Data centres are the linchpin of a nation's technological progress, serving as the nerve centers that power the information age. The need for robust and reliable data centre infrastructure cuts across the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), serving as an essential foundation for e-government, innovation and entrepreneurship, decent work, and economic growth. It comes as no surprise then that data sovereignty has gained traction over the past decade, particularly in the Global South. However, climate change threatens the very infrastructure that underpins the digital future, and its impact on data centres is a multifaceted challenge, with rising temperatures, extreme weather events, and changing environmental conditions posing significant threats to their reliability and sustainability, even as developing countries begin rolling out ambitious strategies and incentives to attract data centres.

The clouds that don’t bring rain

Walking through a data centre the size of an apartment complex in India’s largest data centre hub, two things stood out: First, our global information flows, even the ephemeral “cloud”, rely on physical infrastructure that stores, processes and moves data. Second, these rows upon rows of servers run hot.

Keeping data centres cool guzzles up water and energy, which in turn places stress on regions that will become increasingly drought-prone and water-scarce as climate change intensifies.

The ideal operating temperature range for data centres, according to the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) is 65°F to 80°F (18°C to 27°C approx.). Data centres also need to be climate controlled around other factors like relative humidity. It follows then that data centres guzzle up massive amounts of energy and water. A 2020 article remarks on the rapid growth in data centre workloads: in the span of just eight years (2010-18), data centrw IP traffic had grown tenfold, accounting for 1 percent of global electricity consumption—more than the total electricity consumption of Thailand. Although energy intensity improved in that period, this growth accounted for a 25 percent spike in global energy use. Furthermore, keeping data centres cool guzzles up water and energy, which in turn places stress on regions that will become increasingly drought-prone and water-scarce as climate change intensifies. Now, it appears that even with better energy efficiency, there just is not enough power to whet the world’s appetite for data centre capacity. CBRE’s Global Data Center Trends 2023 report notes record-low vacancy rates in data centres, driven by the rapid growth in AI, streaming, self-driving cars, and other new and emerging technology applications.

Currently, North America accounts for the majority of the world’s data centre capacity,[1] but projections indicate that the Asia Pacific data centre market is expected to grow 12.2 percent between 2020-24, with Southeast Asia alone growing at 12.9 percent. This is followed by Europe, the Middle East and Africa (EMEA) at 11.1 percent and North America at 6.4 percent.

Data sovereignty regulations are spurring some of the growth in data centre demand in the Asia Pacific region, especially outside established data hubs like Singapore and Tokyo.

Data sovereignty built in copper

Data sovereignty regulations are spurring some of the growth in data centre demand in the Asia Pacific region, especially outside established data hubs like Singapore and Tokyo. This includes data localisation mandates—some sectoral (Reserve Bank of India’s circular DPSS.CO.OD.No 2785/06.08.005/2017-18) and some pertaining specific sub-categories of sensitive data (such as telecom service provider data under Vietnam’s Cybersecurity Law).

National data centre policies focus on a few common pillars: the robustness and reliability of e-government services; security and trust in government collection of data; and building capacity and shared resources to bolster innovation and spur economic growth. Many developing countries have implemented or are deliberating data centre plans, either as standalone policies or as part of the larger incentive packages for digital infrastructure.

While some strategies mention the need for a steady supply of electricity and water for data centres, with proposals to offer competitive subsidies, few delve into strategies to combat potential resource stress, and how rapid climate change will impact the operating environment.

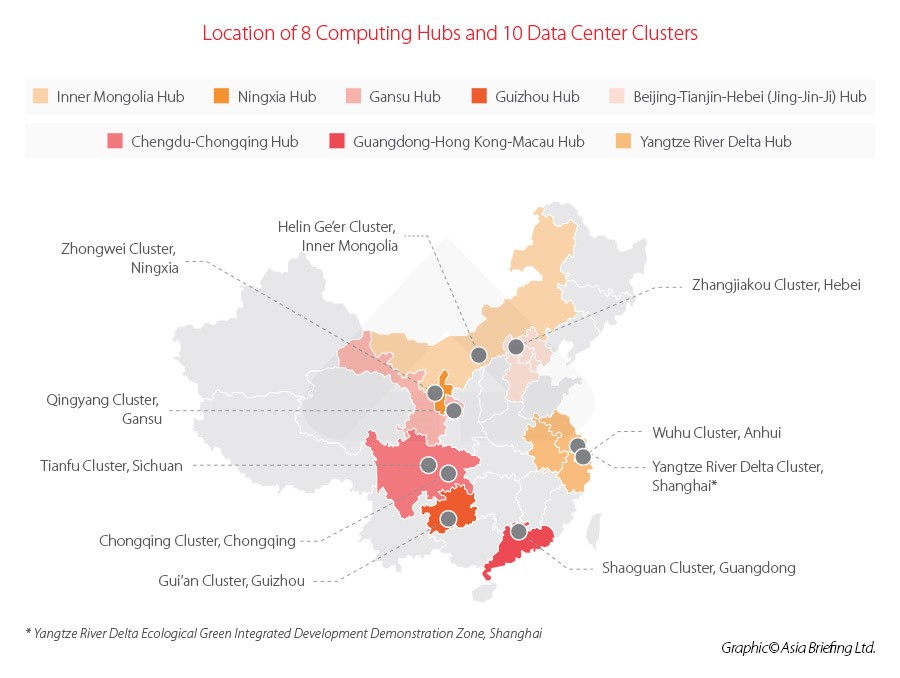

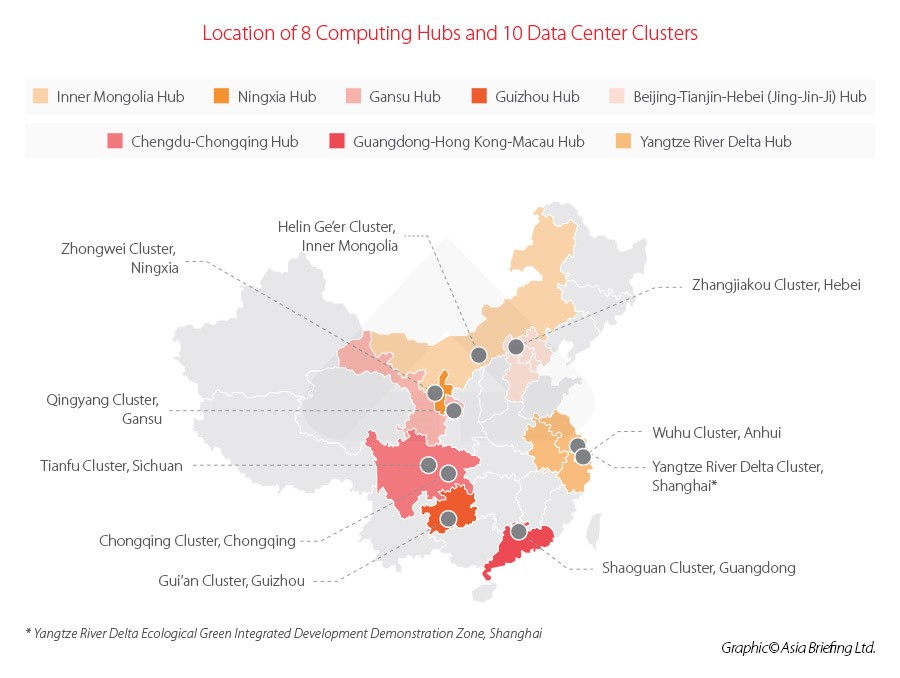

Figure 1: Current and proposed data center clusters in China.

Source: China Briefing

2023 was the hottest year on record, marked by a series of extreme weather events that have left their imprint on the global economy. Flooding in China led to a 2-5 percent drop in the country’s grain production. Meanwhile, South America had one of its worst droughts on record, with Montevideo, the capital of Uruguay, running out of potable water.

