-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

In addition to the fears of surviving this pandemic, citizens of West Bengal have to unfortunately cater to an additional anxiety resulting from — the reportedly dubious coronavirus statistics laid out by the state and some untimely political measures taken by the Centre to deal with the situation.

The beginning of the COVID-19 scare in India, in February this year, was worrisome for the state of West Bengal. This was mainly because statistics showed the healthcare facilities in West Bengal not at par with that of Maharashtra and Kerala. In both these states, the situation had been on the verge of going out-of-hand in the initial days. According to the parameters of Sustainable Development Goal 3 (Good Health and Well Being) estimated by NITI Aayog’s SDG India Index 2019-2020, West Bengal scores 70 (out of 100) in comparison to Maharashtra’s 76 and Kerala’s highest score of 82. In fact, the concentration of medical facilities in Kolkata as opposed to rural Bengal made the access to healthcare infrastructure a major problem for a large majority of the state’s population. Additionally, the proximity of state of West Bengal with various international borders along with the developments of Bengali migrant labourers being sent back from the other states to their home state contributed in making the situation worse.

The first coronavirus positive case in West Bengal was in Kolkata of an 18-year-old man who returned from the UK. It created quite a furore in the political circles of the state when this man was found to be the son of a senior state government official, who claimed to have flouted the quarantine rules and even visited the West Bengal State Secretariat after his return. However, this was just the beginning of the political mess that the state would run into in the next few weeks.

Simultaneously, the state government also has been exceptionally proactive in taking a lot of measures which included the early-on reduced activity in the state much before the nationwide lockdown which started on 25 March 2020, the 200-crore state relief fund to tackle the crisis, distribution of mid-day meals in bulk, making the public distribution system free, and finally, sending letters to 18 chief ministers across India for a coordinated mechanism to rescue migrants across the country.

Amidst all these, although measures such as opening of 27 night shelters in Kolkata for stranded migrants and strict instructions to employers for not deducting wages were lauded, a large part of the migrant distress — especially in rural Bengal — remained substantially under-reported. However, the issue of under-reporting of facts took a whole new dimension as the controversy regarding the coronavirus statistics surfaced in the state. All of this gained momentum as a group of non-resident medical professionals recently wrote an open letter to the West Bengal Chief Minister regarding the ‘gross under-testing’ and ‘misreporting of data’ related to COVID-19 deaths in the state. Further suspicions were raised when the letter mentioned how “only a state-appointed committee is allowed to declare if a patient has died from COVID-19.” This further signaled towards data suppression allegations when the same government has been accused of notoriously suppressing data related to dengue outbreak in the past as well.

As of 25 April, national level statistics shows that West Bengal has conducted approximately 100 tests per million which is one of the lowest among the major Indian states. Out of these tests, 5.8 percent were COVID-19 positive patients, ranking behind Maharashtra, Delhi and Gujarat. The state government however clarified that not only were the necessary clearances for setting up additional testing centres given on time, but also, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) failed to provide functional test kits to West Bengal.

The ICMR later admitted that the Bengal test kits were indeed faulty and asked the state to return all the rapid testing kits on 27 April. Reports suggest, almost 10 percent of the infected patients account for COVID-19 deaths in this eastern state which is almost three times the national death rate due to coronavirus infection. However, official government reports pegged the death figure to a mere 22 as of 30 April, by excluding patients who died from co-morbidities.

A recent on-ground report from the four main government hospital in Kolkata for coronavirus treatment — ID & BG Hospital, MR Bangur Hospital, Sagore Dutta Hospital, RG Kar Medical College — suggests the sorry state of health infrastructure along with lack of transparency in these facilities. Detailed interviews with a wide variety of doctors, nurses and other medical staff depict a frightening picture in terms of inadequate manpower and medical training, lack of Personal Protective Equipments (PPEs), anomaly over death certificates due to insufficient clarity on the reason of death, ‘COVID pregnancies’, etc. The current scenario in these hospitals reaffirms the concerns over the safety of healthcare workers and the fate of non-COVID patients across the country.

Under such adverse circumstances, a few political developments in the state have been quite unfortunate as well. These include:

• The tussle between the state government and the Union Ministry of Home Affairs over sending central COVID-19 teams to the state for monitoring purposes, which led to both sides sending out lessons of India’s federalistic governance structure to each other.

• The bitter exchange of letters between the Chief Minister and the Governor of West Bengal after the latter repeatedly complained regarding the relief measures and the handling of the healthcare situation in the state.

• The Chief Minister also launched a scathing attack on the central government for mishandling the Tablighi Jamaat incident and adding communal colours to it — the state government quarantined 177 people who attended the congregation.

• And finally, yet another incident of mob violence against police personnel took place in Tikiapara, in Howrah district when the West Bengal police force was trying to enforce a lockdown in the red zone region. This was followed by a political scuffle between TMC and BJP at the local levels.

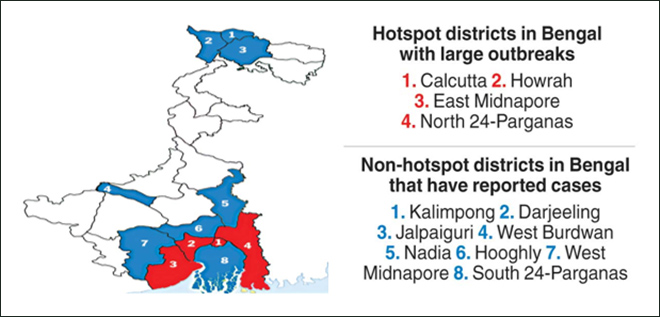

The following figure shows how the Union Health Ministry had demarcated Kolkata and the nearby hubs (including Howrah district) as coronavirus hotspots in the state, earlier in the month of April.

Source: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, GOI

Source: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, GOIIn conclusion, it must be noted that in addition to the fears of surviving this pandemic, citizens of West Bengal have to unfortunately cater to an additional anxiety resulting from — the reportedly dubious coronavirus statistics laid out by the state and some untimely political measures taken by the Centre to deal with the situation. As the Kolkata figures for COVID-19 positive cases reaches 184 and the West Bengal figure reaches 758, as of April 30, the complex dynamics between the state and the Centre in the middle of this crisis is a matter of great concern.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Soumya Bhowmick is a Fellow and Lead, World Economies and Sustainability at the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy (CNED) at Observer Research Foundation (ORF). He ...

Read More +