-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

As naval power becomes central to great-power competition, India must build a renaissance navy capable of deterring China and shaping the future balance of power across the Indo-Pacific

The great American strategist Andrew Marshal, who ran the Office of Net Assessment in the Pentagon for close to half a century, insisted that strategy could only be formulated by first defining the scenario to be tackled. The overwhelming geopolitical scenario that dominates all discussion today is the likely outcome of the strategic competition between the US, the current hegemon, and China, the aspiring leader of the world. How would the geopolitical landscape of Eurasia, Africa, the Indian Ocean, and the Atlantic littoral look if the hegemon were displaced? The tip of the iceberg is that today, US$10 trillion separates the GDPs of the US (US$29 trillion) and China (US$19 trillion). Most major economic forecasters, including Goldman Sachs, McKinsey & Company, and PricewaterhouseCoopers, predict that by 2050, China will have roughly a US$10 trillion lead over the US, with India trailing the US figure by another US$10 trillion.

GDP, of course, is only a coarse indication of the myriad factors that constitute this competition, which broadly include economic, technological and educational capabilities, military and space power, geopolitical influence and global governance roles, as well as social and cultural drivers. Currently, the results of each of these competitions seem to indicate a close finish. For instance, the US lead in AI, quantum computing and space, with a stranglehold on chips, appears to be matched by China’s lead in engineering, research papers and citations, as well as research funding, which has recently been gutted in the US by President Donald Trump. For us in India, the military, space, and geopolitical domains — particularly the capture of world governance — are the most critical factors.

China has a Grand Strategy, broadly referred to as the ‘Chinese Dream,’ under which various white papers and party plenums outline separate silos for economic development, technological supremacy, improving living standards, social welfare, and, finally — what concerns us most — military rejuvenation.

To examine these factors, it would be prudent to see what China considers essential for achieving victory in these areas. For instance, China has a Grand Strategy, broadly referred to as the ‘Chinese Dream,’ under which various white papers and party plenums outline separate silos for economic development, technological supremacy, improving living standards, social welfare, and, finally — what concerns us most — military rejuvenation. Although Beijing does not publish the service-wise distribution of its defence budget, an artificial intelligence study initiated by this author indicates that, of the total budget on military hardware, the PLA Navy receives 70 percent.

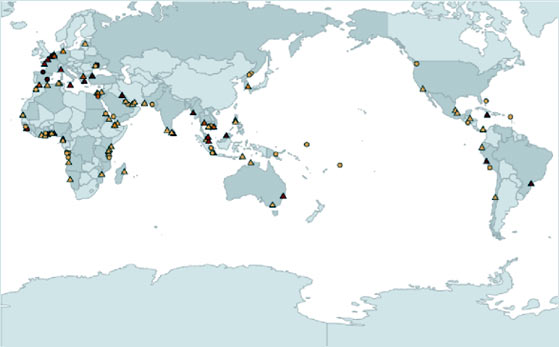

Beijing’s geopolitical ambitions include becoming the manufacturer to the world and the prime trading partner — envisaging a mercantile sweep through the Indian Ocean into Europe and beyond Africa, across the Atlantic into South and Central America, including Panama. Thus, the four ports built in the Indian Ocean that we are familiar with — in Chittagong, Sittwe, Hambantota, and Gwadar — are just the beginning of Beijing’s broader plan to dominate the world’s oceans, as shown below.

129 Chinese-Owned Ports

Source: Council on Foreign Relations

Clearly, New Delhi needs to respond with a matching Grand Strategy, which may or may not emerge from South Block. Navies, however, take at least 30 years to develop, and naval thinkers must craft a response immediately. Beijing has historically thought in terms of a hundred-year competition, the origins of which, in the India-China context, can be traced to 1980 with the deliberate arming of Pakistan with nuclear weapons — enabling Islamabad to field an air-deliverable bomb in 1987, eleven years before Pokhran. The consequences of a hegemonic China, deeply hostile to India and dominating Asia, are particularly grim for New Delhi. Militarily, this competition (not overt hostilities) will not be won on the Himalayan frontier, where the geography is deeply unfavourable to India.

Beijing’s anxieties — and its only real weakness — can be exploited by India primarily in the Indian Ocean by threatening to interrupt its expansive westward sweep, leveraging the favourable geography of the Malacca Strait and the tyranny of distance.

Beijing’s anxieties — and its only real weakness — can be exploited by India primarily in the Indian Ocean by threatening to interrupt its expansive westward sweep, leveraging the favourable geography of the Malacca Strait and the tyranny of distance. Of all the services, the Navy is the most self-reliant, albeit technology-heavy. How, then, can we harness our impressive naval architectural skills and the engineering capacities of our shipyards to create a renaissance Navy over the next 25 years? Our response must combine the best of technology with a coherent winning strategy.

The most decisive result of technology and the domination of near space on future warfare is that all countries have become exposed and transparent to a resolution of 10 centimetres. A medium-sized country like Pakistan, therefore, generates roughly 5,000 targets, the destruction of which will take it back to the Stone Age. China probably generates 20,000 targets. Along with this is the decisiveness of the sea-based land-attack cruise missile, which gives navies the capacity to go beyond attacking enemy fleets to attacking their homeland.

During the last 30 years, the course of world history has been significantly influenced by the US Navy firing 2,300 Tomahawks. The strength of navies is measured not by the number of warships, but by the number of Vertical Launch Silos (VLS) they can muster; the US Navy currently fields 9,900 and the PLAN, 4,200. We can aspire to a number not less than 4,000 by 2050 if we build 30 of the Type 18 destroyers, currently being built in Mazagon, and launch a 24-SSN (attack submarine) programme, each carrying 24 VLS (3,000 + 1,000). The Type 18 destroyer, a formidable platform, has 144 VLS cells, of which a hundred may be allocated for the Land Attack Cruise Missile. China has also developed a formidable Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) capacity in the South China Sea up to the Second Island Chain, but this is penetrable by an SSN fleet. Our SSN deployment would bring under threat the densely populated and heavily industrialised sections of southeast China.

The strength of navies is measured not by the number of warships, but by the number of Vertical Launch Silos (VLS) they can muster; the US Navy currently fields 9,900 and the PLAN, 4,200. We can aspire to a number not less than 4,000 by 2050 if we build 30 of the Type 18 destroyers, currently being built in Mazagon, and launch a 24-SSN (attack submarine) programme, each carrying 24 VLS (3,000 + 1,000).

Lastly, the domination of the Indian Ocean’s surface — carrying around 60 percent of China’s energy and 80 percent of its foreign trade — will require India to deploy three large aircraft carriers of not less than 80,000 tons to dominate the entire ocean battlespace up to the troposphere. Our capabilities must act as a conventional deterrent and enable New Delhi to follow a policy of strategic autonomy.

K. Raja Menon previously served as the Assistant Chief of Naval Staff (Operations) in the Indian Navy.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Rear Admiral K. Raja Menon (Retd) is a career naval officer and submarine specialist who commanded seven ships and submarines during his service. He retired ...

Read More +