With the threat of large-scale unemployment looming over its already plunging economy, which has reportedly contracted by 6.8 percent, China is looking at novel avenues of generating jobs. It is firing on all cylinders to generate employment in formal and informal sectors.

Since the 1978 reforms and rapid economic transformation, more than 850 million people have been brought out of poverty. However, the per capita income of Chinese citizens is 25 percent of their counterparts in high-income nations.

Immediately after becoming the nation’s President in 2013, Xi Jinping had set 2020 as the deadline to eradicate absolute poverty. However, the pandemic seems to have impacted the household incomes with China’s Premier Li Keqiang admitting that employment is the “biggest issue,” and the challenge of eradicating deprivation may get increasingly “heavier since people may slip back into poverty.” In April, the International Monetary Fund estimated that China would notch a growth rate of 1.2 percent this year.

Immediately after becoming the nation’s President in 2013, Xi Jinping had set 2020 as the deadline to eradicate absolute poverty.

This has forced China’s rulers to scour out-of-the-box solutions for a variety of reasons. Firstly, as many as nine million youngsters are expected to graduate this month. Campus recruitment normally takes place around the time of the spring-festival holiday (January-February). But the government had ordered a closure of varsities to tackle the contagion, throwing the recruitment process off gear. Private firms have deferred new hiring and, in many cases, laid off staff. Economists estimate that urban unemployment may touch 10 percent in 2020.

China’s ruling elite prize “social stability” and is acutely intuitive to the demands of the nation’s burgeoning educated class. In the late-1980s, lack of jobs among other issues spurred the student unrest, which ultimately culminated in the Tiananmen incident. Discontent is brewing with the trading community, which hit the streets recently in Wuhan, demanding reduction in rentals.

The government is roping in state-owned entities to tide over the job crisis. The Chinese government manages 51,000 state-owned enterprises (SOEs) that have a total workforce of 20 million. State refiner Sinopec is among the SOEs that are hiring in large numbers and universities could allocate an extra 2,00,000 seats for graduate studies.

In the late-1980s, lack of jobs among other issues spurred the student unrest, which ultimately culminated in the Tiananmen incident.

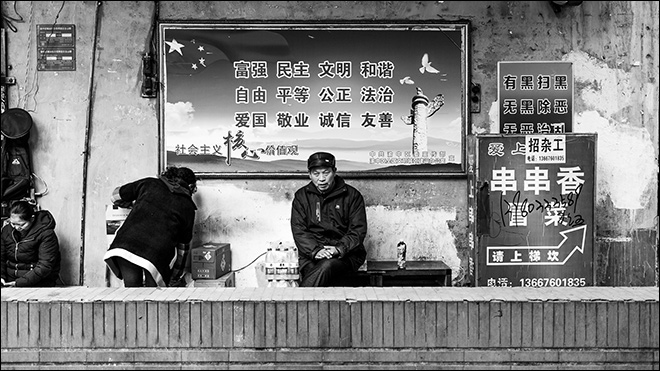

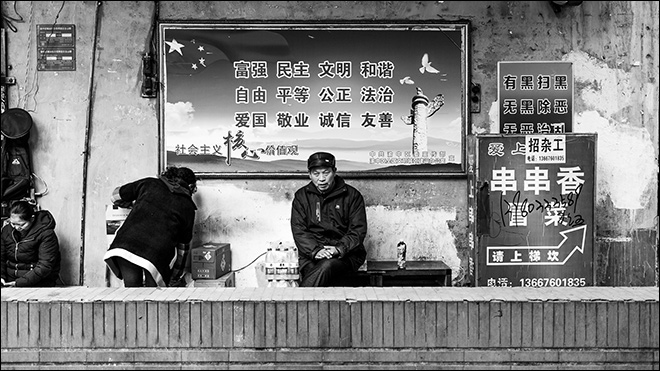

China is also looking back into history to tap its hallmark ‘stall economy’ for its low-middle class population. It will be borrowing from the phase where vendors used handcarts in the 1980s to sell small wares, which eventually set out to become baby-steps towards China’s ‘socialist market economy’ of the 1990s. This, China hopes will help the nation’s low-income segment that constitutes around 600 million of the population, and which might slip back into poverty if not given a push.

The clarion call first came in May 2020 from the top leadership at the ‘two sessions’ — the annual conclave of China’s parliamentarians. Premier Li Keqiang hailed the Chengdu experiment of allocating around 36,000 street-vending pitches that created over 100,000 jobs immediately. Most of these handcart vendors sell eatables, apparel, and inexpensive electronic goods. Few weeks later, Li heaped praise on owners of handcarts and said the “street-stall economy is a major source of employment and part of China's vitality.”

At the conclave, Li had also announced a RMB 4 trillion ($560 billion) rescue package. While this may assuage the blue-ribbon corporates, a large section of blue-collared China seemed to have been clutching at the straws.

By speaking on behalf of the lower-middle class, Li has underscored China’s conflicting narratives emerging in the wake of the pandemic: What represents the nation?

By speaking on behalf of the lower-middle class, Li has underscored China’s conflicting narratives emerging in the wake of the pandemic: What represents the nation? The glitzy towers and technology hubs in Shenzhen, Shanghai or Beijing? Or grimy street vendors peddling their wares in back alleys hiding away from the omnipresent gaze of law-enforcement officials?