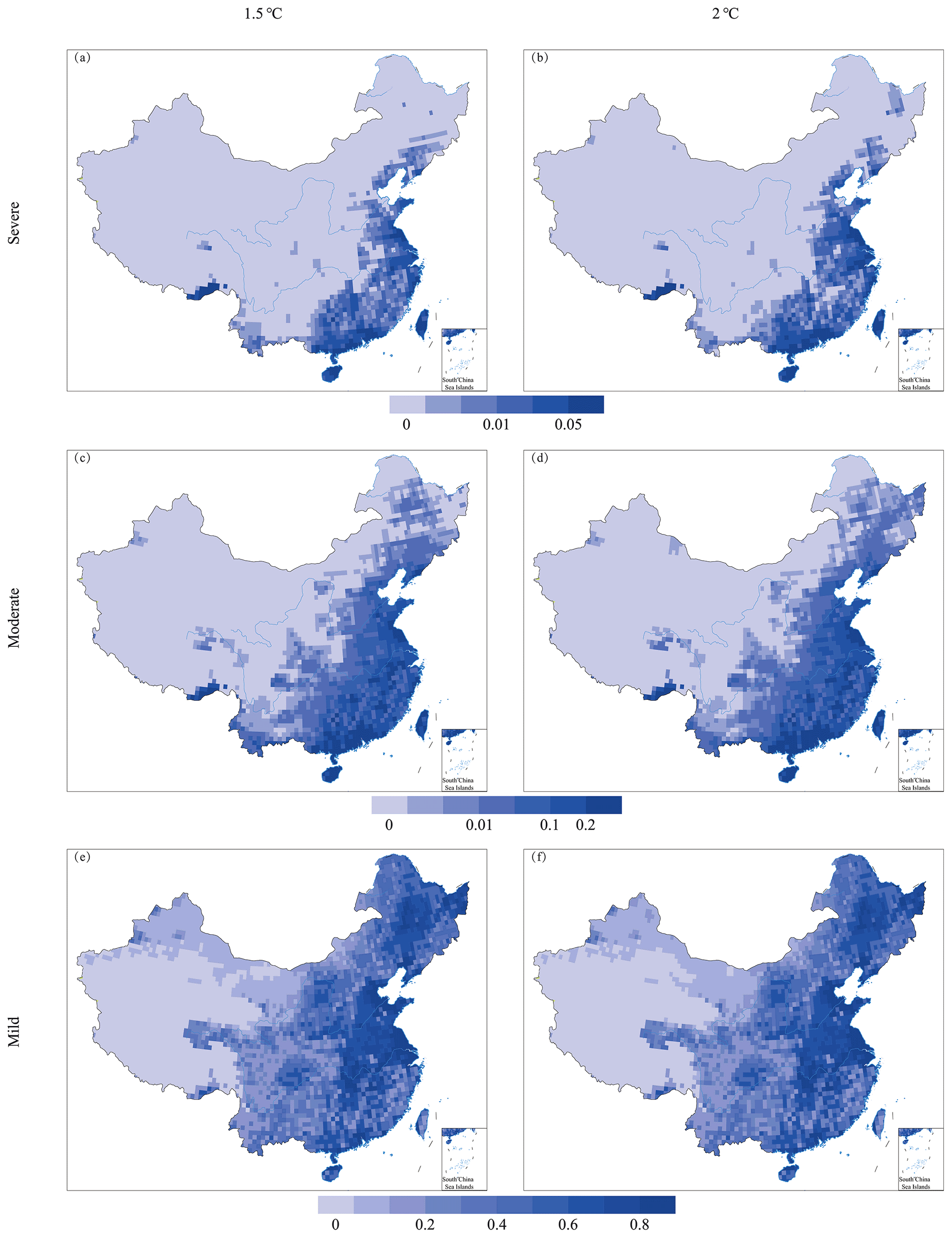

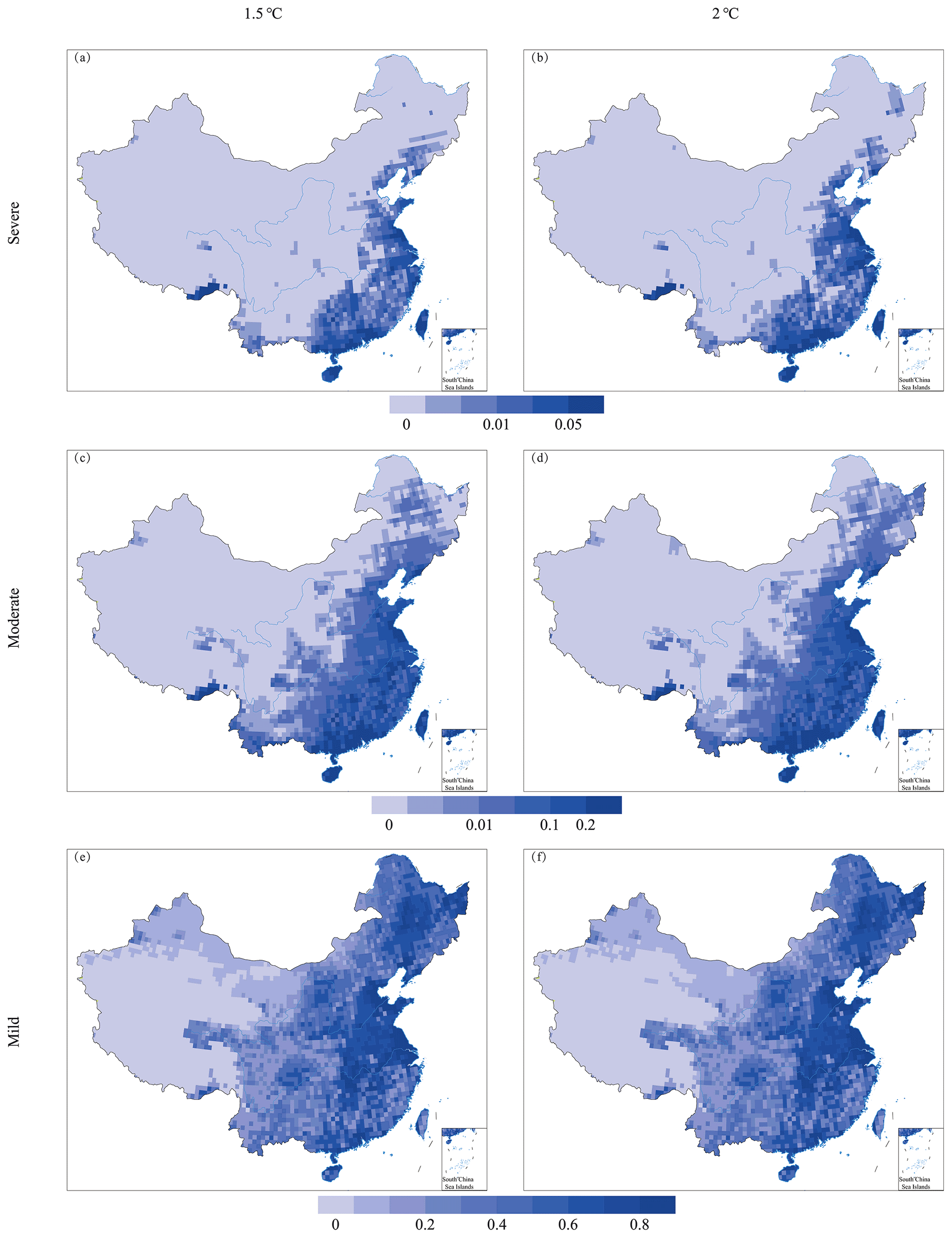

China’s Eastern Data, Western Computing Plan aims to build energy-efficient data centre clusters catering to demand-rich Eastern regions. China’s data centre clusters, including the proposed new ones, are located along its rivers. Many of these data clusters, based on flood projections by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, expected to face severe flooding if global temperatures continue on the track to increasing by 1.5°C -2°C in the coming decade.

Figure 2: Flood risk in China [Probability of severe (a–b), moderate (c–d) and mild (e–f) floods for 1.5 ∘C (a, c, e) and 2 ∘C (b, d, f) of global warming under the RCP8.5 scenario. Source]

According to the UN, developing countries in the Global South are also some of the most vulnerable to drought. India’s drought-prone regions, for instance, have increased by 57 percent since 1997. Much of the country’s data centre infrastructure is in drought-prone or flood-risk areas like Mumbai, New Delhi, Bangalore, Pune, and Chennai.

Much of the data centre infrastructure set to come online in the coming decades in many Global South countries will, therefore, be operating in resource-constrained areas, and areas at risk of severe flooding, heat, and drought.

Recommendations

Data strategies recognise that jurisdiction, while important, is not the only prerequisite for data sovereignty. Accordingly, many developing economies complement regulation with support for data centre infrastructure. Yet, these policies and strategies are hyper-focused on current demand. The politics of data sovereignty must encounter the reality of future climate change.

Given the obstacles looming on the horizon, research into greener data centres is one small part of the required response. Will hubs have enough water to sustain the demand for data centres and the basic needs of the people living there? Many data centres keep relative humidity and temperatures at more conservative levels than recommended by the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) for example, and adjustments to these parameters can, according to a study by Meta, make data centres 80 percent more water efficient. Microsoft ran a two-year experiment operating a data centre underwater, with promising results. Both sets of solutions have their hiccups: gains in efficiency can only go do far in offsetting sheer demand for data centres, and underwater data centres present unique challenges for maintenance and vulnerability to disruptions, either natural or orchestrated by unfriendly state and non-state actors.

DPI could help with the first pillar of national data centre policies mentioned in the previous section, the robustness and reliability of e-government services, by reducing data redundancy.

There is also an opportunity to weave sustainability considerations into the ongoing global conversation on digital public infrastructure. DPI could help with the first pillar of national data centre policies mentioned in the previous section, the robustness and reliability of e-government services, by reducing data redundancy. For instance, the Indian G20 presidency launched a Global Digital Public Infrastructure Repository, an open resource to help G20 members and observers sustainably build and deploy their own DPIs. With Brazil’s presidency, under the motto “Building a Just World and a Sustainable Planet”, the G20 can link DPI, sustainability, and data sovereignty.

Finally, companies and governments must invest in data centre capacity outside of “traditional” data centre hubs, to distribute the risks arising from environmental factors. National government incentives such as subsidies may be one lever to attract data centres to non-traditional hubs. This exercise must be complemented by projections of water demand and extreme weather events to make these new hubs sustainable.

Climate change will have profound implications for nascent initiatives to bolster data sovereignty, given its impact on data centres that are vital for a country's digital development. It is critical, therefore, for data centre strategies to account for the effects of an operating environment that will be very different in the coming decades.

Trisha Ray is a Resident Fellow with the GeoTech Center at the Atlantic Council

[1] Northern Virginia is the single largest data center market in the world.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV