As the world completes almost three years of COVID-19, the virus continues to haunt airports, hospitals, markets, the global economy and people’s minds. Beijing’s ‘zero-COVID’ policy in 2022 has often faced the wrath of domestic protests and criticism from the international community for further dampening the world economy. The Chinese inability to move towards a more calibrated and targeted approach towards mitigating the pandemic, instead of such radical measures of massive lockdowns and restrictions, had added fresh blows to economic sectors ranging from retail traffic to automobile manufacturing. In November 2022, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva urged Beijing “to adjust the overall approach to how China assesses supply chain functioning with an eye on the spillover impact it has on the rest of the world.” The recent COVID surge in China, the second largest economy in the world, covering approximately 18 percent of the global GDP—has once again forced the global economic alarm bells to start ringing louder.

Changing contours of globalisation

Since 2020, if the COVID-19 pandemic has had any lesson for the global economy, it must be two-fold. Firstly, the over-reliance on the Chinese economy had to be reduced. The inextricable linkages of Chinese commodities across the Global Value Chains (GVCs) have undoubtedly given Beijing economic and political prowess. Hence, when the pandemic-induced lockdown measures had set in initially, the locking up of the market forces deteriorated the factor and product markets across the globe—a significant component of which had emanated from the supply-chain disruptions in China. As a result, countries such as the United States (US) and Japan hastened their efforts to find alternatives to manufacturing bases in China, with countries such as Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, Taiwan, and India competing among themselves to attract Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) fleeing China.

Table 1: International Policy Signals

| Country |

Policy Signalling |

| Japan |

In early April 2020, the government earmarked a stimulus package of US $2.3 billion to help its manufacturers shift production out of China to relocate to alternate locations or move back to Japan. |

| US |

Imposition of tariffs applied exclusively to Chinese goods worth US$550 billion between 2018-20. Multiple statements by former President Donald Trump suggested that American companies were to immediately search for bases other than China to avoid tariffs. |

Source: COVID-19: FDI dynamism in South and Southeast Asia, ORF

Secondly, the transportation hurdles during the pandemic provided a strong impetus for governments to shift from leveraging inter-country comparative advantages to intra-regional and domestic sufficiency in value chains. This has not only charted the path towards resilient domestic capacities but has also created several alternatives to China in sourcing both essential and non-essential commodities at competitive prices. Most importantly, countries have also become more cautious in terms of their involvement in economic groupings and multilateral platforms, adding new dimensions to globalisation trends in the post-pandemic world.

For example, in 2020, India chose not to join the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the world's largest trading bloc, to protect the interests of the robust domestic market on the one hand, and dissociate itself from the Chinese involvement in RCEP on the other. Again, the historic Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) signed between New Delhi and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in earlier 2022 is expected to help Indian exporters increase access to African and Arab markets, increasing two-way trade from the current US$ 60 billion to US$ 100 billion in the next five years.

The stringent ‘zero-COVID’ measures in 2022, with disturbing visuals ranging from people being separated from families and forced into quarantine camps to residents being trapped at home during an earthquake in the Chinese city of Chengdu, had flooded the internet.

Return of the virus affects economy

The Chinese handling of the pandemic has undoubtedly been one of the worst in the world. The stringent ‘zero-COVID’ measures in 2022, with disturbing visuals ranging from people being separated from families and forced into quarantine camps to residents being trapped at home during an earthquake in the Chinese city of Chengdu, had flooded the internet. Such human rights violations had led to mass streets protests in November that challenged the almost-impermeable ruling Communist Party. Following this, the Chinese government had to hastily ease the lockdown measures for a population with low COVID immunity leading to the resurgence of this health disaster. Only in the first 20 days of December 2022, nearly 248 million people (approximately 18 percent of China’s population) are estimated to have contracted the virus—making it the largest outbreak in the world to date.

To be sure, the magnitude of the COVID surge in China is bound to deteriorate the trade and supply chain disruptions to other countries. The timing of this outbreak adds to the criticality of the looming global economic crisis. On the one hand, while the South Asian neighbourhood is in flux—with a complete economic collapse in Sri Lanka, a military coup and huge unemployment situation in Myanmar, inflation and volatility of domestic currency in Bangladesh and India, political turmoil and financial emergency in Pakistan and widening trade deficits and declining FOREX reserves in Nepal; on the other hand, the Ukraine-Russia conflict has thrown the energy markets into a complete mess in several Global South nations. Additionally, supply cuts by edible-oil exporting countries and the impact of energy price rise on food prices have made food security a major concern, especially for the financially vulnerable sections of society.

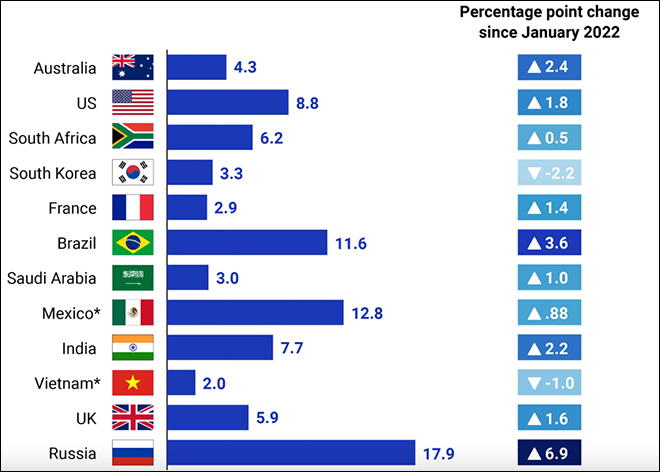

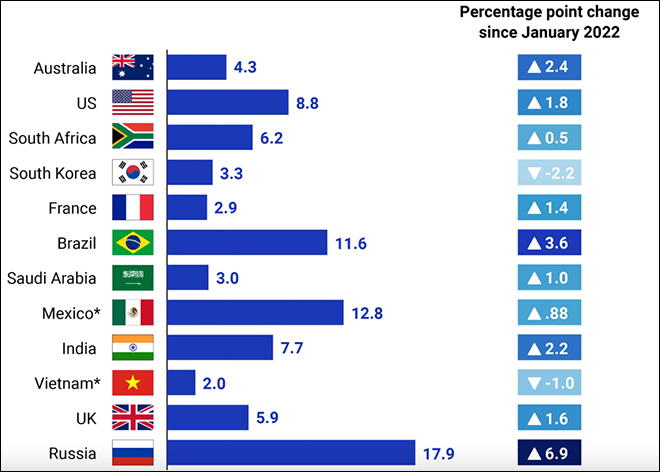

Figure 1: Annual Increase in Food Inflation in select countries, as of March 2022 (in percentage)

Source: Trading Economics | *Data from Mexico and Vietnam is from April 2022

Source: Trading Economics | *Data from Mexico and Vietnam is from April 2022

Quite evidently, the slowdown in the Chinese economy in 2022 has made the global economy quite vulnerable. While the slump in domestic demand had hurt foreign exporters, the strict lockdown measures had detrimentally impacted the supplies to manufacturers, especially in other Asian countries. On top of this, the inflationary pressures in US and Europe, along with the rising interest rates and a looming economic recession, have cracked open the fault lines of the complex interplay of global macroeconomic parameters. Adding fuel to this fire is the current health emergency in China, which will end 2022 on a somewhat nervous note for the world economy.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV