Political funding is a murky business in all democracies, big or small, old or new. Illegal, under-the-table donations intending to buy influence or policy/regulatory favors have clouded all democracies and India is no exception to this trend. The recent addition of new political financing scheme named Electoral Bonds (EB) by the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government in 2017 has aroused huge public interest for its alleged role in furthering the murkier trends in political funding. A series of recent revelations by Right to Information (RTI) activist Lokesh Batra have brought to the public knowledge the manner and methods in which the government of the day ignored the warnings and reasoned voices of key independent institutions such as the Reserve Bank of India and Election Commission to push the law into effect. Not only has the business rules were bended at will to facilitate easy flow of donations, every effort has been made to keep this new scheme opaque and out of reach from the public.

Why Electoral Bonds?

While the controversies will continue hogging the EB, it would be useful to know about this novel scheme, key motivations behind its introduction and likely implications of such scheme for democracy and governance. EB was introduced a new funding channel to finance political parties in India in 2017 Finance Bill. The same was notified by the Ministry of Finance on January 2, 2018. The Union Budget 2017 which devoted a full section on electoral reforms particularly new channels of political funding, introduced the novel bonds scheme to check rampant “under-the-table cash transactions”. The key purpose as shared by the government (Finance Minister Arun Jaitley) was to infuse political system with “white money”. Post-demonetization drive in November 2016, this new instrument was singled out as key weapon to fight the menace of black money.

What is an electoral bond? An electoral bond is a bearer instrument in the manner of a promissory note. It is an interest free banking instrument whereby a citizen, or a business entity in India is eligible to purchase (either through cheque or digital payments) the bond from specific branches of the State Bank of India for 10 days each in months of January, April, July and October. As per the business rules unveiled by the government in 2018, EB can be purchased by a person, who is a citizen of India or incorporated or established in India. Further, a person being an individual can buy electoral bonds, either singly or jointly with other individuals. Only political parties registered under Section 29A of the Representation of the People Act, 1951 that has secured not less than 1 per cent of votes polled in the last general election to the House of the People or the Legislative Assembly of the State is eligible to receive such donations.

Other highlights of EB are that the bonds will be valid for 15 days only and shall not carry the donor's name, although the payee will have to fulfil KYC (Know Your Customer) norms at the bank. What is important here is no report is required to be submitted by receiving parties in case of donations received via electoral bonds. In other words, neither donors nor political parties are legally bounded to reveal the details of donations. Thus, opacity is ingrained with this new instrument for political funding.

What is wrong with Electoral Bonds?

While there is some merits in having electoral bonds to infuse political system with “clean money” as the buyers of the bonds will have to furnish KYC in the authorised bank and do the transactions either through cheque or digital means, the anonymity clause for donor and political parties make it half attempt. Fact of the matter is anonymity clause or lack of disclosure requirements for the individuals or corporate donors buying such bonds defeats the fundamental principle of transparency in political finance. In fact, as the global evidence of political finance say opacity in donation would make it a convenient channel for black money flow. To expand the argument further, EB could be convenient channel for business to round-trip their cash parked in tax havens to political parties for quid pro quo. Yet, what makes the scheme even more controversial is the removal of 7.5% cap on corporate donations (bringing changes in the Companies Bill 2013). This would allow for unlimited corporate/businesses donations even from the loss making companies.

