On World Population Day, we direct our attention to the crucial field of contraceptive decision-making and its significant role in shaping sexual and reproductive health choices. While globally high maternal mortality rates highlight the pressing need for preventing unintended pregnancies and safeguarding maternal well-being, India grapples with its unique set of challenges in this regard. India’s

Maternal Mortality Rate (MMR) stands at 145 per 100,000 live births, resulting in a staggering 35,000 maternal deaths annually, constituting 12 percent of global maternal deaths. One important channel to prevent unwanted pregnancies and, in turn, maternal mortality is the use of

contraceptives.

Contraceptive usage is highly driven by the

power dynamics between women and men. With power dynamics typically tilted towards men, unmet needs become commonplace in cases where heterosexual couples disagree about family planning and its related outcomes. In such situations,

contraceptives may help women avoid unwanted and unplanned pregnancies. However, in

practice, about 63 percent of women in India do not use contraceptives, and among those who use them, about 32 percent report using modern contraceptives such as pills, intrauterine devices (IUD), injections, vaginal methods, condoms, female sterilisation, and male sterilisation, among others. Among women who report using modern contraceptives, 73 percent of women end up undergoing sterilisation relative to only 0.79 percent of men. Unsurprisingly the burden of sterilisation rests heavily on women with India leading in the prevalence of female sterilisation in

Asia. Together, these figures point out the importance of contraceptive usage, and in particular, women’s decision-making about contraceptive usage. In this article, the data from

National Family Health Survey-5 (NFHS-5) helps us delve into the socio-demographic factors influencing women’s contraceptive decision-making, with a particular focus on their choice to use contraceptives solely.

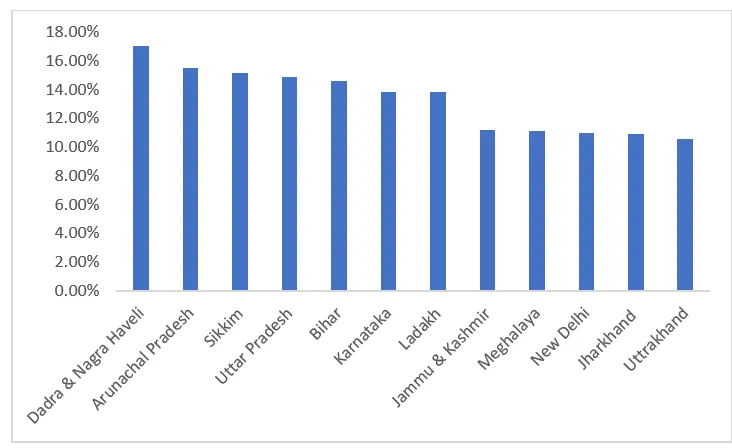

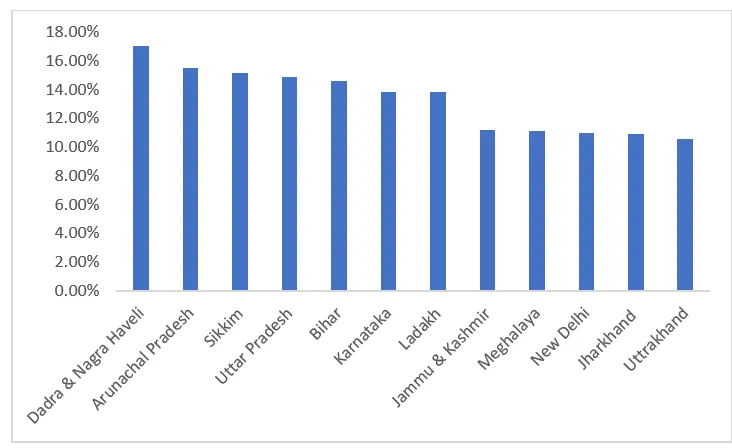

Figure 1. Top 10 states with highest women’s contraceptive decision-making rate.

Graph: Authors’ calculations using NFHS - 5 (2019-21) for India

Graph: Authors’ calculations using NFHS - 5 (2019-21) for India

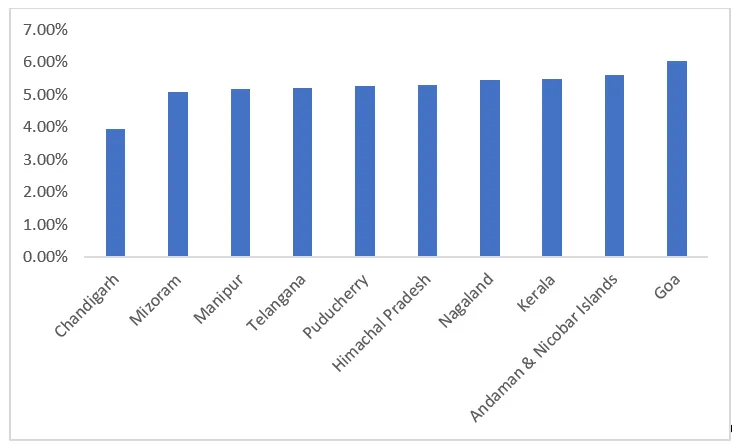

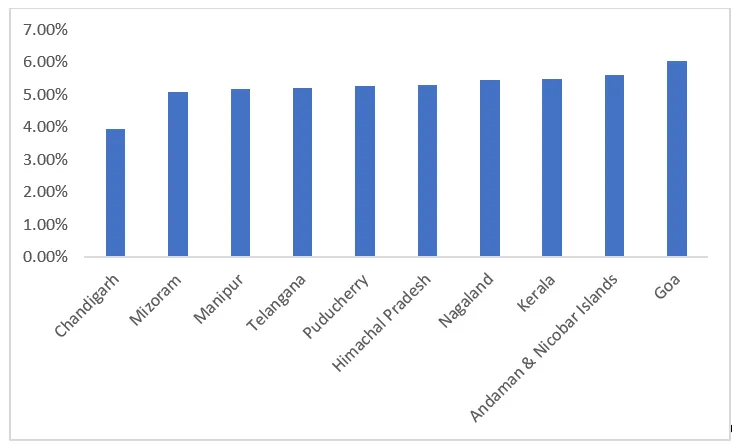

Around 10 percent of women in India take contraceptive decisions alone. These numbers remain similar in rural (10.14 percent), and urban (9.47 percent) areas. Figures 1 and 2 show the top-performing and bottom 10 states and union territories (UT) in contraceptive decision-making across India. The top-performing states and UT are Dadra & Nagar Haveli, Arunachal Pradesh, and Sikkim,

where 15–17 percent of women decide to use contraceptives themselves. Chandigarh scores the lowest in women’s contraceptive decision-making, which also corroborates with the high fertility rate in the UT.

Figure 2. Bottom 10 states with lowest women’s contraceptive decision-making rate.

