-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

International recognition of government has always been more based on realpolitik rather than agreed upon priniciples

This is the 120th article in the series – The China Chronicles.

Read the articles here.

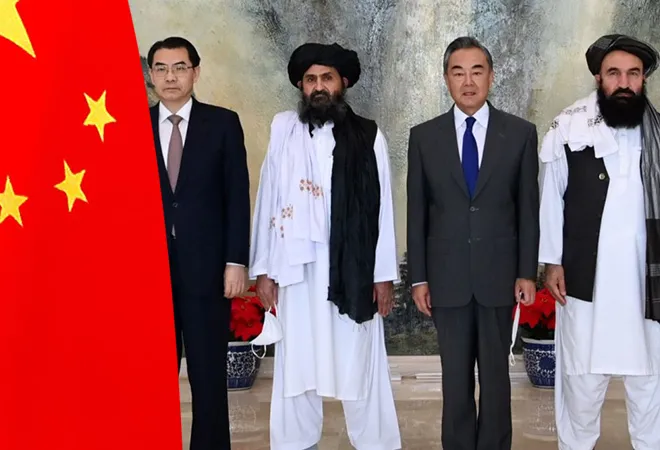

The announcement of Taliban’s interim government has raised questions for countries as to whether they should accord recognition to the new regime. China, for its part, recently endorsed the interim government stating that this was a necessary step to “end anarchy” and announced a US $31 million aid to Afghanistan. Further back in July, State Councillor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi met a delegation led by the Afghan Taliban Political Commission, Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, in Tianjin. At that time, Wang Yi acknowledged the Taliban as a “military and political force in Afghanistan” which is expected to play an “important role” in the country’s peace, reconciliation and reconstruction process. Beijing has stated in clear terms that it will respect the “sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of Afghanistan”—which indicates that China is inclined to give formal recognition to the new government.

Wang Yi acknowledged the Taliban as a “military and political force in Afghanistan” which is expected to play an “important role” in the country’s peace, reconciliation and reconstruction process.

China has also abstained from voting on a recent United Nations Security Council (UNSC) resolution on Afghanistan. This resolution demands that the territory of Afghanistan should not be used to threaten any country or shelter terrorists and expects the Taliban to adhere to its commitments and facilitate safe passage for Afghans and foreign nationals. China, however, expressed doubts about the “necessity and urgency of adopting this resolution and the balance of its content,” and noted that the amendments it had put forth were not incorporated in the final draft. Moreover, in the UNSC meeting records, Beijing’s representative Geng Shuang gave a positive assessment of the Taliban’s statement to “form an open, inclusive Islamic Government” and hoped that they would “unite all parties and ethnic groups in Afghanistan to establish a broad and inclusive political structure”.

Recognition of governments is a formal act through which one sovereign country recognises another’s claim to statehood or governance. Government recognition often looks at a two-step inquiry: One, whether the regime has effective control over the territory, and two, whether the government is a legitimate one and came to power through constitutional means. In theory, under international law, states should only recognise legitimate governments, i.e., those that have come to power on the basis of democratic institutions that recognise the people’s right to self-determination. However, in practice, recognition is either a matter of political expedience, or a move to further a diplomatic or economic agenda. Illegitimate governments that exercise effective control over a territory may be given provisional recognition, or even legal recognition, based on the political priorities of a country and its bilateral relations with the regime in question.

Illegitimate governments that exercise effective control over a territory may be given provisional recognition, or even legal recognition, based on the political priorities of a country and its bilateral relations with the regime in question.

It is interesting to note that China did not recognise the Taliban group when it had control over Afghanistan between 1996 to 2001. Back then, even though the Taliban’s government exercised effective control over the vast majority of Afghan territory, recognition to Taliban’s government was only accorded by Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and the UAE. This change in Beijing’s stance in 2021 is, perhaps, connected to the potential geostrategic and economic benefits that may arise from maintaining good relations with the Taliban—such as, ensuring Afghanistan’s participation in China’s Belt and Road initiative (BRI).

It is also questionable as to whether China would want to assess the ‘legitimacy’ requirement when granting recognition to governments. For one, it may view this as an interference in the internal affairs of a country—a principle that Beijing has historically espoused since the Panchsheel agreement, which promotes respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty. Second, China often treats norms of international law with caution and regards it as a tool that is often misused by Western countries to further their own agenda. Back in 1945, the international community, based on norms related to government recognition, refused to recognise Mao’s People’s Republic of China— which was in de facto control of Chinese territory—as the official representative of China’s seat in the UN. Under the leadership of Western countries, Chiang-Kai-Shek’s government-in-exile based in Taiwan was recognised as officially representing China until 1971.

Weighing the ‘legitimacy’ requirement would be inconsistent with China’s domestic policies towards democracy and self-determination in its autonomous territories.

Third, the requirement of legitimacy is closely associated with the neo-liberal ideals of democratic elections and self-determination. For Beijing, focusing on this requirement would also raise tough questions for its own behaviour back home—particularly with respect to its autonomous territories. For instance, does Tibet have a legitimate claim to statehood and government based on the right to self-determination of the people of Tibet? What are the legal and political implications of countries granting formal recognition to the Tibetan government in exile? Weighing the ‘legitimacy’ requirement would be inconsistent with China’s domestic policies towards democracy and self-determination in its autonomous territories.

China’s response to the recent political turmoil in Venezuela is also illustrative of this point. Juan Guaidó, the President of the Venezuelan National Assembly, proclaimed himself as the caretaker President of Venezuela in 2019. While he enjoyed democratic legitimacy, he did not enjoy effective control over the country. Many countries, including the US, have recognised Guaidó’s interim government. However, other countries like China continue to recognise Nicolás Maduro’s government and denounce what they consider as an interference in Venezuela’s domestic affairs. Beijing built strong a strong political and financial relationship with Venezuela when Hugo Chávez—Maduro’s predecessor—headed the country. China’s reluctance to recognise Guaidó’s government is based on the twin considerations of non-interference and strong bilateral relations with Maduro’s administration. However, Beijing’s support for Maduro is criticised for endorsing a government that is perceived as corrupt and inefficient.

China has effectively given de facto recognition to the SAC, agreed to fund projects, and has emphasised that its priorities continue to be stability and non-interference in Myanmar’s affairs.

More recently, a February 2021 coup ousted the elected National League of Democracy (NLD) government in Myanmar, and countries had to decide on whether they should accord recognition to the military junta. Since the military establishment has always been suspicious of Beijing, the coup has frustrated years of China’s diplomatic and economic engagement in Aung San Suu Kyi’s government. Additionally, the violence perpetrated by the military has been condemned internationally, and US and China have reportedly reached a deal to block the military junta from speaking at the UN General Assembly. While China is aware that NLD would have been a more reliable partner, it has gradually started working towards appeasing the military’s State Administrative Council (SAC) in a bid to defend its interests in Myanmar. China has effectively given de facto recognition to the SAC, agreed to fund projects, and has emphasised that its priorities continue to be stability and non-interference in Myanmar’s affairs.

Beijing’s inclination to recognise the Taliban has as much to do with the attendant benefits of forging ties with them, as it has to do with its historical approach towards international legal norms.

The concept of recognition of governments in international law is considered to be notoriously murky. China’s practice in recognition of governments do not always digress from those followed internationally, but in some cases—such as the one in Afghanistan—they are guided by the diktats of geostrategy and realpolitik. The situation in Afghanistan is in a state of flux; while Taliban is clearly in effective control of the territory, it remains to be seen if an alternative Afghan government is formed. Beijing’s inclination to recognise the Taliban has as much to do with the attendant benefits of forging ties with them, as it has to do with its historical approach towards international legal norms.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.