-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Thucydides’ assertion of the fifth century war being “inevitable” owing to the “rise of Athens” and the fear it “instilled” in the “ruling” power of Sparta — holds key relevance in the 21st century.

In 2015, the Harvard Belfer Center, under the tutelage of noted power transition theorist Graham Allison, studied 16 historical cases of “ruling” and “rising” powers. The study propounded 12 of the 16 adopted cases within the past 500 years to have eventually devolved into war — offering a stark endorsement of the ‘Thucydides trap’. It is named after the Greek historian Thucydides, whose account of the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta continues to be a seminal piece of work on the theory of power transitions. And if the United States’ unprecedented show of strength during President Donald Trump’s recent visit to Asia is an indication, Thucydides’ assertion of the fifth century war being “inevitable” owing to the “rise of Athens” and the fear it “instilled” in the “ruling” power of Sparta — holds key relevance in the 21st century.

The post-Cold War world has witnessed China’s meteoric rise. In 1984, five years after the Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms, America’s share of the world economy was 12.8 times that of China. By 2016, that ratio plummeted to 1.7 times. In 1996, five years before China’s accession to the World Trade Organisation, US trade with the world was 3.9 times that of China. By 2010, China had become the world’s largest trading nation. In recent years, China’s GDP has swelled nearly five times — from $2.3 trillion in 2005 to $11.2 trillion in 2015. China’s economic rise has also translated into greater security maximisation. Its defence budget increased from a mere $52 billion in 2001 to $214 billion in 2015 (Read). In comparison, the US continues to hone its primacy with respect to its economy — GDP (2016 absolute terms) of $18.62 trillion at current prices (Read). Militarily, the United States in the post-Cold War era has consistently accounted for over one-third of the world’s total military expenditure (Read). Lastly, globalisation continues to be a euphemistic outlet for America’s soft power expanse. Benjamin Barber once referred to it as MTV, Macintosh, and McDonalds: “pressing nations into one homogenous global theme park.” Today, the same may have diffused into the multiples of Netflix, Facebook and Starbucks; globalisation nevertheless remains bedrocked by the fundamentals of American soft power. However, China’s rise has fanned neorealist prophecies of a coming power transition war between the “rising” power of China and the “ruling” power of the United States.

Globalisation continues to be a euphemistic outlet for America’s soft power expanse. Benjamin Barber once referred to it as MTV, Macintosh, and McDonalds: “pressing nations into one homogenous global theme park.”

The same stands evidenced in Chinese and American security policy corridors’ discourse on China’s Anti-Access Area Denial (A2AD) strategies and its American corollary of the Air-Sea Battle (ASB) doctrine. From the Thucydidean standpoint, Graham Allison thus deemed the “the preeminent geostrategic challenge of this era” to be the “impact of China’s ascendance.” In the Trump era, this “challenge” stands greatly exacerbated due to increased American militarism stemming from the US foreign and security establishment’s fixation with sustaining US “credibility”.

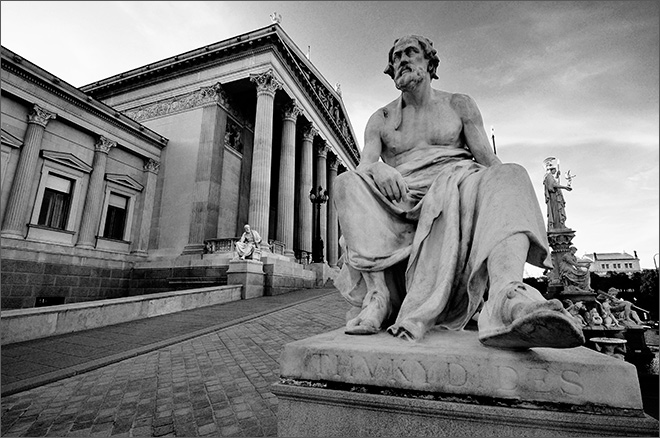

The statue of Thucydides, Vienna | Photo: Chris JL/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The statue of Thucydides, Vienna | Photo: Chris JL/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The Peloponnesian war between the “rising” power of Athens and the “ruling” power of Sparta can be traced to either parties’ entrapment with their alliance commitments. When the city-states of Corinth and Corcyra/Corfu sparred, Sparta rushed to its ally Corinth’s defence fearing the wane of its own influence — by extension, in the probability of its ally’s loss. This left the “rising” power of Athens “little choice but to back” its ally Corfu. In the pedagogy of alliance politics (à la Glenn H. Snyder), credibility stands central for alliance partners to effectively balance between fears of abandonment and perils of entrapment. In deterrent cases, sustaining credibility within alliances is a virtue of positive peace. In other cases — as enunciated in case of Sparta fearing a decline of its influence — following through on commitments to sustain one’s influence (by extension), can be a catalyst for escalation ending in strategic disasters. Thus, noted scholar Joseph Nye’s assertion of politics being “a contest of competitive credibility” holds seminal pertinence.

In case of the United States, which has served as the sole military superpower in the post-Cold War world with security partnerships with over 60 countries, many of its strategic missteps have stemmed from its fixation with “credibility”. In the heydays of the Cold War, the United States — in its zeal to contain the Soviet Union — engaged in a limited intervention in the then-French Indo-China. In the years to come, that limited intervention, in a bid to sustain American “credibility”, devolved into the all-expansive Vietnam War, which by late 1968 forced Washington to engage over half a million troops in the region, spend approximately $35 billion annually, leaving over 50,000 US soldiers dead.

In an interview with The Atlantic in 2016, President Barack Obama expressed his disdain for the US foreign policy establishment’s “fetish” with credibility — especially the “sort of credibility purchased with force.” President Obama, however, had his own share of fixation with credibility in his first term — best evidenced in his insistence to not “brush aside America’s responsibility as a leader” in case of the West’s intervention in Libya. The subsequent US military operation reduced Libya to an active breeding ground for religious extremists and terrorist networks. Having learnt the pitfalls of this credibility “fetish”, President Obama in his second term refrained from militarily intervening in Syria. In national security meetings, President Obama would often nip arguments for employing force with the assertion that “dropping bombs on someone to prove that you're willing to drop bombs on someone is just about the worst reason to use force.” Regardless of this wisdom that befell the 44th president in case of Syria, fixation with American credibility — underpinned by the imperatives of America’s supposed “responsibilities” as the world’s sole “indispensable” power — has been a regular fixture in US foreign policy.

Having learnt the pitfalls of credibility “fetish”, President Obama in his second term refrained from militarily intervening in Syria. In national security meetings, President Obama would often nip arguments for employing force with the assertion that “dropping bombs on someone to prove that you're willing to drop bombs on someone is just about the worst reason to use force.”

In case of the Asia-Pacific, where the US boasts the exceptionality of its ‘hub & spokes’ alliance system (à la David Shambaugh), overt fixation with American credibility is reinforced by its expansive conception of interests in the region. Consider the 2017 Annual Report to Congress on ‘Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China’. Submitted by the US Department of Defense, the report asserts that the US would ensure it “retains the ability to defend the homeland, deter aggression, protect our allies and partners, and preserve regional peace, prosperity, and freedom.” Such expansive conceptions can have grave consequences in terms of perpetuating what Barry Posen refers to as activist grand strategies’ preeminent feature of “domino theories”. In case of the US, Posen defined the same as foreign and security policy discourses that string together a chain of "individually imaginable, but collectively implausible, major events, to generate an ultimate threat to the United States and then argue backward to the extreme importance of using military power to stop the fall of the first domino.”

In the Trump era, the excesses of “domino theories” is compounded by the US foreign and security establishment overcompensating for the Trump administration’s policy incoherence with greater military posturing to reassure allies and partners in the region — and by that extension sustain US “credibility”.

Consider President Trump’s recent five-nation visit in the Pacific Rim. In Japan, he bonded with Prime Minister Shinzo Abe who in the recent snap elections enjoyed a decisive endorsement of his revisionist vision for the pacifist country. In South Korea, after attempting to alleviate Seoul’s concerns with a fairly-tempered speech at the Korean National Assembly, President Trump irresponsibly volleyed insults at North Korea’s Kim Jong Un. In Vietnam, he accused the region’s countries of trade malpractice, and pledged to “always put America first.” In the Philippines, he once again expressed his affinity for authoritarian leaders by reportedly appearing “sympathetic” towards President Rodrigo Duterte’s violent war on drugs, and bonded with the Filipino strongman over their shared dislike for President Barack Obama. In China, President Trump failed to address Beijing’s human rights record, and showered President Xi Jinping with “embarrassingly fawning accolades” — to borrow former National Security Advisor Susan E. Rice’s words.

In the Trump era, the excesses of domino theories is compounded by the US foreign and security establishment overcompensating for the Trump administration’s policy incoherence with greater military posturing to reassure allies and partners in the region — and by that extension sustain US credibility.

Meanwhile, the US Department of Defense was engaging in an unprecedented show of force. The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Joseph Dunford even downplayed the significance of the overlapping timelines as mere “coincidence”. Nearly a fortnight before President Trump’s arrival in the region, the US Navy on 24 October 2017 announced the arrival of the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt along with its Carrier Strike Group (CSG) in the “Indo-Asia-Pacific Region”. The same was set to join USS Ronald Reagan — the US 7th Fleet’s “only forward-deployed carrier strike group” in the region generally operating out of Yokosuka Naval Base in Japan — then anchored off the port of Busan in South Korea. A day later, the “scheduled deployment” of the aircraft carrier USS Nimitz in the region was also announced. Along with its Carrier Strike Group, the USS Nimitz was set to arrive in the region after “concluding operations in US 5th Fleet” in the support of Operation Inherent Resolve — codename for US-led coalition operation against the Islamic State.

Photo: Andrea Hanks

Photo: Andrea Hanks

In perspective, the last time the United States had three aircraft carriers in the region was a decade ago off the coast of Guam — miles away from the volatility of the East China Sea and the Korean peninsula. These deployments rendered the US Navy to have seven out of its total 11 nuclear aircraft carriers to be “underway simultaneously for the first time in several years.” Further, a day before the arrival of the aircraft carriers was announced, the US Air Force also reported a ‘first time in several years’ escalation. The US Air Force Chief of Staff General David Goldfein told the security news website Defense One that the Air Force was updating B-52 bombers armed with nuclear warheads to the 24-hour alert status — a “ready-to-fly posture not seen since the Cold War.” Although the US Air Force later reneged on this announcement of escalation, the run-up to Trump’s visit oversaw the first operational deployment of the F-35A fifth generation stealth fighter in the region, and increased frequency of ‘show of force’ operations by long-range B1-B Lancer strategic bombers.

Although all aforementioned deployments were underplayed as “scheduled” deployments, CNN military analyst and a former US Navy admiral John Kirby said the deployments were meant to send a message of “making sure China knows it’s

In Beijing, the message intended by this uptick in US military posturing has not only been received, but has also acquired the Asian giant’s ire. This week, a Hong Kong daily reported that China held a “large-scale military exercise” in the region “in response” to the arrival of three US aircraft carriers in the region. It is crucial to note that such precedents of military posture escalation raise the prospects of miscalculations that may serve as tripwires to greater military confrontations — probably of Thucydidean proportions — between China and the United States.

In his farewell address in 1796, George Washington warned against “interweaving our destiny” with that of other countries to “entangle” American “peace and prosperity” in exchange. Certainly there exists no medium to ascertain if Washington was a proponent of American isolationism. However, the founding father’s words over two centuries later stand pertinent in context of American interests swelling in perpetuity in view of American foreign policy being “entangled” with missions meant to convey its “credibility”. The United States under Trump thus needs to take note of the writings on the Thucydidean wall, if it wishes to avert its now increasingly plausible tryst as a “ruling power”.

The author is a Research Fellow at Observer Research Foundation, Mumbai.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Kashish Parpiani is Senior Manager (Chairman’s Office), Reliance Industries Limited (RIL). He is a former Fellow, ORF, Mumbai. ...

Read More +