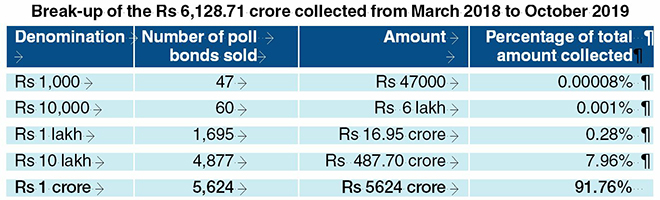

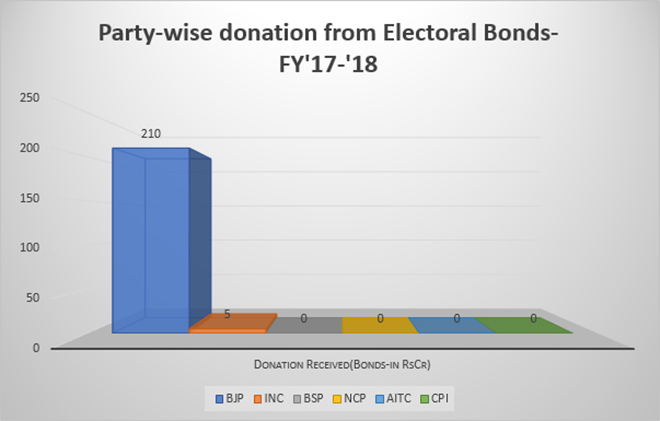

Similarly, given the fact that a public sector bank will be sole repository of donor details, in effect the government of the day (given it is a public sector bank, the Ministry of Finance (and the government of the day) will automatically have an upper hand on this new mode of donations. This is clearly evident from the early trends of donations. For instance, from seven tranche of bonds that were rolled out in March 2018, the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party received a mammoth 94.5% of total donations via bonds route (see chart 1).

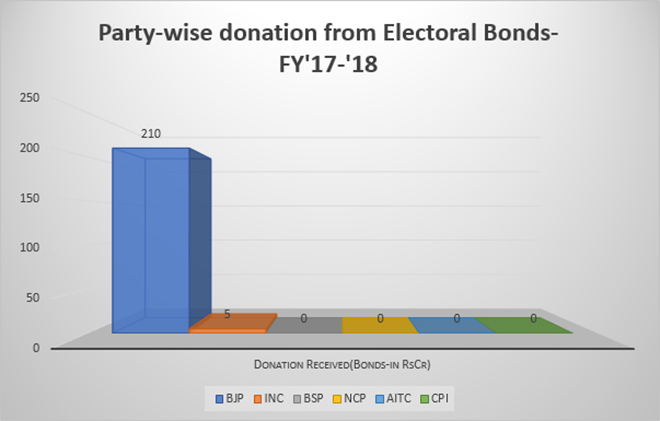

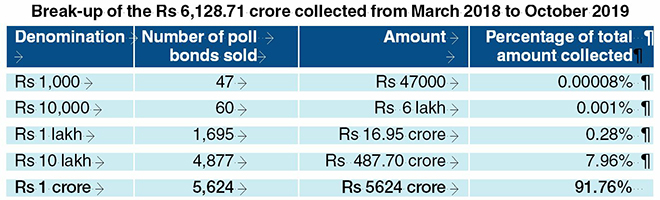

Table 1. Total Donations via Electoral Bonds (March 2018-October 2019)

Source: The Telegraph

Source: The Telegraph

However, the far bigger challenge emerging from this novel scheme is, that it would bring invite unchecked influence into political system via big donations. With its anonymity provision, it is likely to attract corporate and wealthy donors to opt for this route as it protects their identities. If the early trends of donations are to be believed (with 90% donors donating above 1 million) electoral bonds is bringing unbridled corporate influence into politics and governance of the country. In effect, the government has legalised crony-capitalism into country’s democratic system. The consequences of a cosy business-politics nexus are well known.

To conclude, the early trends as revealed from RTI information and quantum of donations (Rs 6128 crore in just 18 months) flowing via this channel point to very serious challenge facing India’s electoral democracy and nature of politics. In short, electoral bonds along with corresponding changes that the government introduced in 2017 Finance Bill particularly the removal of 7.5% cap in corporate donations undo the significant gains achieved in political finance reforms and transparency norms. One hopes the Supreme Court when it takes up the pending petition will make a thorough audit from the standpoint of transparency and fairness to strengthen country’s fragile campaign finance regime.

Chart 1: EBS Donations to Political Parties

Source: Computed from ADR Data (based on March 2018 tranche)

Source: Computed from ADR Data (based on March 2018 tranche)

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source: The Telegraph

Source: The Telegraph Source: Computed from ADR Data (based on March 2018 tranche)

Source: Computed from ADR Data (based on March 2018 tranche) PREV

PREV