The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) grouping is geographically “India-centric”. This presents both opportunities and challenges for Delhi. Geographical realism and taking a leadership role drives Delhi’s pro-active regional diplomacy in combating COVID-19 that has been rapidly evolving into a regional crisis.

Locational centrality and asymmetry in size and capabilities allow India to shape the contours of cooperation in the SAARC region. At the same time, India’s location exposes it to challenges on all fronts, particularly when it is a threat that does not respect national boundaries.

In a region where borders are highly porous and there are several places with densely populated borderlands, the only effective way to combat challenges such as pandemic is through collective response. Given this ground reality, fighting the deadly virus requires a regional response to contain the spread of the infectious virus through land borders. This would have prompted Delhi to initiate its SAARC diplomacy in the wake of COVID-19 crisis.

Two SAARC member-states (Afghanistan and Pakistan) share long land borders with Iran, a country that has become a hotbed of the COVID-19 crisis. When Delhi initiated the regional approach to combat the coronavirus, the third highest number of coronavirus deaths was recorded in Iran after China and Italy.

To be sure, four SAARC member-states share land boundaries with China, the epicentre of COVID-19 outbreak. However, the number of coronavirus cases in Tibet Autonomous Region that shares land borders with the SAARC member-states was low with the sole COVID-19 patient reportedly recovered and discharged from hospital on 12 February.

Also, at the time of the announcement of Delhi’s regional initiative by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, there was no confirmed COVID-19 case in Myanmar, a country that shares long land border with India’s Northeast and a member of the BIMSTEC (Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multisectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation). Moreover, no confirmed coronavirus case was reported in India’s Northeast states until the first positive case was reported in Assam only on 21 March. This also partly explains Delhi’s decision to activate SAARC and not BIMSTEC for the regional initiative to counter COVID-19.

Apart from the geographical factor, another reason that seems to have prompted Delhi to undertake the initiative is its desire to take regional leadership role. In recent years, India has been positioning itself as “first-responder” in regional humanitarian crisis and taking leadership role in managing emergency situations under its “Neighbourhood First” policy.

In 2015, when a tragic earthquake of 7.9 magnitude struck neighbouring Nepal, India was the first to send relief teams and aid. India has also been the first responder in other crises that have struck Indian Ocean littorals and islands. In 2017, India was the first to respond to the devastating Cyclone More that hit Sri Lanka and Bangladesh.

Delhi’s regional initiative to fight COVID-19 crisis is part of its willingness and preparedness to take leadership role in its neighbourhood in managing the emerging humanitarian crisis. Taking a pro-active role in the neighbourhood also pre-empts other major powers from taking the lead and allows Delhi to be at take centre-stage in shaping regional dynamics.

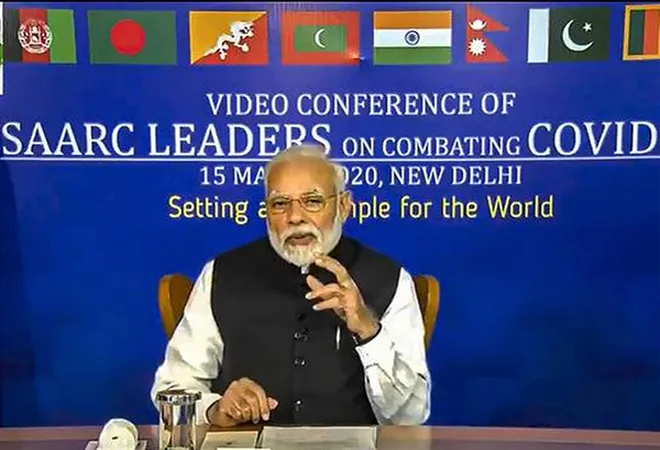

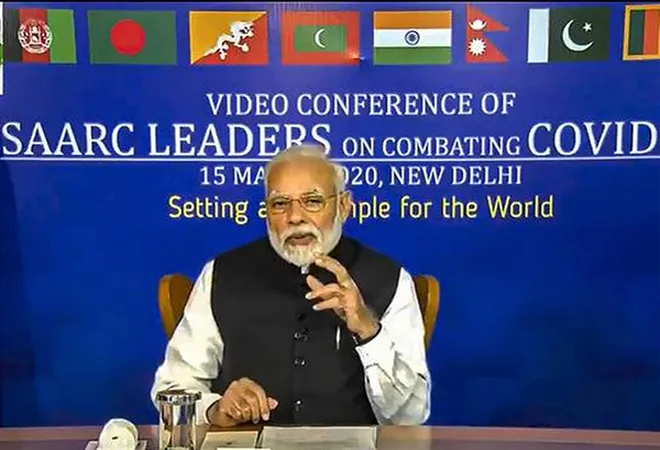

During the video conference with SAARC leaders, Prime Minister Modi announced the creation of the COVID-19 Emergency Fund with an initial contribution of $10 million. Delhi has asked SAARC countries to use the fund to meet the cost of immediate actions and medical requirements.

It appears that Delhi’s decision not to place the fund under the auspices of SAARC have been to keep the fund open and not confined to SAARC member-states as that would allow the fund to be used by other neighbours and partners outside the SAARC framework. India has reportedly assured support to Seychelles in countering the coronavirus is a case in point.

Delhi’s willingness to use SAARC existing mechanisms such as the SAARC Disaster Management Centre as well as proposing the need for SAARC to set up new mechanisms such as common research platform to coordinate research controlling epidemic within the SAARC region and to evolve common SAARC Pandemic Protocols indicate that it would not only use but also strengthen SAARC institutions to deepen cooperation in fighting common challenges such as a pandemic.

The positive response of SAARC member-states to India’s initiative with Bhutan, Nepal and the Maldives already making their contributions to the COVID-19 Emergency Fund demonstrate the commitment to collective fight against the pandemic. Much will however depend on the follow-up actions, particularly the various agencies executing and managing the regional initiative on the ground.

Delhi’s initiative has also raised hopes about SAARC’s rejuvenation. Although that prospect remains uncertain, the experience gained from working together in fighting COVID-19 may help create the habit of cooperation in the future. For now, one thing is clear. India’s call to collectively fight against coronavirus and the positive response it has received from SAARC member-states has helped the region prepare itself better in countering the pandemic that demands urgency and region-wide response.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV