-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The dynamic nature of digital spaces urgently requires existing scholarship to be regularly updated. This has most certainly been lacking, particularly following Twitter’s transformation to X in 2022.

Image Source: Getty

For better or worse, the ubiquitousness of digital media continues to greatly influence public perception. Most mainstream and alternative news networks, journalists, and political leaders have already established their presence on social media platforms. Increasingly, people now rely on giant social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and X (formerly known as Twitter) as their primary source of news and information.

In an environmental context, platforms like X have become key instruments in facilitating climate awareness and activism by enabling credible sources to share and amplify facts and new developments. This has also created a free space for discussion on issues of climate action and policy. Policymakers can benefit from gauging public opinion via social media.

Conversely, the predominance of digital media has also resulted in a marked increase in divisive narratives about climate change. A 2022 study on polarisation in online environmental discourse investigated this intersection of political polarisation and climate change, using X data from 2014 to 2021 to study the United Nations Conference of the Parties on Climate Change (COP). It revealed a significant increase in polarisation during COP26, following relatively low levels in the previous five years. The study also demonstrated how this increase is driven by increasing right-wing activity, a fourfold increase since COP21 when compared to pro-climate groups.

A 2022 study on polarisation in online environmental discourse investigated this intersection of political polarisation and climate change, using X data from 2014 to 2021 to study the United Nations Conference of the Parties on Climate Change (COP).

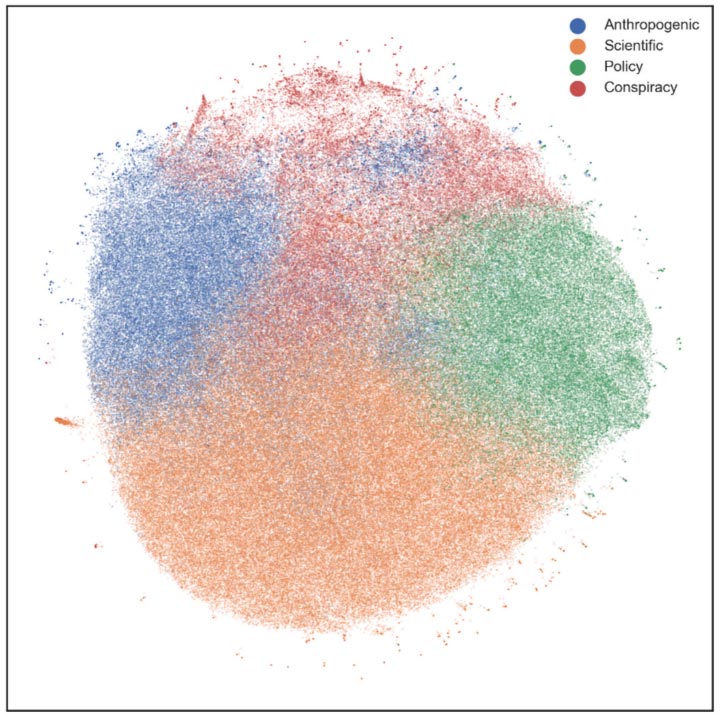

Another study was conducted by the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) in Vienna which used a selected sample of 333,635 English tweets focused on man-made climate change. It analysed the patterns that emerged from their content and the kinds of sources they referenced.

The study used Natural Language Processing (NLP) and machine learning for analysis to categorise the data into four main clusters based on the prevailing narratives and sources referenced:

Visualisation of tweets in the dataset across clusters, IIASA 2022

While social media platforms have a built-in risk of polarising public opinion, it has also been an important catalyst for climate action. Widespread use of these platforms has allowed for movements like #FridaysForFuture and Extinction Rebellion to grow rapidly through their online presence.

Masked protestors at a climate demonstration by Extinction Rebellion held in Berlin (Getty Images)

Climate activists in India have also used social media platforms to organise demonstrations as the climate strike movement continues to gain momentum globally.

Nevertheless, netizens in India are quite different to those in the West. India, importantly, has a massive user base, with greater dependence on digital media and particularly visual content. This leaves a sizable user base even more vulnerable to disinformation, as doctored videos and images have become commonplace. The majority of previous studies have been based on textual content, often further restricted to posts in the English language. New scholarship on the subject must include multimedia and visual content as a crucial component, as well as the importance of non-English languages.

Digital spaces have been invaluable facilitators, making these sources accessible and comprehensible to a massive global audience.

As is the case with most of the Global South, India is on the front lines of the battle against climate change. News coverage of climate events in India is typically more rigorous, even on digital media. The use of visual content and multimedia has been effectively used to report on and explain these issues, particularly the human cost and devastating environmental impact being felt by residents of these affected areas. Reports on the landslides in Himachal Pradesh and the severe heat waves in New Delhi are among the many examples of this. Digital spaces have been invaluable facilitators, making these sources accessible and comprehensible to a massive global audience.

The recurring presence of polarisation, algorithmic feedback silos, and artificial online traffic manipulation are some of the most dangerous byproducts of social media’s omnipresence. It has, therefore, become a double-edged sword; social media is both a phenomenal opportunity to address climate change, as well as one of the most demanding challenges.

India and the Global South have an important opportunity to analyse and effectively use social media as a conduit for constructive climate discussion, to continue raising public awareness on pressing ecological issues like North-South disparities and the severity of climate change.

One of the most challenging tasks is measuring and tackling disinformation on social media on the climate crisis. India is well-positioned to learn from the missteps in the Global North when addressing this problem. For instance, the Green Deal approved by the European Union in 2020 was particularly observed to be a major target of disinformation on social media. Many accounts falsely claimed that the EU’s Green Deal would enforce a ban on vehicles older than 15 years and mandate ‘carbon passports’. This led to growing discontent on social media; many Twitter users in Sweden at the time even argued for an exit from the EU in response. The impact of perception and awareness on climate action must not be underestimated.

It is important to recognise the role of the giant corporations operating social media platforms today. Digital media platforms have proven to be inherently dynamic spaces, bound to the volatility of multinational corporate ownership. This has widespread implications, affecting millions of users globally. Twitter’s transformation into X, for instance, has significantly altered the functioning and public perception of the platform. X’s revised policies have resulted in increased polarisation on climate issues. Several accounts that were banned for spreading misinformation and disinformation have since been reinstated. The increase in climate scepticism is one of the many effects these changes have had.

Since 2022, users have migrated to platforms like Meta’s Threads, Instagram or Mastodon, the open-source alternative instead. A 2023 study demonstrated the impact this has had on climate discourse on X, with nearly half of ‘environmentally oriented users’ (47.5 percent of accounts sampled) having become inactive on the platform following Musk’s takeover in 2022.

X’s revised policies have resulted in increased polarisation on climate issues. Several accounts that were banned for spreading misinformation and disinformation have since been reinstated.

X’s policies and Terms of Service (ToS) are in a perpetual balancing act with disparate domestic laws across the many nations it operates in. Most recently, X was banned entirely in Brazil following a failure to comply with legal orders from the government. Brazilian courts initially ordered the banning of six accounts for spreading fake news and misinformation. Musk has argued that doing so would go against X’s ToS regarding free speech. Eventually, in September 2023, Brazil’s Supreme Court enforced a nationwide ban on the platform.

Furthermore, new restrictions which placed X’s application programming interface (API) behind a hefty paywall have resulted in new challenges for research on the platform. This has made studies like those referenced prior to 2022 unfeasible, leaving a large void for research on the impact of social media.

While the significance of a giant like X cannot be ignored, this shift towards other platforms is a development that warrants serious attention. Social Media platforms that are more widely used particularly in India, such as Meta’s WhatsApp and Facebook must be of utmost importance for increasing climate education and tackling disinformation. This, in turn, also impacts policy regarding climate matters by providing a platform for transparency and discussion on a global scale.

There is a need to further study the impact of social media in India, with more comprehensive research in localised contexts. The dynamic nature of digital spaces urgently requires existing scholarship to be regularly updated. This has most certainly been lacking, particularly following Twitter’s transformation to X in 2022. This can prove to be an invaluable asset to policymakers and climate activists alike, to advocate for more scientific approaches to climate change. This is of even more importance in the Global South, where citizens disproportionately experience the severe consequences of the climate crisis.

Krishna Vohra is a Research Assistant with the Centre for Economy and Growth at the Observer Research Foundation

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Krishna Vohra is a Junior Fellow at the Centre for Economy and Growth. His primary research areas include energy, technology, and the geopolitics of climate ...

Read More +