-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The impact of COVID-19 has shown that Spain, like many other countries, must work hard on improving its internal capability to manage pandemics.

COVID-19 has hit Spain particularly hard. The first wave of the virus, suffered in late winter and spring 2020, was one of the worst in the European Union (EU), requiring a strict stay-at-home lockdown of over 100 days between 15 March and 21 June. Banning mobility affected the Spanish economy since it is one of the most open countries in the world, receiving, on average, over 80 million visitors every year. Tourism accounts for 12 percent of GDP and 13 percent of employment. This structural factor partly explains the steep decline of 18.5 percent of GDP in the second quarter of 2020, way above the EU GDP, which contracted by “only” 11.7 percent. <1>

The situation remains dire. Annual GDP contraction <2> for 2020 will be around 12 percent, the deepest since the Civil War in the 1930s. The fiscal deficit will be north of 10 percent, and unemployment will be close to 20 percent. More worrying, the health situation is worsening, with the threat of a second wave at the end of the summer and beginning of autumn looming. At the end of August, with over 3,000 new cases every day, Spain has the highest incidence of COVID-19 in Western Europe. Spain’s numbers are currently three times higher than those of Italy, which had a similar trajectory during the first wave. Spanish experts and researchers are still trying to explain why Spain is such an outlier in Europe and why there is such a difference with Italy, a similar country geographically and culturally.

"Spain’s numbers are currently three times higher than those of Italy, which had a similar trajectory during the first wave."

There are multiple possible factors. Perhaps Spain is testing more than Italy, but it can also be that the Spanish lifestyle, <3> especially during the summer, is more prone to contagion. Furthermore, quickly opening all businesses in June for the summer season to attract tourists was a national urgency. In hindsight, it might have been a mistake to open bars, clubs and discotheques until late hours. Italy has not allowed that and has maintained its state of emergency to impose targeted lockdowns. It appears that Italy has better tracing capacities than Spain, which still has relatively low ratios of trackers per 1000 people in most of its autonomous regions.

According to the information reported by individual countries, <4> Spain, the 30th largest country in the world in terms of population, currently ranks ninth in terms of absolute number of cases, as of 4 September. While it is imperative to view these statistics with consummate care, both because of the scant transparency shown by some countries and because of the objective counting difficulties associated with an illness where a considerable proportion of infected patients are asymptomatic, there can be little doubt that Spain is at the forefront of COVID-19 incidence, at least in Europe, and this is also confirmed by the first studies into seroprevalence <5> (level of a pathogen in a population measured in blood serum) where, in theory, problems of undercounting are avoided.

The questions and lack of homogeneity regarding official information also arise when one turns to the number of deaths, a statistic that has understandably been viewed as more important for determining the real impact of the disease. According to the official figures at the time of writing, <6> Spain ranks eighth in the world in terms of the absolute number of deaths (below seven more populous countries — the US, Brazil, Mexico, India, UK, Italy and France). When the ranking is carried out relative to population size, and once micro-countries have been removed, Spain is ranked only behind Belgium and Peru in mortality, with similar numbers to those of the UK.

"What are the reasons for such a high ranking in the number of cases and deaths?"

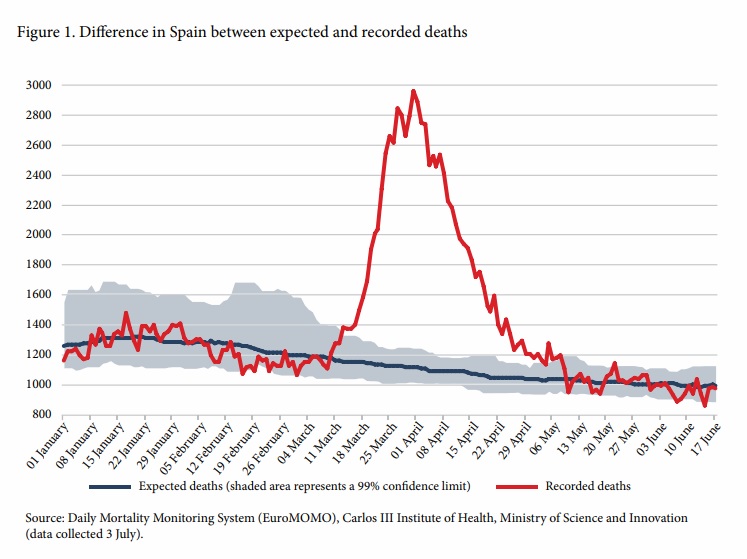

As with the number of cases, the difficulties in gathering information cast doubts on the reliability of the international comparison of mortality rates. An alternative measurement to the official figures consists of taking, as a proxy indicator, the difference between the total deaths recorded and those expected based on historical trends for the same period. In this case, for Spain, in the period from March to August 2020, about 29,000 deaths were certified as owing to COVID-19. In contrast, the monitoring system of the Carlos III Health Institute recorded 43,000 excess deaths, which the National Statistics Institute raised to 48,000 (see Figure 1). This means that Spain currently has the most excess deaths in Western Europe. <7> Hence, the question remains, what are the reasons for such a high ranking in the number of cases and deaths?

There are various factors that account for the spread of the virus, the most prominent being population density and high mobility. This would explain the lower incidence of the disease in countries with low population densities and fewer travel links to territories where outbreaks have occurred and greater transmission in large cities with significant foreign travel flows, densely occupied housing and congested public transport networks. Spain has one of the largest urban population concentrations in Western Europe; its 47 million inhabitants live in 13 percent of the country’s territory. <8> It is no coincidence that, according to the excess deaths figures available, among the areas most affected are New York (with an excess death rate of 208 percent) and the main globalised metropolitan areas of Western Europe, including Madrid (157 percent) and Catalonia (106 percent). <9> Moreover, Madrid and Barcelona are not only highly interconnected with the world, but also with the rest of Spain, which would have contributed to spreading the disease around the country.

"It is no coincidence that, according to the excess deaths figures available, among the areas most affected are New York (with an excess death rate of 208 percent) and the main globalised metropolitan areas of Western Europe, including Madrid (157 percent) and Catalonia (106 percent)."

Another important factor seems to be everything related to forms of socialisation. Some countries habitually maintain an interpersonal distance of more than 1.5 metres (since getting closer than this is considered as intrusive). In others such as Spain, however, there is a tendency towards physical proximity and greetings that involve contact between hands, faces and bodies.

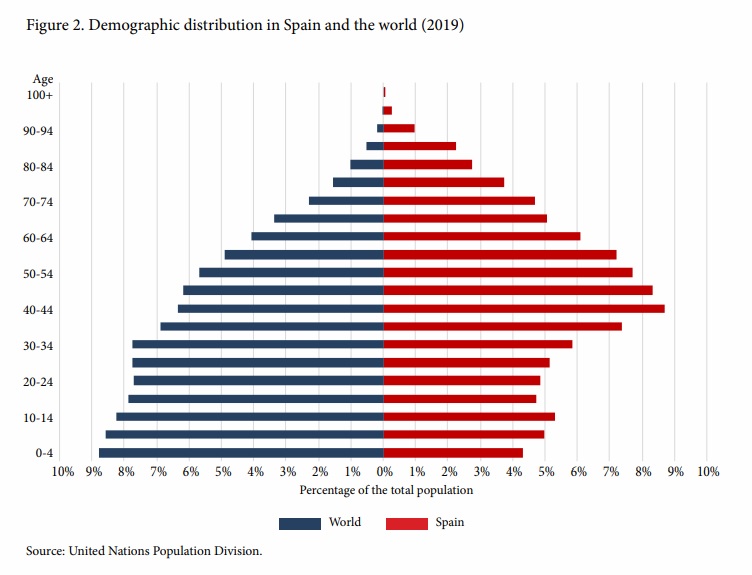

The age distribution is another decisive factor in the incidence of COVID-19. Not only are there fewer infections among children and young people, but mortality rises steeply among older people. This factor puts Spain at a disadvantage since it is one of the most aged countries in the world (see Figure 2) where close daily intergenerational contact prevails, even if elderly relative lives in care homes.

Thus, the countries most affected ought to be those that are most aged, with large, densely populated urban areas and highly mobile inhabitants, and exhibiting social conduct based on physical proximity. This pattern is applicable to Spain and the other Western European countries with high infection rates, but it is not consistently confirmed elsewhere. Japan, the most aged country in the world, with a high population density and great interconnectedness with China (the original source of the pandemic), has recorded very few deaths. And while cultural social distancing, the widespread use of masks and mobile phone applications have served as protective measures in East Asian countries, it is likely that there are additional elements that need to be borne in mind. The earliest scientific studies put forward conjectures such as the climate, pollution, the diversity of virus strains, the possibility of greater propagation and mortality due to genetic susceptibility, and even the volume and intensity of speech (generally high in Spain) having a bearing on the rate at which the virus spreads. <10>

"There have already been some attempts to compare and evaluate countries’ management efforts, but these have been superficial and have failed to take into account the complexity of the various factors contributing to the spread and mortality of a virus."