Zhou Tianyong, an influential economist and director of the China Strategy and Policy Research Center of Northeast University of Finance and Economics, has estimated that as many as 50 million jobs can be created if the government gave more space to vendors and farmers selling their produce.

This marks an important policy shift in smaller cities as till recently the people who constituted the informal sector were categorised as “low-end population,” and civic authorities routinely tore down markets where the vendors peddled their merchandise.

China’s ‘opening up and reform’ initiative in the late 1970s began from dismantling the Maoist command economy and the lifetime employment culture.

The call for reviving the street-stall economy is ‘back-to-basics’ of sorts. China’s ‘opening up and reform’ initiative in the late 1970s began from dismantling the Maoist command economy and the lifetime employment culture.

There have been success stories of entrepreneurs who literally started off from the streets. A young man hawked merchandise in the back alleys of the Zhejiang province, and this helped him understand the intricacies of the retail business. Today, the same man, Jack Ma, presides over a $500 billion e-commerce conglomerate called Alibaba. Before he founded Huawei — the world's largest manufacturer of telecom equipment — Ren Zhengfei is said to have vended fire extinguishers.

The call for reviving the street-stall economy is ‘back-to-basics’ of sorts. Image © Gauthier DELECROIX ― 郭天/Flickr

The call for reviving the street-stall economy is ‘back-to-basics’ of sorts. Image © Gauthier DELECROIX ― 郭天/Flickr

Moreover, today’s street-stall vendors are unlike the dodgy salesmen of the yesteryears. Thanks to the digital payment revolution in China, buyers pay for their purchases via smartphones, which helps in tracking down the vendors in cases of refunds or other issues.

While the jury may be out on Li’s call to boost the “street-stall economy,” he is getting plaudits from some sections for speaking up for the nation’s low-income segment that constitutes around 600 million of the population. There are nascent signs that the market is responding to the clarion call. Alibaba and JD.com have offered financial support in the form of loans to street vendors.

Today’s street-stall vendors are unlike the dodgy salesmen of the yesteryears. Thanks to the digital payment revolution in China, buyers pay for their purchases via smartphones, which helps in tracking down the vendors in cases of refunds or other issues.

Stocks of companies that sell stall economy ancillaries have risen. For example, SAIC-GM-Wuling Automobile launched a new prototype of cargo van that can be converted into a mobile stall early this month. The announcement sent the company’s shares listed on the Hong Kong stock exchange surging by 120 percent.

Local administrations in some cities across China are making changes to rules — ranging from easing controls over mobile stalls in Shanghai and Chengdu, giving free areas for vendors in Chongqing to inviting hawkers to resume businesses in designated hawking areas of Ruichang in Jangxi.

However, there is resistance to Li’s endorsement of the informal economy. The Chinese Communist Party's Beijing Municipal Committee slammed the proposal in its newsdaily, terming handcarts unclean and said it would give the nation’s capital a shabby look. In such condemnation, many observers have speculated a factional feud brewing right at the top of China’s tiny ruling elite. Incidentally, Beijing’s administration is controlled by party secretary Cai Qi, who sits on the Politburo and is said to be a close ally of Xi. Under Xi Jinping’s leadership the “collective leadership” principle remains on paper. Xi has instituted many ‘leading groups’ and presides over all of them. The leading groups, which drive policy on a range of issues like the economy’s management, diplomacy among others, put Xi at the apex of policymaking.

Under Xi Jinping’s leadership the “collective leadership” principle remains on paper.

Traditionally, China’s Premier has been tasked with the day-to-day management of the economy, but the ‘leading groups’ strategy seemed to be elbowed out Li, who is an economist by training. The pandemic, however, seems to have forced a rethink with Xi ceding power, and putting Li at the helm of combating the coronavirus outbreak. However, Xi would not want Li, who has experience in tackling the 2009 H1N1 virus outbreak, to garner an image as the hero of the current public health crisis. Hence, Xi’s allies have picked holes in the call to revive the stall economy. The National Bureau of Statistics has expressed reservations on the numbers trotted by Li, and the official media downplayed Li’s efforts.

Deng Xiaoping, the man who pioneered China’s reforms, famously said its economic transformation was the outcome of “crossing the river by feeling its stones,” implying there was no clear roadmap or a masterplan.

Today, China along with other nations across the world, including India, is seen grappling with the issue of how to effect an economic recovery after the pandemic’s devastation has subsided.

Xi would not want Li, who has experience in tackling the 2009 H1N1 virus outbreak, to garner an image as the hero of the current public health crisis.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s comment in 2018 regarding the job-creating capacity of small entrepreneurs that are into the business of selling potato fritters (pakodas) was met with derision, and so was his message that there was potential in micro-businesses.

In the ‘stall economy’ model lie some sharings for policymakers in India who are also facing the quandary of how to kickstart the Indian economy — it is important to recognise the informal sector’s potential.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

The call for reviving the street-stall economy is ‘back-to-basics’ of sorts. Image © Gauthier DELECROIX ― 郭天/Flickr

The call for reviving the street-stall economy is ‘back-to-basics’ of sorts. Image © Gauthier DELECROIX ― 郭天/Flickr PREV

PREV