-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The mounting toll of Himalayan disasters underscores the urgent need to reimagine development, shifting from extractivism and unchecked infrastructure growth to ecological stewardship and resilience.

The ongoing trail of disasters in the Himalayas, including in Uttarkashi, Kishtwar, and various parts of Himachal Pradesh, is neither an aberration nor isolated acts of nature. They reflect a larger systemic failure in treating the Himalayas as an inexhaustible resource base and a tourist frontier rather than an environmentally sensitive ecosystem.

The Himalayas, also known as the Third Pole, are young fold mountains that continue to grow at a rate of 10 mm per year, with the Indian subcontinent subsiding northwards at a rate of 5 cm per year. As one of the most seismically active areas in the world, the region is prone to earthquakes, slope failures, landslides, and mass movements. These render the environmental baseline of the Himalayas naturally unstable, even before factoring in the anthropogenic imprint. Over the past decades, the Himalayas have witnessed massive urbanisation and development, often at the cost of the environment. The sobering number of disasters in the Himalayan states and the subsequent loss of lives and resources is unprecedented. Over the past three years, the Himalayas have witnessed some form of extreme weather event every seven out of ten days.

The political economy of Himalayan development must urgently reconcile extractivist, revenue-driven growth strategies with the need for environmental and ecological stewardship.

Increasingly catastrophic events, such as the Uttarakashi flash floods or the Kedarnath Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOF), necessitate an urgent, paradigmatic shift in how India and its Himalayan states approach this eco-sensitive region. The political economy of Himalayan development must urgently reconcile extractivist, revenue-driven growth strategies with the need for environmental and ecological stewardship.

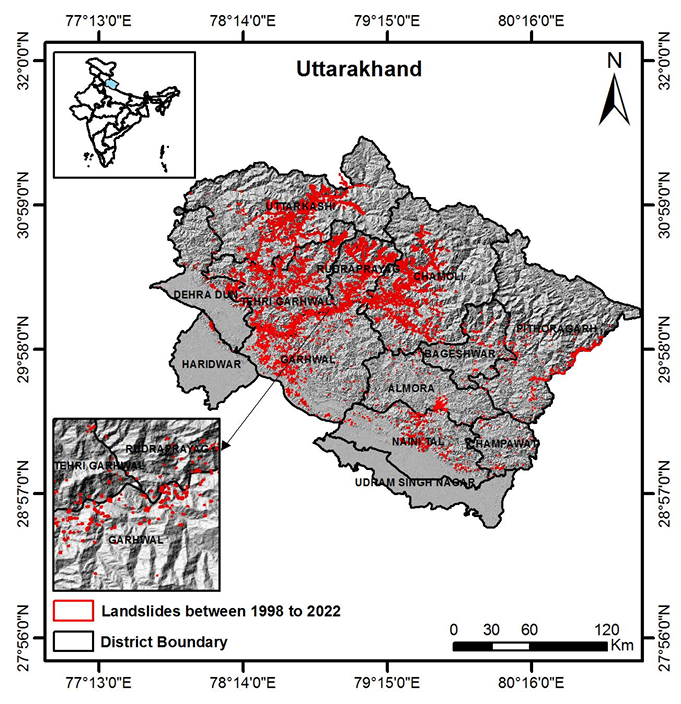

The Indian Himalayan Region comprises 13 states, including Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Himachal Pradesh, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim, Tripura, Uttarakhand, and West Bengal, as well as the Union Territories (UTs) of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh. Over the past three years (January 2022-March 2025), these states experienced extreme weather events on 822 of 1,186 days, resulting in the deaths of 2,863 people. Globally, landslides are the third deadliest natural hazard, with Colombia, Tajikistan, India, and Nepal among the countries facing the highest risk. The slope instabilities caused by mega infrastructure projects have made the Himalayas particularly vulnerable. The Landslide Atlas of India highlighted that between 1988 and 2022, Mizoram witnessed the highest number of landslides at 12,385, followed by Uttarakhand at 11,219, and Tripura at 8,070. Figure 1 shows landslide occurrences in Uttarakhand between 1988 and 2022. Landslide exposure analysis indicates that Rudraprayag and Tehri Garhwal are the most landslide-prone districts in the country.

The Landslide Atlas of India highlighted that between 1988 and 2022, Mizoram witnessed the highest number of landslides at 12,385, followed by Uttarakhand at 11,219, and Tripura at 8,070.

Figure 1: Map depicting the landslides in Uttarakhand, India, that occurred between 1998 and 2022.

Source: Landslide Atlas of India.

The region’s location in a high-seismic zone further contributes to its hazard profile. It also houses the Tehri Dam, India’s highest, which was arguably built on an active fault line, raising concerns about the potential for compounding disaster vulnerability. In 2021, a massive rock and ice avalanche in the upper catchment of the Rishiganga river in Chamoli, Uttarakhand, caused widespread devastation, killing more than 200 people and damaging two hydropower projects. The floods washed away the 13.2 MW Rishiganga hydropower project and damaged the under-construction 520 MW NTPC hydropower project at Tapovan on the Dhauliganga river.

With climate change exacerbating the melting of glaciers, the Himalayas are at a higher risk of GLOF. Studies have indicated that glacier melt in the Himalayas has created more than 5,000 glacier lakes that are naturally dammed by potentially unstable moraines. The collapse of these dams would cause catastrophic GLOFs, as witnessed in Kedarnath in 2013 with the bursting of Chorabari Tal lake. In 2023, the South Lhonak GLOF in Sikkim released 50 million cubic metres of water, leading to a multi-hazard cascade and causing transboundary impacts along the Teesta river, hundreds of kilometres downstream, in Bangladesh. Mapping 3,624 glacial lakes in the Koshi, Gandaki, and Karnali river basins of Nepal, China, and India revealed that 47 of the 1,410 lakes with an area of 0.02 square kilometres or larger are critically hazardous. This could cause GLOFs in Nepal, China, and India. Warming temperatures that allow moisture-laden air to condense rapidly over elevations lead to frequent cloudbursts and flash floods, indicating an increased climate vulnerability of the Himalayas. The Uttarkashi flash floods produced torrents that obliterated settlements and commercial establishments within moments, bringing into question the violations caused by human activity in the Bhagirathi Eco-Sensitive Zone (BESZ) and the ecological impacts of the Char Dham highway project.

With climate change exacerbating the melting of glaciers, the Himalayas are at a higher risk of GLOF. Studies have indicated that glacier melt in the Himalayas has created more than 5,000 glacier lakes that are naturally dammed by potentially unstable moraines.

Deconstructing the Development Dilemma

The Himalayan ecological crisis is emblematic of a political economy of resource dependency and extractivism, where the mountains are metamorphosed into the circuits of capital. The central and state governments have increasingly treated them as peripheral resource repositories, harnessed for the core’s capital accumulation through hydropower, timber, water, and tourism. The Himalayan Region has enormous hydropower potential with an estimated installed capacity of 46,850 MW and the potential to generate an additional 115,550 MW of power. Already, the governments have planned several large hydropower projects to harness this potential, largely overlooking the significant ecological, social, and geological consequences. In addition to geological and tectonic instabilities, the conversion of agricultural lands and forests to roads, tunnels, and buildings has caused significant land-use changes, leading to water scarcity due to the drying of natural water flows and springs. Communities living around hydropower project areas are the most vulnerable to land acquisition, displacement, and livelihood disruption.

The unregulated growth of tourism has led to the proliferation of tourist infrastructure, such as hotels, homestays, tourist vehicles, and parking lots, often resulting in encroachment on ecologically sensitive areas. The total number of tourist arrivals in the state of Himachal Pradesh in 2024 alone was 18,124,694. The seasonal surge in tourist influx further strains the delivery of basic services and challenges waste management in the mountains. The increase in water consumption patterns associated with tourism has also led to a water crisis in many mountain cities. Traffic congestion has cascading ecological impacts, with increased vehicular emissions degrading air quality and contributing to early snowmelt.

The Himalayan ecological crisis is emblematic of a political economy of resource dependency and extractivism, where the mountains are metamorphosed into the circuits of capital.

In Himachal Pradesh, the Supreme Court of India recently attributed anthropogenic activities, including hydroelectric power projects, four-lane roads, deforestation, and the proliferation of multi-storey buildings, to ecological destruction and an increasing disaster risk. Unscientific cutting or blasting of hill slopes for infrastructure projects is destabilising the slopes, altering local hydrology, and making the slopes vulnerable to landslides and flash floods. The apex court warned that revenue “cannot be earned at the cost of the environment and ecology.”

Development projects in the mountains are often justified under the rhetoric of strategic requirements and national development. However, the distribution of benefits is usually asymmetric, with the local communities bearing a disproportionate risk of ecological and livelihood disruptions, as well as disaster vulnerabilities. The Himalayan region is currently at the convergence of climate extremes, geomorphic fragility, and a high anthropogenic footprint. It risks being locked in a vicious cycle if development planning is not reoriented to account for ecological thresholds. This requires deeper introspection of whether environmental degradation is an inadvertent byproduct of the current growth model or an embedded feature that externalises ecological costs.

The Himalayan region is currently at the convergence of climate extremes, geomorphic fragility, and a high anthropogenic footprint. It risks being locked in a vicious cycle if development planning is not reoriented to account for ecological thresholds.

Development in the Himalayas must, therefore, be reimagined from the ground up, taking into account environmental concerns, ecological awareness, and community resilience. Hazards mapping and demarcation of high-risk zones must be at the core of land-use planning to prevent construction in vulnerable areas. Indigenous knowledge systems, along with community-focused participatory planning, must inform disaster preparedness, early warning systems and monitoring. Technological innovations for low-impact and climate-resilient infrastructure must be considered in conjunction with tourism policies that regulate tourist footfall, calibrated to the region’s carrying capacity. An integrated, equity- and justice-oriented framework specifically curated to the needs and challenges of the Himalayas can help secure a resilient future.

Soma Sarkar is an Associate Fellow with the Urban Studies Programme at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Soma Sarkar is an Associate Fellow with ORF’s Urban Studies Programme. Her research interests span the intersections of environment and development, urban studies, water governance, Water, ...

Read More +