This is the forty ninth part in the series

This is the forty ninth part in the series The China Chronicles.

Read all the articles here.

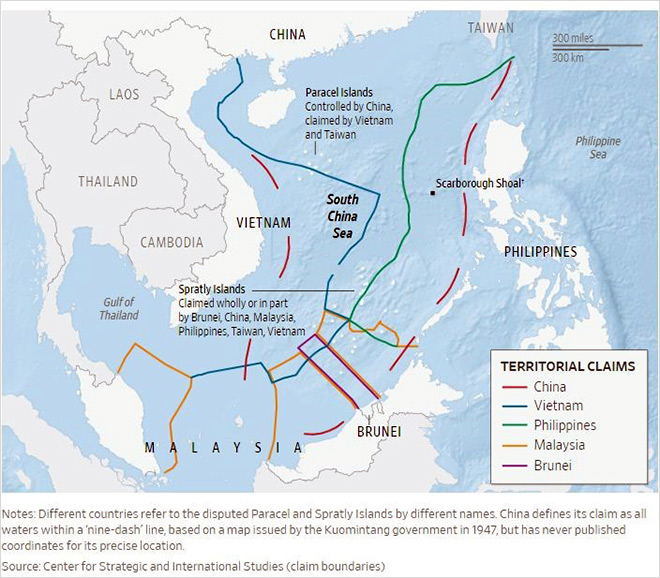

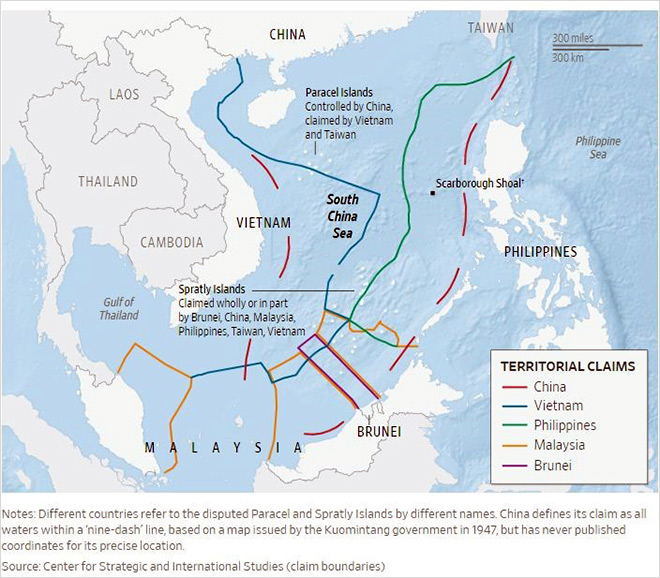

China’s assertive stance in regard to its territorial disputes in the

South China Sea (SCS) (Figure 1.1) and the

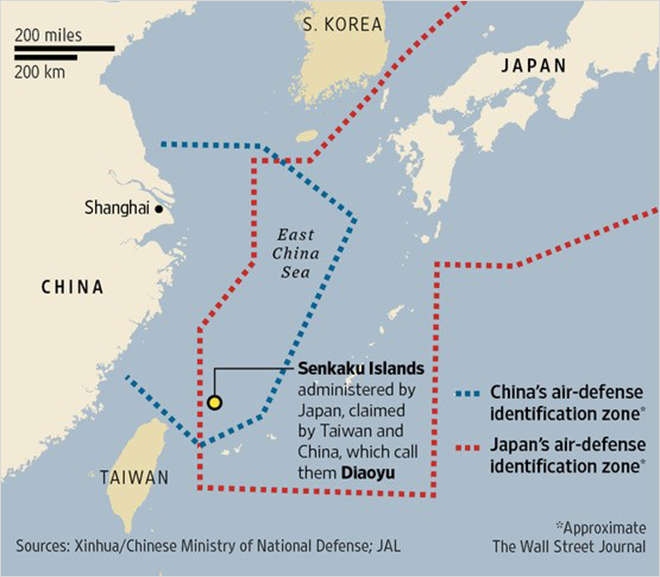

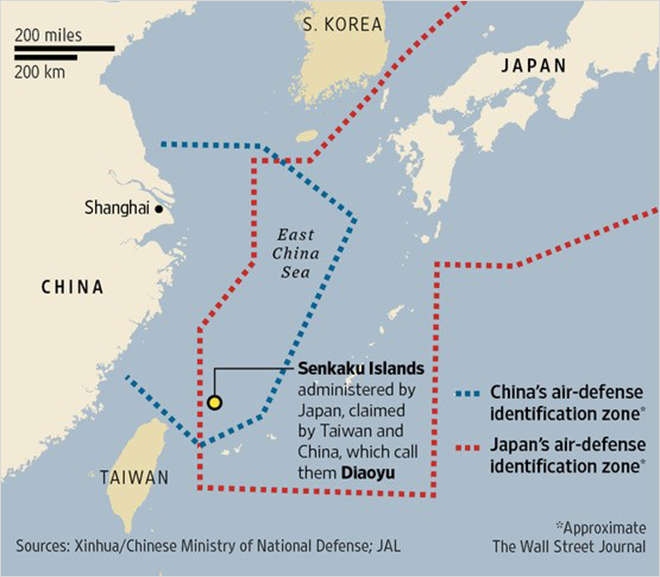

East China Sea (Figure 1.2) has considerably strained relations with its immediate neighbours and regional naval powers. The growing prospect of a

naval compact in the Indo-Pacific confirms the impression that China’s impact, as a rising naval power of Asia has been deleterious for the region. The main concern behind the rapid development of Chinese naval forces — the People's Liberation Army Navy’s (PLAN) and the Chinese Coast Guard (CCG)) is its implication on the freedom of navigation in international waters and its accompanying economic prosperity, peacefulness as well as ideational stability or legitimacy. There is increasing concern about Chinese actions restricting maritime rights and access to common resources. These factors place China’s maritime ambitions at the heart of both theoretical and more practical discourses of Asian security. While classic security dilemma theorists will allude the naval build-up to the substantial presence of the United States Navy in the area, the real motivation behind the rise in Chinese naval activity can be attributed to

Chinese nationalism.

Figure 1.1 — Territorial claims between China and other Southeast Asian nations in the South China Sea. | Source

Figure 1.1 — Territorial claims between China and other Southeast Asian nations in the South China Sea. | Source

Figure 1.2 — Territorial dispute over the Senkaku islands in the East China Sea. | Source

Figure 1.2 — Territorial dispute over the Senkaku islands in the East China Sea. | Source

Chinese nationalism

Since the mid-1860s, Chinese political discourse and its accompanying foreign policy has gone through a series of transformations. A Chinese nation that was once considered the leader of the Orient was severely weakened by continuous disruptions like the Opium Wars, the Boxer Rebellion and the Sino-Japanese War. Consequently, these events also caused a dent in the nationalist pride and the Chinese people suffered various atrocities during this period. The rejuvenation of Chinese economy in the past three decades has helped the Chinese nation regain their lost prestige. The Communist Party of China (CPC) has taken advantage of this rising nationalist sentiment to unite a fragmented Chinese society as this supplies the state the requisite authority to pursue prestige and legitimacy in the international arena. A key component of this prestige, one fueled by China’s nationalistic ambitions, is a substantial naval force. Naval power lies at the centre of Chinese aspirations and coalesces energy security, maritime strategy, territorial integrity, naval nationalism, foreign policy, power projection and regional leadership. China of today doesn’t fit the definition of an actual communist state; rather it has transformed into an authoritarian oligarchic state with mixed economic principles where nationalist sentiment weighs heavy on the administration.

A Chinese nation that was once considered the leader of the Orient was severely weakened by continuous disruptions like the Opium Wars, the Boxer Rebellion and the Sino-Japanese War. Consequently, these events also caused a dent in the nationalist pride and the Chinese people suffered various atrocities during this period.

Naval ambitions

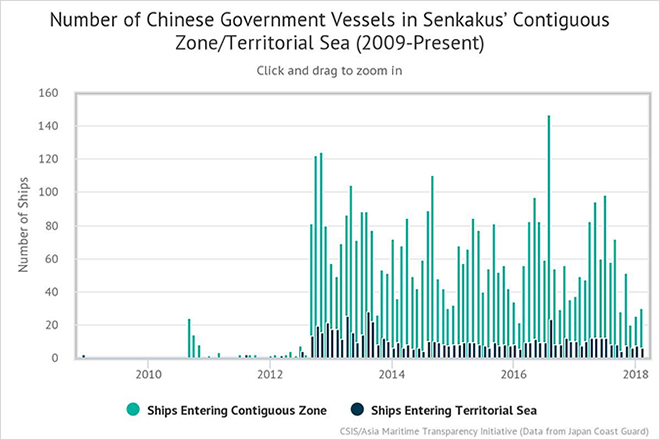

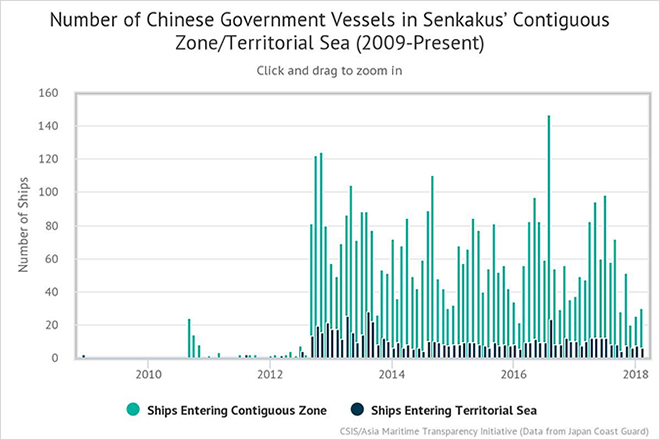

China’s naval capabilities may have come to bear fruits in the present, and the acceleration might have happened in the past few years, but China’s nationalistic ambition to secure a ‘blue water navy’ and to regain its ‘lost territories’ has been a core policy objective of the CPC for some time now. China’s journey to naval power has been paved by successive administrations that have repeatedly harped on the ‘aggrieved power’ narrative to justify their actions. Chinese nationalists demand the development of a ‘blue water navy’ spearheaded by aircraft carrier groups because it would serve the dual purpose of reuniting Taiwan with the Chinese mainland and defending Chinese sovereignty in the above-mentioned territorial disputes. China’s actions in its near waters — reclaiming islands, imposing unilateral fishing bans, employing its maritime militia to harass other countries’ fishermen, using coast guard vessels for gray zone coercion, all form a part of this nationalistic principle to secure territories that it considers to be its own. China’s claim in the South China Sea outlined by the Nine-Dash Line (NDL), often drummed up by state sponsored outlets, displays this sense of historical entitlement. The NDL formulated by the Kuomintang government in 1947, covers majority of the SCS and it infringes upon the sovereignty and maritime boundaries of multiple South East Asian nations, and China makes these claims in the face of international law and seeks to benefit from economic exploitation of the region’s resources. The East China Sea is another example. Figure 1.3 demonstrates how Chinese presence in the contiguous zone surrounding the Senkaku Islands has increased over the last few years. These forays in the East China Sea seek to establish control over natural gas fields present in the territorial sea surrounding the Senkakus, and actions have unsurprisingly been accompanied feverish anti-Japanese sentiment on the Chinese mainland.

China’s claim in the South China Sea outlined by the Nine-Dash Line (NDL), often drummed up by state sponsored outlets, displays this sense of historical entitlement.

Figure 1.3 — Tracking Chinese Government vessels in Senkakus’ Contiguous Zone. | Source

Figure 1.3 — Tracking Chinese Government vessels in Senkakus’ Contiguous Zone. | Source

Naval nationalism

China fits into

Robert Ross’ definition of naval nationalism as the manifestation of nationalist “prestige strategies” pursued by governments seeking domestic legitimacy. According to Ross, “China’s nationalists seek the prestige and power enjoyed by great powers throughout history, including by dynastic China.” The sudden splurge in China’s naval spending is not something that has developed overnight. China’s increased expenditure on its maritime capabilities is a combination of nationalist sentiment, defensive security strategy and growing economic clout. A core concept of Chinese nationalism — ‘recovery of ‘lost territories’, further justifies this evolving naval acquisition program. Naval power has become the crux of domestic legitimacy and this is well reflected in the intentions of naval planners in Beijing to build a robust navy by 2020 around three aircraft carrier groups. As a growing circle of Chinese netizens regularly attach nationalist sentiments to Chinese naval power, the amplification of construction activities in the

Spratly Islands further underscores this, “

pressure from Chinese society.” A powerful People Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) along with a dominant Chinese Coast Guard (CCG) encapsulates the evolving power of the Chinese nation in the minds of its people. Meanwhile, publicly, China masks its national sentiments by depicting a classic case of security dilemma. It

alludes the buildup in naval forces and militarisation of its reclaimed islands to US Navy’s Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPS) in the South China Sea. This process is repeated by Chinese state agencies, state-controlled media outlets and nationalist netizens, every time the US Navy challenges China’s territorial claims.

The sudden splurge in China’s naval spending is not something that has developed overnight. China’s increased expenditure on its maritime capabilities is a combination of nationalist sentiment, defensive security strategy and growing economic clout.

The

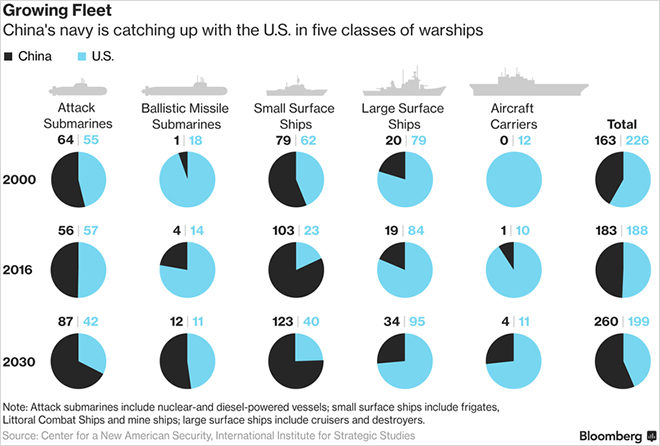

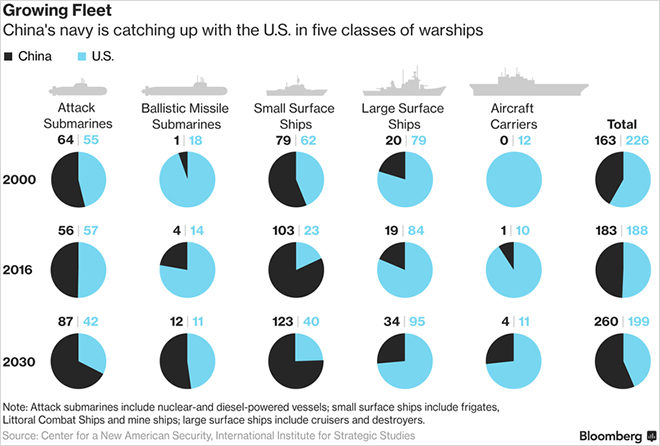

8.1 percent rise in Chinese defense spending this year demonstrates that China’s naval expansion is moving at a steady pace. A majority of this funding will be devoted to finance swift acquisitions and to develop capabilities for anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) operations to deter any ambitious US action beyond the US Navy’s usual Freedom Of Navigation Operations (FONOPs). China has devoted a considerable amount of resources over the past decade to catch-up with US capabilities. The movements of the US Navy dominate Chinese naval strategy, and naval force structures are designed keeping US force deployments in the Western Pacific in mind. The construction of Surface to Air Missiles (SAM) sites and runways on reclaimed islands convert them into actual bases from where Chinese forces can be deployed. The declaration of an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) over these disputed territories further consolidates the position. All this ties into China’s strategy to secure the first island chain of the Western Pacific to extend its national power. Figure 1.4 shows the growth in the number of Chinese warships and what it aims to achieve in the near future. The shrinking gap between Chinese and American conventional naval forces confirms Chinese naval nationalism. Moreover, increased force deployments in the Indian Ocean suggests the presence of a larger strategy beyond China’s immediate littorals. Anti-piracy task force deployments in the Gulf of Aden, submarine patrols in the Indian Ocean and offshore naval bases as far as Eastern Africa, all add to the rising profile of Chinese naval power as China expands its horizon to the high seas.

Figure 1.4 — Growth in Chinese naval capabilities in comparison to US naval forces. | Source

Figure 1.4 — Growth in Chinese naval capabilities in comparison to US naval forces. | Source

Conclusion

China under President Xi has shed its ‘Brand China’ image and shown its true ambitions to the world. Every great power has secured its status on the geo-political stage by using a robust naval force, and China is no different. When national ambitions are frequently stirred by the state administration for popular support, the result is a civil society gripped with fervent nationalism. This in turn influences policy decisions of the state. The key difference in Chinese ambitions is its sense of privilege in the region and its rhetorical duplicity that seeks support, sometimes coercively with initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and a binding Code of Conduct, even as Beijing transgresses their exclusive economic zones (EEZs). In the quest to rejuvenate its great power status, it has injected every section of its naval force — the navy, the coast guard and the maritime militia with considerable autonomy that heeds no one, not even international law. When these forces harass fishermen from other nations and restrict their access to traditional fishing areas, it also antagonises the population of these states and feeds their nationalist sentiments. These actions put to doubt the sovereignty of neighbouring nations, their capabilities and their access to resources, threatening the saliency of norms that have dominated Asian political discourse since the end of the Cold War. Chinese naval power and state prestige go hand in hand, in creating a new security dynamic in Eastern Asia and beyond. Nations have employed a variety of strategies ranging from bandwagoning to balancing to hedging, to deal with an increasingly bellicose China, and are still wrestling with the idea of a Chinese hierarchy in the region. The Chinese state has realised its national prestige by setting the agenda in East Asia, but needs to be cautious that this quest for naval power does not actualise a naval alliance against them.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This is the forty ninth part in the series The China Chronicles.

Read all the articles

This is the forty ninth part in the series The China Chronicles.

Read all the articles  Figure 1.1 — Territorial claims between China and other Southeast Asian nations in the South China Sea. |

Figure 1.1 — Territorial claims between China and other Southeast Asian nations in the South China Sea. |  Figure 1.2 — Territorial dispute over the Senkaku islands in the East China Sea. |

Figure 1.2 — Territorial dispute over the Senkaku islands in the East China Sea. |  Figure 1.3 — Tracking Chinese Government vessels in Senkakus’ Contiguous Zone. |

Figure 1.3 — Tracking Chinese Government vessels in Senkakus’ Contiguous Zone. |  Figure 1.4 — Growth in Chinese naval capabilities in comparison to US naval forces. |

Figure 1.4 — Growth in Chinese naval capabilities in comparison to US naval forces. |  PREV

PREV