-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted one of the core foundations of the concept of human development — a healthy and long life.

The COVID-19 pandemic has not only affected economic thinking on the path of GDP growth, but also on the path of human development. It has impacted one of the core foundations of the concept of human development i.e. a healthy and long life. The Human Development Index (HDI) of the UNDP, which seeks to convert the transitory gains of economic growth into permanent profit of human development, has shown its ephemeral nature in the face of COVID-19. The unprecedented calamity has brought to fore a chink in the armour of human development, which can wipe out gains made in enhancing choices and capabilities of humans — with a single stroke.

COVID-19 is not a one-off event. Just as nuclear weapons are a reality of the world, so will pandemics be in the days ahead. It is known for sure now that pandemics will continue to happen in the future and their intensity is only going to increase with time. With humanity brought to a standstill to curb the growth of the disease, a key question emerges on how to hedge the gains made in human development — over the years — without having to start from the beginning. A possible approach can be by developing a metric within HDI called ‘pandemic preparedness’, which will judge nations on three core assessments of public health capacity and governance to deal with such an event in future.

Human development is measured using three core indicators of life expectancy (at birth), knowledge (mean years of schooling) and standard of living (Gross National Income per capita). It is a critique of the ‘economic growth before people’ model of development. The current model of calculating human development has not been perfect because of a lack of emphasis on epidemic prevention mechanisms within public health, while measuring performances of nations.

Public health is defined as the science and art of preventing diseases, prolonging life and promoting health and efficiency, through organised community efforts for control of community infections, sanitation of the environment, etc. The HDI with its emphasis on life expectancy has till now focused on reducing the impact and occurrence of endemic diseases, without laying equal focus on epidemics. With a systematic rise in cases of public health emergencies dealing with epidemics over the years (SARS, MERS, H1N1, Avian influenza) culminating into the current crisis, measuring epidemic management capacities of nations to hedge the progress made in life expectancy, becomes important.

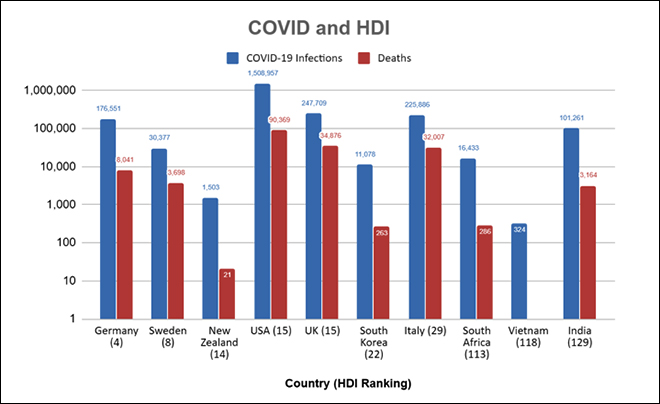

Figure 1

Source: Coronavirus Resource Center, John Hopkins University & Medicine | Note: HDI Rankings of 2019 are taken

Source: Coronavirus Resource Center, John Hopkins University & Medicine | Note: HDI Rankings of 2019 are takenIn the backdrop of the ongoing COVID-19 crisis, an analysis of the data in Figure 1 for infections and deaths in countries using their HDI rankings, brings out this shortcoming. It is observed that though countries like Germany, Sweden, USA, Italy and the UK rank very high on the HDI and have the highest life expectancies around the world, they are oddly the worst affected. As of 2 May 2020, these countries topped the charts of coronavirus deaths worldwide per million population. A brief analysis of this strange phenomenon shows that while healthcare facilities have been strengthened during normal times (hence high life expectancy), all the gains made are wiped out with a single case of pandemic.

However, there are a few outliers to this trend like South Korea and New Zealand. Both these nations have a high life expectancy of 83.50 years and 82.80 years respectively and are ranked very high on the HDI. The methods and approaches used by these countries in keeping low rates of infections and deaths are being hailed as a model for replication across the world. Another key highlight of the analysis is the exceptional performance of developing countries like Vietnam, India and South Africa. These middle ranking (HDI) countries with mediocre life expectancies (due to high incidences of endemic diseases) have managed to keep COVID-19 infections and death rates at some of the lowest levels in the world.

So what can be the possible conclusions for the offbeat trend witnessed during these times? One, success in managing endemic health emergencies during normal times need not be replicated in times of a pandemic. Second, low cases of diseases due to focus on improving the standard of living has its merits, however, it can have a flip side as well. Countries start to take their health systems for granted, and so do people. Third, withdrawal of state and excessive privatisation especially in the developed world in terms of providing essential services like food, shelter and health facilities can take a toll during pandemics. Finally, active intervention of the government can have a positive effect on managing health emergencies like a pandemic.

After analysing the impact of pandemics on the HDI, seen through the high mortality in countries having high life expectancies, the need for measuring epidemic management becomes imperative. A new indicator called ‘pandemic preparedness’ is the need of the hour. This new indicator has three core values of assessment which are as follows.

A government’s response to any emergency is of critical importance. A stable and coherent policy prepared in accordance with expert advice and using a scientific approach can have a tremendous impact in dealing with public health emergencies similar to COVID-19. The policy response indicator seeks to examine the time taken by the government of a country to come up with a coherent response to epidemic management. It seeks to also highlight the importance of such a policy at the early stages of a crisis such as COVID-19 through non-pharmaceutical measures, such as lockdowns and social distancing.

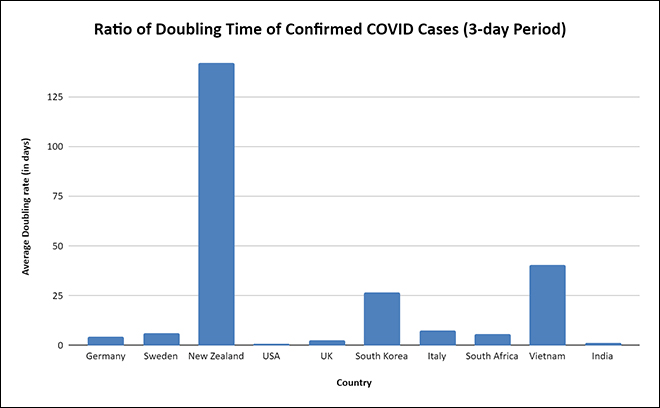

Figure 2

Source: Our World in Data

Source: Our World in DataThe above graph is curated using the doubling time of confirmed COVID-19 cases (three-day period). A five-day average using the days — when the cases reached 100 or above and two days before and after that day — of the doubling time was calculated. Then, again a similar average was calculated using the same method after exactly one month when 100 or above cases were reached. A time-lapse of one month was the period when governments of the chosen sample had instituted measures such as lockdowns and physical distancing. Finally, the ratio (plotted on the graph above) of average doubling time taken after employing strict measures to curb the spread of the virus to the average doubling time of the first few cases was calculated.

Ratio = Average doubling time after the precautions

Average doubling time for the first few cases

The higher the ratio, the better it is. It proves the efficacy of non-pharmaceutical interventions by governments, such as lockdowns and physical distancing. From Figure 2, the positive impact of effective government response has been proven in countries like South Korea, New Zealand and Vietnam which have been successful in not only managing the exponential growth of the disease in the first phase, but have stemmed the second wave of infections or avoided it altogether.

In addition, successes are also witnessed in other countries such as India and South Africa. These countries may not boast of robust health infrastructures; but they have stemmed the exponential growth and managed to help out countries in dire need through exports of critical pharmaceuticals, PPEs, etc. Thus, all these successes can be attributed to a pro-active and scientific governmental response that needs to be represented within HDI.

A critical factor that enables tackling pandemics is having a robust health infrastructure that can withstand the pressures, challenges and requirements in terms of prevention, cure and vaccines. COVID-19 has emerged as an unprecedented challenge for the medical fraternity in this regard.

In the current pandemic, nations which prided themselves on the state-of-the-art health infrastructure have been found lacking in terms of pharmaceuticals, testing capacities and critical medical equipment such as ventilators, PPEs and masks. The situation has been grim in nations like the US, Italy and France, to name a few. The low cases of endemic diseases due to an improved standard of living have created a health infrastructure which is deficient in dealing with pandemic emergencies of the scale of COVID-19.

The proposed indicator seeks to assess these critical deficiencies in the health infrastructure of nations so as to prepare them for any anticipated pandemic event. The core values which will be assessed would include — first, the current capacity of hospitals, community clinics, nursing homes, etc. to deal with a surge in cases (10,000 or more); second, analysing the shortcomings in the standard procedural response to a pandemic such as testing capacities, procurement and production of essential medical commodities such as PPEs, masks, gloves etc; finally and most importantly, ensuring that there is a minimum disruption of the established health infrastructure while dealing with unprecedented pandemic emergencies.

Pandemics disrupt several aspects of everyday lives including access to essential goods and services like food and medicines. As countries are forced to institute strict mechanisms to protect people, such abrupt measures impact the crucial lifelines of modern-day life — the supply chain. Mobilisation of resources becomes a vital task in such times. It is, therefore, necessary to understand what ‘mobilisation of resources’ means during a pandemic and why it is crucial to measure a country’s preparedness in terms of its ability to maintain a seamless system.

Mobilisation of resources during a pandemic means mitigating the impact from shock and tackling shortage of farm essentials, food shortages, shortage of essential medical equipment effectively through out-of-the-box solutions. For example, India, transformed its unused railway compartments and hotels into quarantine shelters to ensure that there is no shortage in the long-run. The concept is also crucial to measure because it reduces the dual burden and ensures that all resources are utilised to tackle the pandemic.

The proposed indicator will judge the extent to which certain essential supply chains of food and medical goods are immune to disruptions caused by such calamities. It will also measure the time taken by nations to rectify the disruptions caused to the supply chain and the novel methods employed to do so. Finally, the indicator would also determine to what extent a country is self-reliant in essential commodities such as food, medical goods and equipment, and health infrastructure.

The Human Development Index is an important index as it measures a country on its social and economic dimensions. However, the index introduced in 1990, needs to broaden its hemisphere by incorporating new variables. Coronavirus has thus given a wake-up call to rethink the HDI in terms of pandemic preparedness for the future.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Prachi Mittal was an Research Assistant with ORFs Centre for New Economic Diplomacy(CNED). Her research focuses on development economics Indian economy and the Sustainable Development ...

Read More +

Shreya Mishra is Masters in International Relations. She currently works as a Junior Research Fellow at Jindal School of International Affairs O.P. Jindal Global University. ...

Read More +