Graph: Authors’ calculations using NFHS - 5 (2019-21) for India

Graph: Authors’ calculations using NFHS - 5 (2019-21) for India

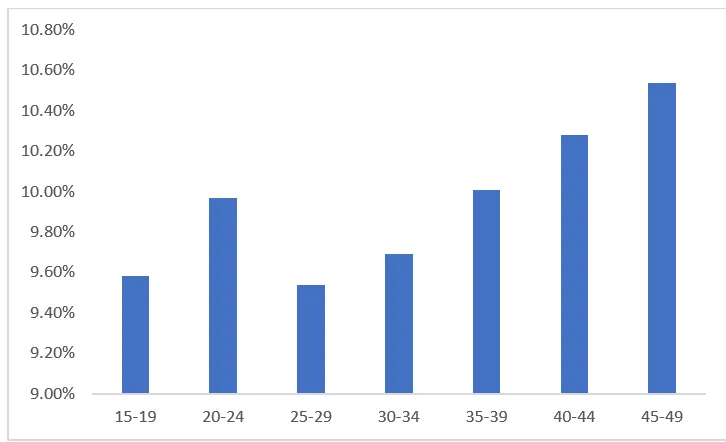

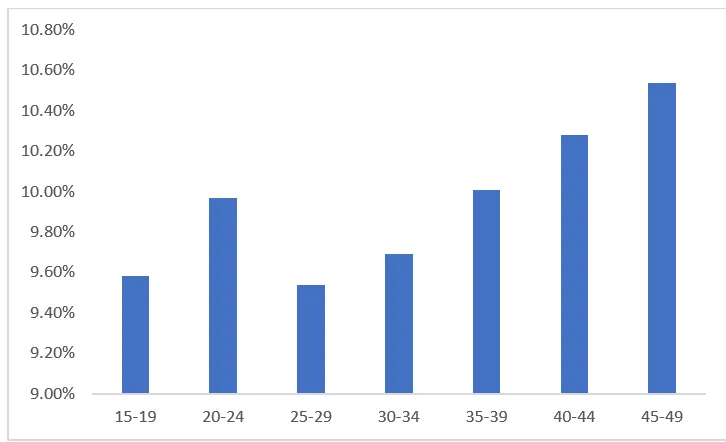

If we look at contraceptive decision-making across age groups, as shown in Figure 3, the scenario reveals abysmally poor statistics across all ages. We note marginally higher sole contraceptive decision-making for women in the age group 20-24, which further reduces for the age group 25-29 years. We see a modest increase in the figures with age perhaps indicating that older women gain more autonomy with time and thus, have a greater say in the use of contraceptive decisions.

Figure 3. Percentage of women making contraceptive decisions across age groups.

Graph: Authors’ calculations using NFHS - 5 (2019-21) for India

Graph: Authors’ calculations using NFHS - 5 (2019-21) for India

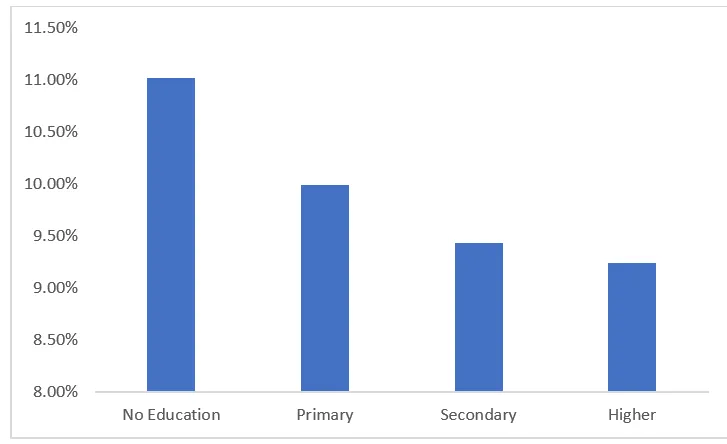

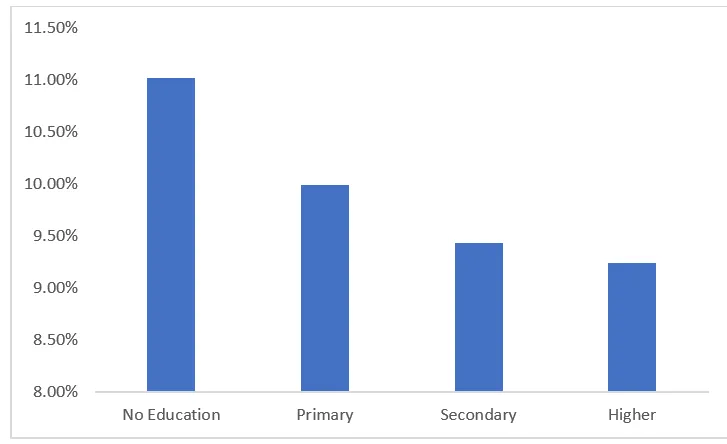

One could argue that attaining higher education does not translate into women having decision-making power in the household, which also restricts their ability to make sole contraceptive decisions.

Next, we try to understand the role of formal education in women’s contraceptive decision-making. Figure 4 indicates that sole decisions about the use of contraceptives actually decline with more education. A woman's education does not seem to strengthen her position about that of her partner in reproductive practices. One could argue that attaining higher education does not translate into women having decision-making power in the household, which also restricts their ability to make sole contraceptive decisions. Additionally, relative education about the husband may also matter in contraceptive decision-making.