Among these other factors is the key issue of the response of the public health service and the national healthcare capabilities. There have already been some attempts to compare and evaluate countries’ management efforts, <11> but these have been superficial and have failed to take into account the complexity of the various factors contributing to the spread and mortality of a virus. Without isolating the structural causes set out above, an attempt to measure national management will tend to take the dependent variable — the number of deaths — as the main supposedly explanatory indicator and, therefore, the Western European countries that recorded the most deaths in the first wave (Belgium, Spain, Italy and the UK) appear in the final places in these initial indices.

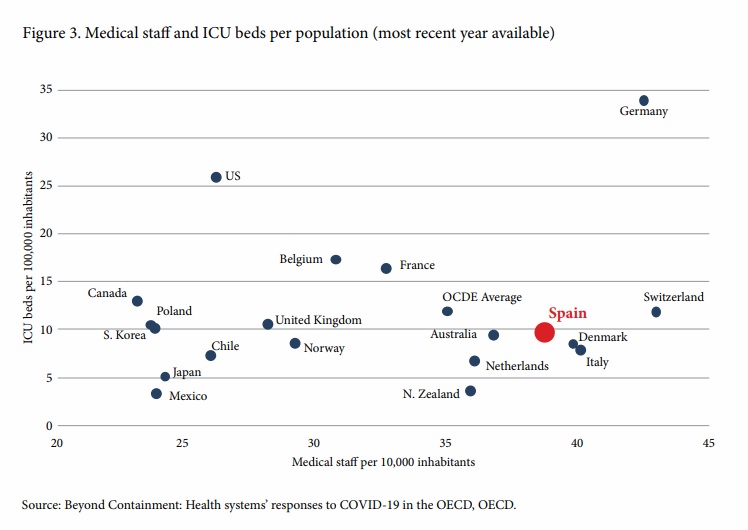

Despite the fall in public spending on health since the Great Recession, the Spanish health system continues to occupy a mid to high position in comparative rankings. In some indicators, such as medical staff per inhabitant, it emerges better than in others, such as the low number of nursing staff and beds, although the number of ICU beds is around the OECD average (see Figure 3).

Nevertheless, COVID-19 has revealed the weaknesses of the healthcare system, both in terms of public health policy and patient care.

The system is designed in a relatively efficient way to offer primary care, treat common illnesses and deal with epidemics like those already known. But Spain (which, like the rest of Europe, had not suffered either SARS or MERS) had neither the experience nor enough resources to prevent, detect or deal with a pandemic of this nature, despite the fact that the current National Security Strategy has been vainly warning of this threat since 2017. <12> This highlights the shortcomings in public health, which include the need to improve handwashing culture among the general public and even among health professionals, <13> and at least two striking aspects of patient care — the sorry situation in many old peoples’ homes (where approximately half of COVID-19 victims may have died), and the lack of adequate personal protective equipment for health workers, which led to a large number of infections.

Numerous epidemiologists have been denouncing the cuts inflicted on the system, <14> and the consequent lack of human and material resources. The public health apparatus, including the Coordination Centre for Health Emergencies and Alerts, which has led the management of the crisis, currently accounts for only one percent of the health budget. Given recent events, this figure explains the shortcomings, ranging from the collection of data, including tracing capabilities, to the shortage of ventilators and testing units.

"The public health apparatus, including the Coordination Centre for Health Emergencies and Alerts, which has led the management of the crisis, currently accounts for only one percent of the health budget."

In terms of governance, another widespread problem in Europe has been a lack of coordination, whether among experts and decision-makers or among the various agencies and levels of administration. In Spain, a range of managerial failings has been identified between the central government and the autonomous communities (regions), including the lack of reliable and homogeneous data identified by the National Network of Public Health Surveillance.

On the other hand, certain circumstances can be viewed as strengths since they have aided Spain’s response capability for dealing with the health crisis.

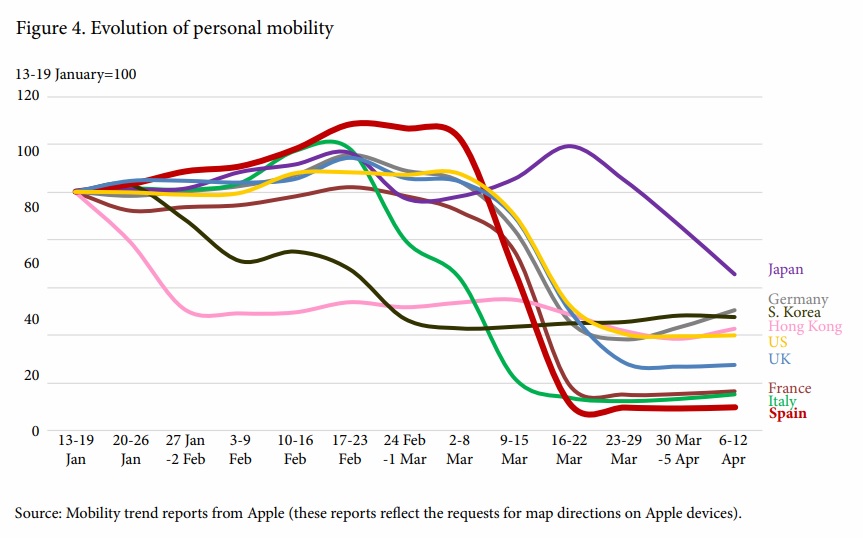

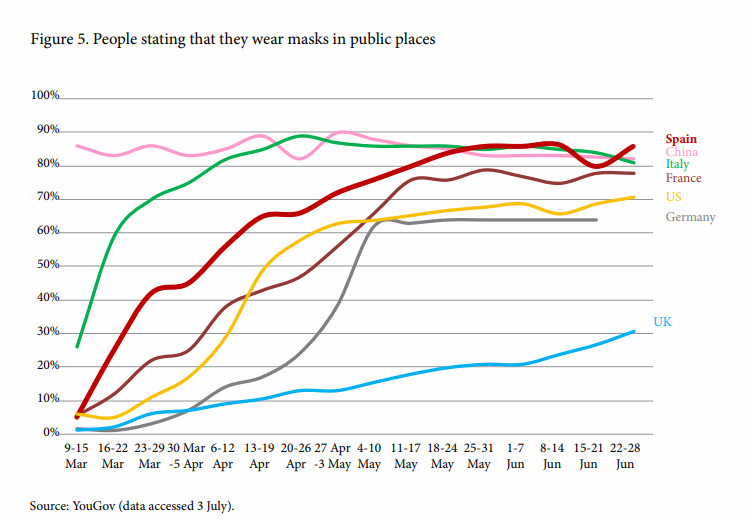

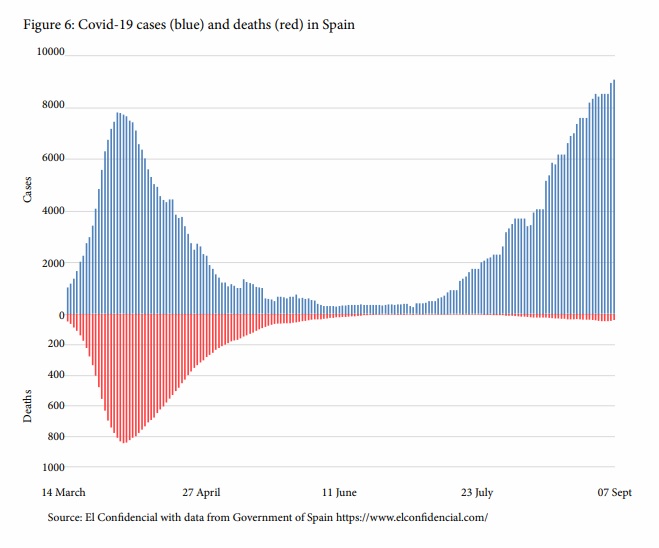

Leaving aside the debate about the possible delay in imposing restrictions on mobility and announcing the lockdown in March, the strict degree of compliance with the quarantine and the use of masks (see figures 4 and 5) as well as their effectiveness in flattening the infection curve during the lockdown is undeniable. The Spanish public has displayed remarkable discipline and civic responsibility, particularly considering that it was one of the strictest in Europe (and therefore not without controversy). Unfortunately, some of this discipline is being lost during the summer, and Spain is experiencing a strong rebound in cases since early July, even if it has only brought a minor increase of daily deaths (see figure 6).

This second wave of contagion during the summer months does not mean that the Spanish population will not be able to maintain social distancing again after the holidays are over. About 97 percent of the Spanish public surveyed in April, when the lockdown was at its strictest, viewed the measures taken to combat the pandemic as “necessary” or “very necessary,” while 91 percent stated they were experiencing a “very good” or “reasonably good” lockdown, partly thanks to the excellent high-speed internet connectivity that the country has. <15> This attitude is important for maintaining social distancing measures and even, if the epidemiological situation requires it, returning to lockdown.

"About 97 percent of the Spanish public surveyed in April, when the lockdown was at its strictest, viewed the measures taken to combat the pandemic as “necessary” or “very necessary,” while 91 percent stated they were experiencing a “very good” or “reasonably good” lockdown, partly thanks to the excellent high-speed internet connectivity that the country has."

Despite the stressful situations that have been endured and the manner in which some hospitals were overwhelmed in Madrid and Barcelona, where half of Spain’s deaths occurred, the health system and other public services did not break down in other parts of the country. In general, there has been medical staff and other public employees who have shown exemplary professionalism, proving capable of adapting their work , with a certain degree of improvisation, to the state of alarm applied for the first time in a general and prolonged way. The Spanish state has also been able to fund a massive short-term work programme for workers and guarantee a loans programme for enterprises to cushion the severity of the economic crisis.

The impact of COVID-19 has shown that Spain, like many other countries, must work hard on improving its internal capability to manage pandemics. Apart from the specific mistakes, which are subject to the healthy accountability that is the hallmark of a democracy, the errors of forecasting and reaction, which for some have constituted a failure and for others are understandable given that we are facing the greatest pandemic of the last 100 years, are not really the fault of an individual government at a particular moment in time. Instead, the lack of preparation of the State itself has been revealed, including not only public authorities (which naturally bear the brunt of responsibility) but also members of the public themselves. Learning the lessons of this crisis for the future should, therefore, involve paying attention to the following issues:

This essay originally appeared in Rebooting the World

<1> “GDP down by 12.1% and employment down by 2.8% in the euro area”, Eurostat, August 14, 2020.

<2> “Macroeconomic Projections for the Spanish Economy (2020-2022)”, Banco de España.

<3> Daniel Dombey, “Socialising pushes Spain´s Covid-19 rate far above rest of Europe”, Financial Times, August 21, 2020.

<4> “Covid-19 Global Overview. Distribution of cumulative confirmed cases”, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

<5> Marina Pollán et al., “Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in Spain (ENE-COVID): a nationwide, population-based seroepidemiological study”, The Lancet 396 (10250): 535-544 (2020).

<6> “Reported Cases and Deaths by Country, Territory, or Conveyance”, Worldometers.

<7> “Coronavirus tracked: the latest figures as countries fight Covid-19 resurgence”, Financial Times, September 2, 2020.

<8> Esteban Ramón, “La anomalía española: combatir la covid-19 con la 'mayor densidad de población' de Europa”, RTVE, September 4, 2020.

<9> “Coronavirus tracked: the latest figures as countries fight Covid-19 resurgence”, Financial Times, September 2, 2020.

<10> Kai Kupferschmidt, “Why do some COVID-19 patients infect many others, whereas most don´t spread the virus at all?”, Science, May 19, 2020.

<11> “Quality of OECD countries´ response to the pandemic”, The Economist Intelligence Unit.

<12> Department of Homeland Security, Government of Spain, “National Security Strategy 2017”, December 2017.

<13> Ganna Pogrebna et al., “The Impact of Cross-Cultural Differences in Hand washing Patterns on the COVID-19 Outbreak Magnitude”, preprint (2020).

<14> Irene Hernández, “Esta pandemia se está instrumentalizando políticamente, especialmente en Cataluña” (interview with epidemiologist Miquel Porta), El Mundo, April 9, 2020.

<15> Enrique Medina, “Why Spain is a case study for super-fast broadband: Telefónica”, ITUNews, November 27, 2017.

<16> Fiona Govan, “Radar Covid: What you need to know about the app Spain says you ´must´ download”, The Local, August 29, 2020.

<17> Jonathan Hackenbroich, Jeremy Shapiro and Tara Varma, Health Sovereignty: How to Build a Resilient European Response to Pandemics, European Council on Foreign Relations, 2020.

<18> Olivier Blanchard, Thomas Philippon and Jean Pisani-Ferry, A New Policy Toolkit Is Needed as Countries Exit COVID-19 Lockdowns, Washington DC, Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2020.

<19> Federico Steinberg, Miguel Otero Iglesias and Enrique Feás, ¿Recuperación o metamorfosis? Un plan de transformación económica para España, Madrid, Real Instituto Elcano, 2020.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Ignacio Molina is Senior Analyst at the Elcano Royal Institute and Lecturer at the Department of Politics and International Relations at the Universidad Autnoma de ...

Read More +

Miguel Otero-Iglesias is Senior Analyst at Elcano Royal Institute and Professor in International Political Economy at the School of Global and Public Affairs at IE ...

Read More +