-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

While national policies provide guidelines for achieving the net-zero targets, these seldom translate into effective strategies at the local level

Image Source: Getty

Cities will play a critical role in fulfilling India’s commitments to global targets related to sustainable, low-carbon, and resilient development. The 74th Constitution Amendment Act and multiple schemes initiated by the Central Government have supported city development. However, there could be a shortfall in achieving the targets because of existing policy and institutional frameworks that are not conducive to fostering the required changes. While national policies provide guidelines for achieving the targets, these seldom translate into effective strategies at the local level.

This mismatch between policy intent and implementation is the result of a gap in defining actions at the local level, inappropriate monitoring mechanisms at various levels of governance, and fragmented and incoherent institutional frameworks and governance mechanisms. For example, the transport department, on its own, cannot guide a sustainable mobility agenda and would need to consult with land development authorities in cases where land development plans are not coherent with the sustainable mobility agenda. This essay explores the required integration between different levels of governance to achieve the specified targets and the role of the Central Government in establishing such an integration framework.

The government is mobilising the adopted targets in coordination with states and union territories. India’s plans to reduce the intensity of emissions include increasing the share of renewable energy sources in power generation.

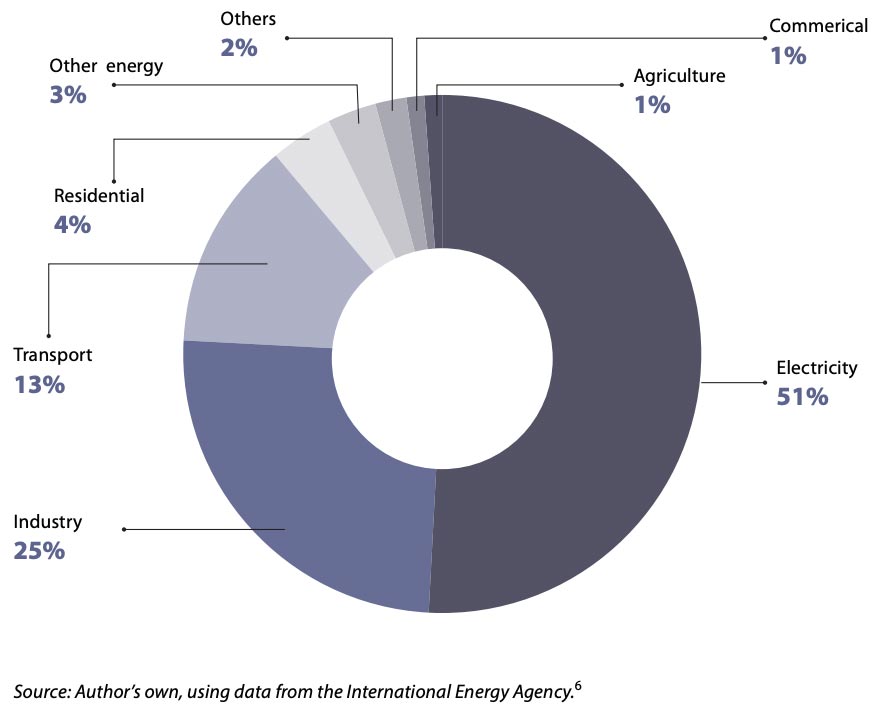

In 2022, India committed to reducing the emissions intensity of its gross domestic product (GDP) by 45 percent from the 2005 level by 2030. Subsequently, the Government of India (GoI) adopted a net-zero action plan with the horizon year of 2070, which provides strategies for the power, transport, building, and city infrastructure sectors. These include shifting the national grid to renewable energy sources, increasing the carbon sink, enhancing electric mobility, and generating green jobs. The government is mobilising the adopted targets in coordination with states and union territories. India’s plans to reduce the intensity of emissions include increasing the share of renewable energy sources in power generation. In 2021, the power sector contributed to 51 percent of India’s total carbon emissions (1.2Mt)—higher than the average global energy-related carbon emissions of 36.8 Gt.

Figure 1: Sectoral Contributions to CO2, India (2021)

Source: Author’s own, using data from the International Energy Agency.

Cities will play a critical role in achieving sectoral targets, particularly those of transport. While the transport sector contributed only 12.9 percent of the total emissions in 2021, this share has grown at a 4 percent annual average rate between 2011 and 2021. Promoting active mobility, such as walking and cycling, and encouraging the use of public transport, particularly buses, can help contain emissions in the Indian context. Emissions from India’s transport sector are currently low because of the high dependency on active modes and public transport systems. However, the infrastructure for active mode users is inadequate, exposing them to uncomfortable and unsafe conditions. The degrading air quality and increasing noise levels also expose users to more severe health impacts. Public transport users are exposed to similar conditions, as they travel by active modes to access or egress the system, which adds to the disutility of public transport.

In the existing scenario, the active modes are used by people who do not have alternatives. The existing conditions also push people towards personal motorised modes. Growing income levels will increase the affordability of motorised modes, travel activity, and travel intensity. The pandemic also influenced people to use more personal vehicles. Altered environmental conditions, such as degraded air quality and extreme weather events, also lead to people using more motorised transport modes. Altogether, existing infrastructure, growing incomes, and environmental degradation negatively impact the modal share of active and public transport in Indian cities.

This scenario highlights the urgency for India’s cities to adopt a retain-reduce-shift-improve approach to keep emissions from the transport sector under check. Such an approach would require enhancing the safety and comfort of active-mode users, reducing travel distances, which indirectly affect the choice of active modes, and providing an efficient bus transport system. Such improvements will enhance mobility for all, irrespective of income, age, gender, and physical health. It will also help achieve net-zero targets. Thus, the government must link net-zero transport actions with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the Indian context. The direct targets include Target 3.6 (Reducing road-related deaths), Target 9.1 (Modal share for all), and Target 11.2 (Access to public transport). The indirect benefits will include Target 5.2 (Ensuring women’s safety in public spheres—the percentage of women feeling safe at the roadside and in public transport); Target 7.3 (Improving energy intensity with a potential indicator of energy intensity per passenger km); and Target 11.6 (Air pollution, a potential indicator is emissions reduction per commuter).

It is imperative for India to retain existing active-mode users. Active modes, by addressing a significant travel demand, is witnessing a decline in its modal share. Therefore, India must encourage the use of public transport systems for long-distance trips to ensure reduced emissions per commuter. Better infrastructure for active modes will provide safe access to public transport systems, as the majority of public transport users walk to access the system.

Integrating bicycle infrastructure with public transport infrastructure can also provide better last-mile connectivity. Such measures would require an integrated planning mechanism with the appropriate disbursement of resources. Studies have shown that the 74th Constitutional Amendment Act has not been able to achieve its objective of providing cities with better financial and decision-making power because city legislature is dependent on state law and resource mobilisation is dependent on the economic base of the town.

The Government of India has also launched multiple schemes to support infrastructure development in cities, such as AMRUT and the Smart Cities Mission.

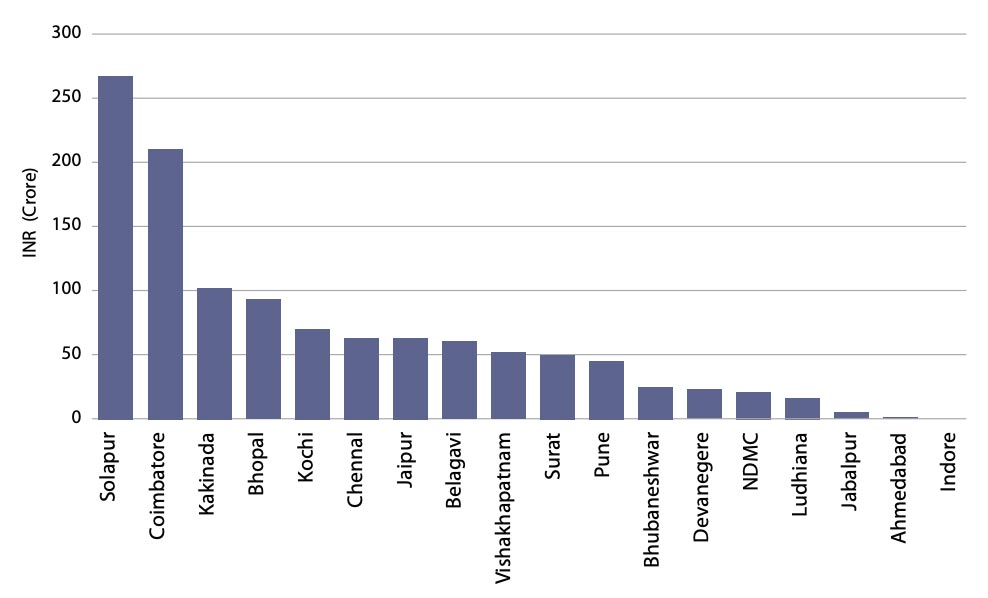

The National Urban Transport Policy (2006) provides a framework for improving transport infrastructure and meeting people’s mobility needs. However, the policy has not yielded significant changes in the way transport infrastructure is planned and provisioned. The Government of India has also launched multiple schemes to support infrastructure development in cities, such as AMRUT and the Smart Cities Mission. Support is available to states for the procurement of buses, provision of mass transit systems, and development of road infrastructure. Such schemes fund specific projects and require cities to submit proposals and detailed reports. However, the reports seldom discuss the need for the project, consider alternative approaches, or conduct impact assessments. Additionally, most states and cities consider transport projects in isolation—without integration with the city ethos, demography, and socioeconomic and cultural needs—and out of the purview of comprehensive city planning mechanisms. For example, the Comprehensive Mobility Plans for Kolkata, Chandigarh, and Pune suggest road expansion, building flyovers, and augmenting the bus fleet without considering the city size, needs, and demands, and conducting impact assessments of the proposed strategies and changing development patterns. These projects are primarily mass-transit-centric and based on the projected travel demand on road links, disregarding the need for improved active mobility. The Smart Cities Mission also pays cursory attention to improving active modes. This author’s analysis finds that few cities have been able to attract investments of more than INR 500 million for infrastructure provision for active modes, such as Coimbatore’s footpaths project and Bhopal’s bicycle sharing scheme, in the first round of the Smart Cities Mission.

Figure 2: Investment for Active Mobility Under Smart Cities Mission (First Round)

Source: Author’s own, using data on the first round of infrastructure investments for active mobility for the Smart Cities Mission.

India’s mandate towards achieving net-zero targets and the SDGs requires local actions and monitoring mechanisms. There are national-level net-zero targets as well as national-level and state level reporting mechanisms for the SDGs. However, the two do not percolate to city-level targets and strategies. The SDG vertical within NITI Aayog is entrusted with monitoring progress and localising SDGs at the state level, among other responsibilities. While states and districts report on SDG indicators, local actions are seldom designed according to the performance of urban mobility-related SDGs. Similarly, though there are national-level targets for achieving net-zero emissions by 2070, there is a lack of clarity on how much states and cities can contribute to this effort.

There is a need to integrate decision-making and reporting mechanisms between different levels of governance. Such integration would require defining targets at the city and state levels and a framework to measure and monitor progress. Decision-making must follow a top-down approach at the national level and a bottom-up approach at the state and city levels. National level targets must be distributed by sectors and at the state level. Impacts of potential pathways for achieving state-level targets within each sector can help define better strategies. The bottom up approach will need to consider cities’ infrastructure, demand, demography, and socioeconomic profiles.

The alternative scenario-based approach, as described in the revised Comprehensive Mobility Plan toolkit of 2014, can be adopted to understand the potential of strategies in reducing emission intensity while achieving just transitions. Some of the indicators identified in the toolkit, such as modal share, safety, and emission intensity, are directly linked to the SDGs. Such strategies and indicators can serve as the foundation for preparing an integrated plan at the city level and defining projects that need attention.

State and national governments can report on the number of cities with benchmark percentages of roads with footpaths. Similarly, an indicator of transport emission intensity per passenger can be measured at both city and national levels.

An integrated framework for assessing, reporting, and monitoring must adopt similar indicators at different governance levels. For example, states must consider an action indicator related to the percentage of roads with adequate footpaths to assess existing conditions and monitor progress at the city level. State and national governments can report on the number of cities with benchmark percentages of roads with footpaths. Similarly, an indicator of transport emission intensity per passenger can be measured at both city and national levels. At the national level, states must report periodic city-wise changes in transport emission.

Studies have shown that India may experience a shortfall in achieving net-zero emissions and SDG goals. The transport sector is not a major contributor to emissions in the current scenario, primarily because of a higher dependency on active and public transport modes. However, as the dependency on personal vehicles increases, emissions from the sector will grow. Integrating ‘net-zero’ with SDGs is needed to achieve “net-zero-just” development, which requires integrated decision-making processes as well as reporting and monitoring mechanisms at different levels of governance. Such a move would require a top-down approach at the national level to distribute targets by sector and state, whereas a bottom-up approach would be required at the city level in order to identify potential strategies to help achieve the targets.

A similar set of indicators is needed at the city, state, and national levels with regard to the reporting and monitoring framework. The indicators can be used to assess the status quo and define potential solutions based on the city’s needs and visions. National level policy frameworks should serve as a guide for cities, and city-level strategies need to be determined while considering a comprehensive planning approach.

Deepty Jain is an Assistant Professor at the Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi

This essay is part of a larger compendium “Policy and Institutional Imperatives for India’s Urban Renaissance”.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Deepty Jain is an Assistant Professor at the Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi ...

Read More +