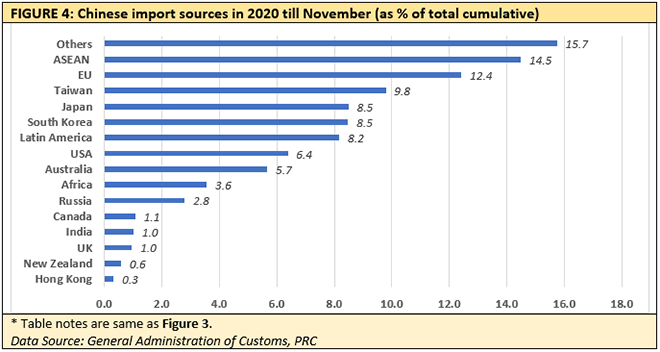

If import sources of China are examined, then it becomes clearer. China sourced close to 19% of its imports from the USA and the EU. Once again, if imports from Japan, Canada, Australia, and the UK are added to the tally, the figure is around 35%. Interestingly, close to 16% of Chinese imports in 2020 have been sourced from countries which are not major trade partners or major economies (Figure 4).

This signifies another important aspect of current international trade composition. While the countries seemingly interested in decoupling are import dependent on China, China itself is not import dependent on these countries. Though corresponding import and export baskets need to be analysed and checked in detail, the broader figures are not conducive for a decoupling from China.

China’s aggressive assertion and ambition to be a dominant world player and thus becoming “the new rule maker of a new rules-based system (which suits the country’s self-interest)” is bound to evoke apprehensive reactions from other countries. Decoupling trade is one of those. However, it is easier said than done when there is no concerted international plan to do so. Latest Chinese trade data succinctly demonstrates that.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This is the 107th article in the series The China Chronicles.

Read the articles

This is the 107th article in the series The China Chronicles.

Read the articles

PREV

PREV