Figure 4. Percentage of women making contraceptive decisions by education levels.

Graph: Authors’ calculations using NFHS - 5 (2019-21) for India

Graph: Authors’ calculations using NFHS - 5 (2019-21) for India

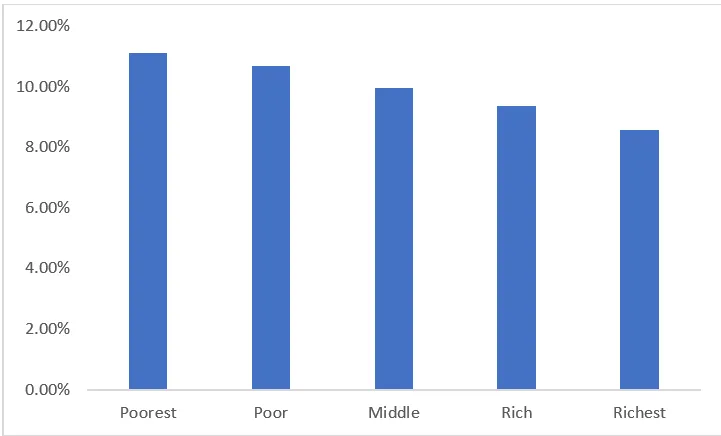

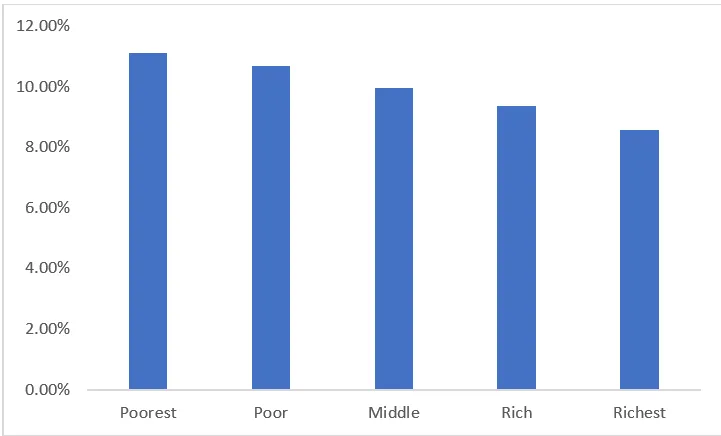

Considering the unexpected effect of education, we examine the effect of household wealth. Similar to the correlations with levels of education, contraceptive decision-making declines with a higher wealth index of the households. Figure 5 further highlights the inverse relationship between wealth and women’s reproductive practices, with the lowest levels of sole decision-making power in the richest households.

Figure 5. Percentage of women making contraceptive decisions across wealth index.

Graph: Authors’ calculations using NFHS - 5 (2019-21) for India

Graph: Authors’ calculations using NFHS - 5 (2019-21) for India

Community-level indicators of autonomy and general awareness about fertility practices appear to be important predictors of women’s contraceptive decision-making.

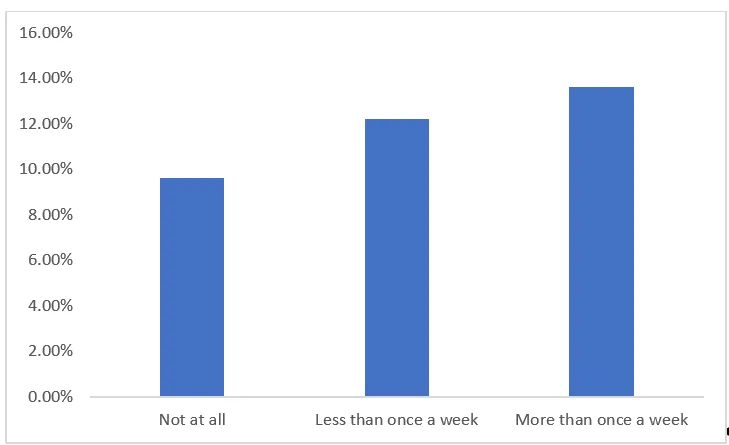

The Government of India, in the past, has run multiple programmes via radio such as include

Radio Chat Show, “HUM DO”, and other

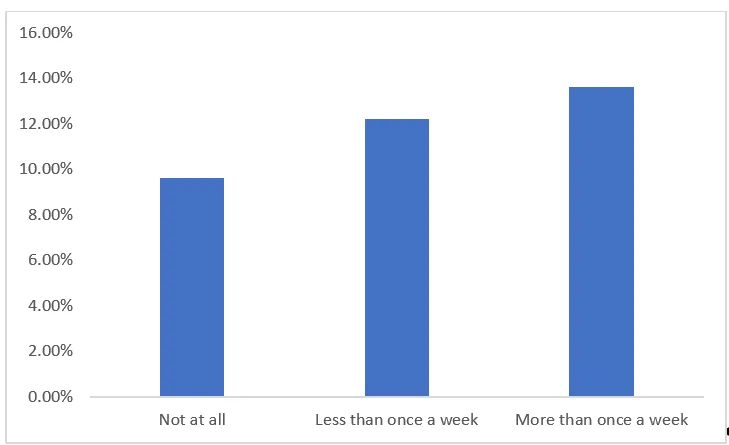

family planning campaigns to increase awareness about contraceptive practices. Given this, we look at the variation in contraceptive decision-making among the women who listen to the radio versus those who do not. Our results show that women who listen to the radio at least once a week, have higher contraceptive decision-making power, as compared to those who do not listen to it at all, indicating that general awareness perhaps encourages women to take decisions about using contraceptives themselves. This finding coupled with the observation that contraceptive decision-making declines with women’s education is in line with the

evidence that the educational level of other women in the neighbouring areas tends to affect a woman's contraceptive use above and beyond that of her education. Community-level indicators of autonomy and general awareness about fertility practices appear to be important predictors of women’s contraceptive decision-making.

Figure 6. Percentage of women making contraceptive decisions by radio.

Graph: Authors’ calculations using NFHS - 5 (2019-21) for India

Graph: Authors’ calculations using NFHS - 5 (2019-21) for India

Together, these statistics are suggestive of patriarchy, manifested by unequal power relationships in a union, playing a major role in women’s contraceptive decision-making. In other words, patriarchy is driven by taboos and myths perhaps stopping women from gaining autonomy to independently take such decisions solely. Our findings call for immediate attention to the inclusion of men along with women in family planning initiatives.

On the whole, we find disconcerting trends in women’s sole contraceptive decision-making power. It remains low in urban and rural areas and across all age groups. Their educational attainment or household wealth does not seem to positively influence their autonomy in such decisions. We note a rise in their decisions regarding fertility practices only among the women who listen to the radio every day. As such, her higher autonomy in contraceptive decisions could be the impact of the various family planning messages run by the government. The government ought to include sessions around contraceptive usage as a part of programmes (Kanyashree, Ladli Scheme, etc.) that focus on empowering women and these programmes may further be promoted via various other mass-media channels such as television and newspaper which have a large network base and the potential to reach a larger audience. Increased awareness will likely reduce the taboos and cultural sensitivities around the issue and will provide women more autonomy to decide whether or not to use contraceptives.

Karan Babbar is Assistant Professor at the Jindal Global Business School, OP Jindal Global University.

Manini Ojha is an Associate Professor at the Jindal School of Government and Public Policy, O.P. Jindal Global University.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

On World Population Day, we direct our attention to the crucial field of contraceptive decision-making and its significant role in shaping sexual and reproductive health choices. While globally high maternal mortality rates highlight the pressing need for preventing unintended pregnancies and safeguarding maternal well-being, India grapples with its unique set of challenges in this regard. India’s

On World Population Day, we direct our attention to the crucial field of contraceptive decision-making and its significant role in shaping sexual and reproductive health choices. While globally high maternal mortality rates highlight the pressing need for preventing unintended pregnancies and safeguarding maternal well-being, India grapples with its unique set of challenges in this regard. India’s

PREV

PREV