-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The recent banking crisis in Henan throws light on the corruption that is rampant at the lower rungs of the Chinese bureaucracy.

The Chinese idiom ‘tiān gāo, huángdì yuǎn’ (The heaven is high, the emperor is far away) is as relevant in modern China as it was during the Yuan dynasty, during whose reign the saying is said to have originated. The expression epitomises the untrammelled power that is vested in the bureaucracy that is far away from the Beijing central leadership as seen in the manner in which local officials have dealt with the demonstrations in the wake of the crisis of rural banks in Henan province.

Trouble began in April after banks in Henan and Anhui—Yuzhou Xinminsheng Village Bank, Shangcai Huimin County Bank, Zhecheng Huanghuai Community Bank and New Oriental Country Bank of Kaifeng and Guzhen Xinhuaihe Village Bank—denied depositors access to their funds.

Bank depositors were assaulted by unidentified men during a protest on 10 July in central Henan province. Around 1,000 demonstrators had gathered outside a branch of China’s central bank in Zhengzhou city, appealing to the authorities to defreeze their accounts in rural banks. Trouble began in April after banks in Henan and Anhui—Yuzhou Xinminsheng Village Bank, Shangcai Huimin County Bank, Zhecheng Huanghuai Community Bank and New Oriental Country Bank of Kaifeng and Guzhen Xinhuaihe Village Bank—denied depositors access to their funds. While Chinese officials have not revealed the amount of money in the banks that has been frozen, an estimate by the South China Morning Post puts the figure at US $1.5 billion. Getting people to put their money in these banks did not seem like a hard sell, considering that a five-year deposit offered by these small rural banks through online third-party platforms fetched an annual interest between 4.1 percent and 4.5 percent. Thus, customers saw the prospects of their money grow faster as compared to other state-owned lenders such as the Bank of China where a five-year deposit fetches 2.75 percent interest. There are as many as 4,000 small banks across the country. In 2021, China’s central bank instructed these lending institutions to refrain from securing deposits from across the country using internet platforms. These curbs aimed to reduce the potential of small banks from attracting business from areas away from their home turf.

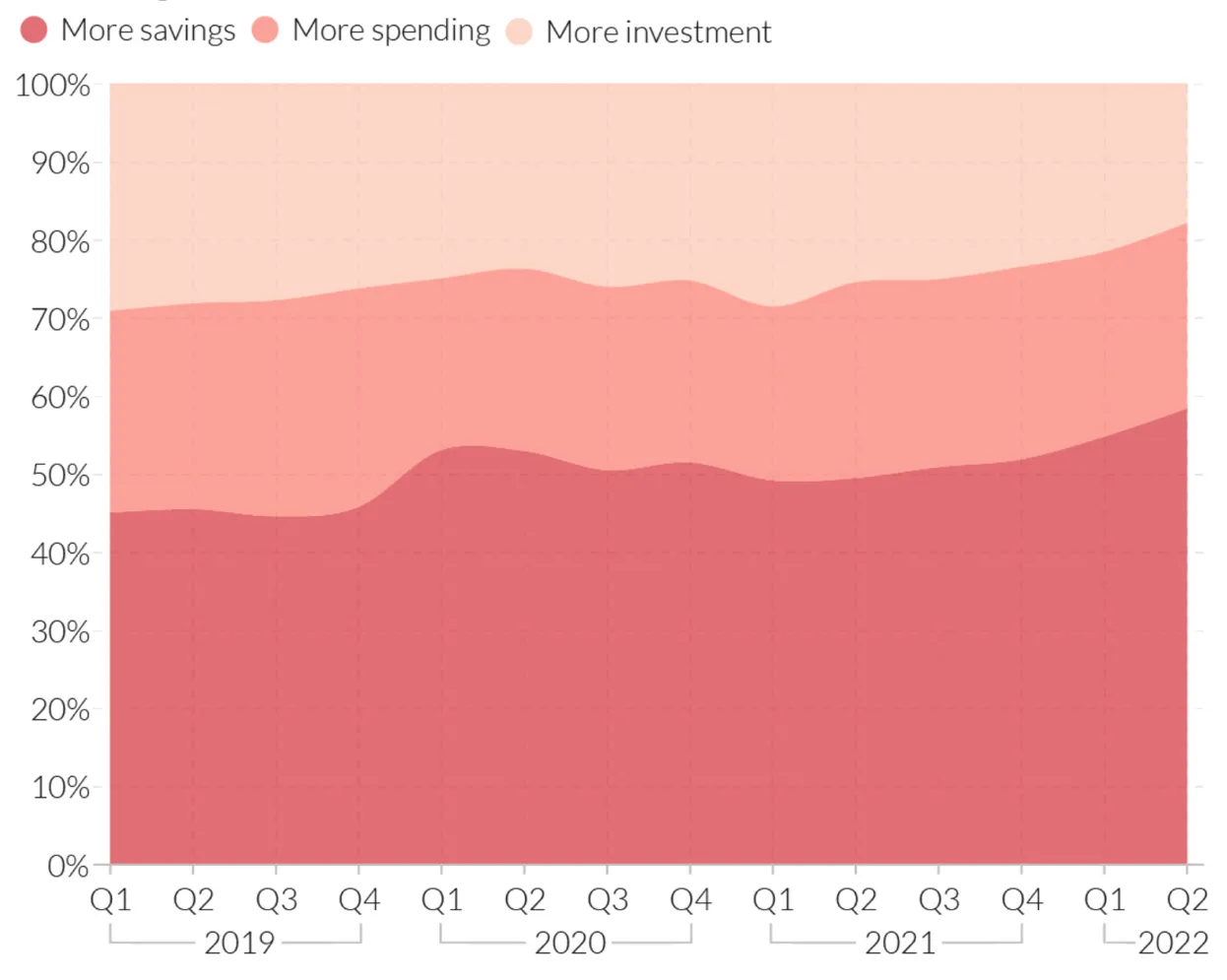

Farmers and small entrepreneurs turn to rural banks for their borrowing requirements, but these institutions are seen to be more vulnerable during downturns. In addition to that, the anticipation of more outbreaks and consequent lockdowns has weighed down on the job market. This year, more than 10 million youngsters are expected to graduate making the struggle for jobs even more intense. China’s unemployment rate is likely to reach 2020 levels due to the pandemic-prevention measures in place. The findings estimate that the number of unemployed Chinese in mid-2020 could have been around 92 million, which is almost 12 percent of the nation’s working population. In such times, people prefer to save and hoard cash. A survey by China’s central bank of bank depositors residing in urban areas revealed that their belief in future earning potential was at the lowest level since early 2020. More than 58 percent of the respondents voiced the need to maximise savings (Refer to the graphic below).

Source: People's Bank of China Statistics, Sixth Tone

Source: People's Bank of China Statistics, Sixth Tone

This anxiety to stash cash to tide over contingencies may also have contributed to a run on the banks, which in turn, revealed the weaknesses of these financial institutions.

Meanwhile, given the adverse press due to the protests, the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission has gone into damage control and started paying people with deposits of up to 50,000 yuan (US$7,450). But the incident has raised questions regarding Beijing’s writ over the local officials and the efficacy of President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign. First, local officials gamed the health-code system instituted in the wake of the pandemic to ensure that many of the banking crisis victims could not take part in the protests. While some officials are being punished, they face a mild disciplinary rap.

The fact that this criminal triad acted with impunity and evaded capture for nearly a decade shows the extent of collusion between organised white-collar syndicates and local officials.

Second, the footage leaked on social media, which shows unidentified men attacking the banking crisis victims in the presence of police personnel, has led to an outrage. In her book ‘Outsourcing Repression: Everyday State Power in Contemporary China’, author Lynette Ong argues that local officials use non-state agents to enforce their writ on a recalcitrant population which is usually hidden from the media glare. The lengths to which local authorities have gone to suppress the banking crisis points to a larger malaise and divergences. This is at a time when President Xi Jinping has termed economic stability a top priority and promised to improve oversight within the state-dominated financial system. At the December 2021 Central Economic Work Conference—an important meeting of China’s ruling elite that sets the agenda in the financial sector—the official release mentioned the word ‘stability’ 25 times. The Chinese Communist Party resolved to control the negative role of capital. Han Wenxiu, Executive Deputy Director of the General Office of the Central Financial and Economic Affairs Commission mooted the concept of a ‘traffic-lights’ system in effect earmarking areas where it could be encouraged, and those sectors where capital could be allowed with some restrictions, or completely banned. Third, police investigations have revealed that the criminal gang headed by Lu Yi took control of the banks using an investment firm, and then transferred out money on the pretext of bogus loans. The investment firm was in cahoots with bank officials, online platforms, and brokers to lure deposits from customers via online platforms. The criminal gang behind the banking crisis had been operating since 2011, and Lu Yi is said to have fled China. The fact that this criminal triad acted with impunity and evaded capture for nearly a decade shows the extent of collusion between organised white-collar syndicates and local officials. Lastly, Xi’s much-vaunted campaign against corrupt officials was an acknowledgement of the fact that high-handedness on part of the authorities coupled with triggers like unemployment and graft toppled regimes in Africa and West Asia. Footage shows bank depositors brandishing placards that read “No deposits, no human rights” and“We stand against Henan government’s corruption and violence”. The ham-handed approach of Henan provincial officials shows they seem to be working to undo the supposed gains of Xi’s campaign. In China’s case, financial security is connected to its national security. Xie Maosong, a political scientist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, posits that the CCP’s inability to control and mitigate financial risks, in turn, endangers the stability of its regime. Xi has rightly singled out graft as the biggest risk for the CCP and urged regulators and other agencies to improve oversight and governance in the financial sector. The focus of Xi’s anti-corruption campaign has been to net the ‘tigers’ in the financial sector. In CCP parlance, the tiger is code for a senior cadre, but does the excessive spotlight on them mean that ‘flies’ (lower-rung officials) can stay in place and do greater damage? This is a question that the party must ponder over.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Kalpit A Mankikar is a Fellow with Strategic Studies programme and is based out of ORFs Delhi centre. His research focusses on China specifically looking ...

Read More +