-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Amid rising debt, government bets that big infrastructure spending is not just growth-enhancing, but also popular

This brief is a part of the Budget 2022: Numbers and Beyond series.

Finance Minister, Nirmala Sitharaman, in designing the Union Budget for 2022-23, had just one piece of good luck to balance multiple problems. The good luck was that tax revenue in the past year was unexpectedly buoyant: The Union got 14.2 percent more in taxes over 2021-22 than she had budgeted for last February. This meant that she could make relatively conservative assumptions about how much tax revenue would grow in the coming year, and still make her fiscal maths add up; and that the fiscal deficit in the past year, at 6.9 percent, only narrowly missed her target of 6.8 percent.

A combination of more debt and higher yields is deeply uncomfortable, as both of those drive up the amount that the government has to spend in interest payments.

But red abounds on the other side of the ledger. The effects of the pandemic are now clearly visible. Private investment and, thus, growth is yet to rebound, so the government feels it must continue to focus on “priming the pump”—pouring its resources into investment, in the hope that the private sector will respond positively. Meanwhile, the debt it began to take on starting in the pandemic year is beginning to tell. India is now a high-debt economy for the first time since independence; its national balance sheet has a financial profile reminiscent of improvident Latin American countries with oversized welfare states, and not a lean, sleek Asian tiger. As debt increases without a growth spike, so do—usually—the yields on the bonds the government takes out to finance its deficit; yields in India’s headline 10-year bond jumped in response to the news that the finance ministry would have to raise an unprecedented amount from the market. A combination of more debt and higher yields is deeply uncomfortable, as both of those drive up the amount that the government has to spend in interest payments. And those have indeed been increasing sharply; over the coming year, the government will pay out 38 percent more in interest than it did in 2020-21. Its interest payments are almost 24 percent of its budget, 3.5 percentage points higher than prior to the pandemic. They are approaching 50 percent of the Union’s tax revenue.

A government that prioritises fiscal prudence, as this one traditionally has, would respond to this problem by squeezing spending. And, indeed, that is what Ms Sitharaman has done in part. In fact, the coming year, if all goes to plan, will see the sort of squeezing of current expenditure that is usually only seen in countries undergoing structural adjustment programmes. When you take out interest payments and its spending on capital assets, expenditure on the Union’s revenue account will shrink almost 30 percent in 2022-23. Some of that will come from a prompt withdrawal of extra subsidies set aside for pandemic relief—for example, additional food rations. But it is clear that the Finance Minister has even otherwise made a Herculean effort to control revenue expenditure.

A government that prioritises fiscal prudence, as this one traditionally has, would respond to this problem by squeezing spending.

Usually that means that growth is going to suffer. And, indeed, we should worry about India’s growth engine going forward—especially in the absence of private investment and ever larger flows of global capital. But the Finance Minister has not given up on growth. She’s poured the minimal resources at her command into an unprecedented surge in infrastructure and other capital spending.

This is a risk. Previous attempts to use the exchequer to galvanise the private sector into investing haven’t worked out for the government.

Does this mean that the welfarist populism that many political scientists argue has aided Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s electoral popularity in recent years has ended? Has the government moved to a straightforward, supply-side formula? No, for two reasons.

Ever since about the 2004 general election, the conventional wisdom is that governments are judged on “Bijli, sadak, paani”—power, roads, and water.

First, the government’s faith in the Indian state remains undented. Yes, there is an increased understanding that growth will not happen without private capital—and indeed without global capital. But the state will remain very much the senior partner in this co-operation. It will direct the sectors where capital should flow, it will choose the partners it supports, and it will determine the pace of their investment.

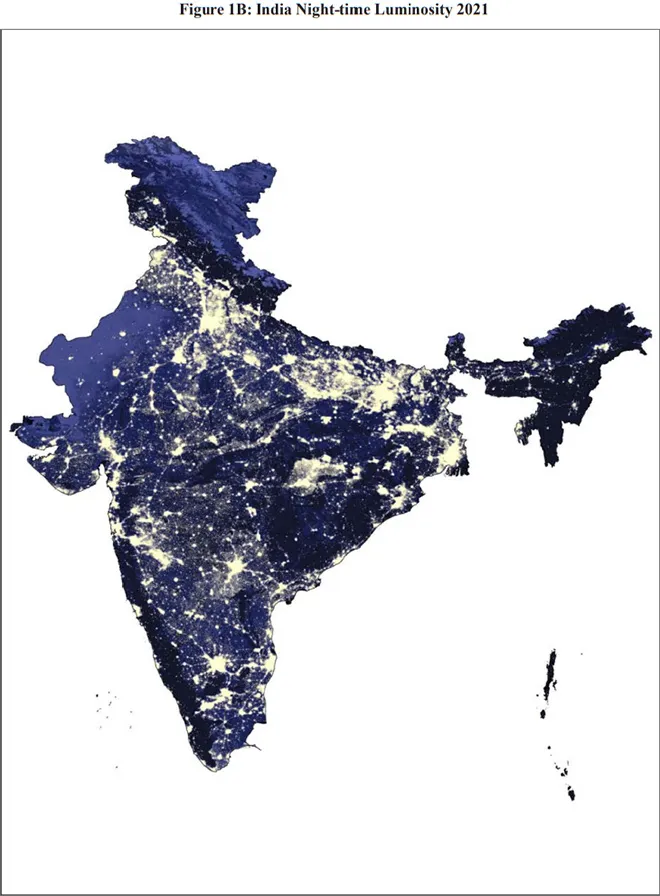

Second, the notion that subsidies are welfarist while infrastructure is not is, frankly, wrong-headed. What are governments in this country supposed to do? Ever since about the 2004 general election, the conventional wisdom is that governments are judged on “Bijli, sadak, paani”—power, roads, and water. What are these, if not infrastructure sectors? Electrification has been vastly advanced in this country over the past decade, as a startling photo of night-time luminosity in the Economic Survey pointed out; the Budget promised that the pace of road-building would increase manifold to 68 kilometres of highway a day, with the National Highways Authority of India pulling in almost three times as much budgetary support as it did in 2020-21; and delivering safe drinking water is the landmark promise of Mr Modi’s second term, just as electrification was for his first. The Jal Jeevan Mission has been given INR 60,000 crore in the Budget, almost six times as much as 2020-21.

Source: Economic Survey 2021–2022

Source: Economic Survey 2021–2022

This Budget has made something clear about how the government thinks, and its big bet. It has bet that big infrastructure spending is not just growth-enhancing, but also popular. We cannot be certain how this will turn out, but what is certain is that, faced with a crushing debt burden, an inflationary environment, and underperforming taxes, Ms Sitharaman has somehow delivered a Bijli-Sadak-Paani budget.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Mihir Swarup Sharma is the Director Centre for Economy and Growth Programme at the Observer Research Foundation. He was trained as an economist and political scientist ...

Read More +