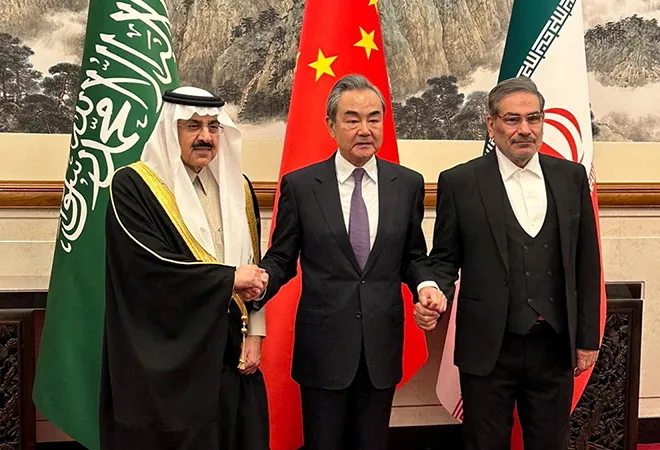

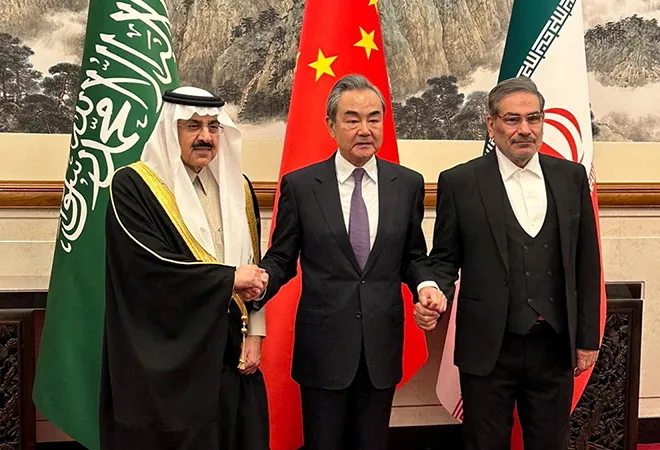

Riyadh and Tehran

agreeing to reopen their embassies after a gap of seven years was not as surprising as the venue from where the news was announced, Beijing. This is a perceptual breakthrough for China, successfully hosting the two geopolitical and ideological poles of power in West Asia (Middle East) and Islam alike. For China, this could be seen as its first major diplomacy victory in the form of a neutral actor outside its immediate interests in the Indo-Pacific. The fact that this deal was announced around the same time as the

20th anniversary of the US invasion of Iraq shows the not-so-subtle messaging from Beijing, posturing itself as a power for ‘good’.

Both Riyadh and Tehran have been in dialogue for some time now to resume diplomatic relations. Talks have not only been envisaged in the regional capitals of Iraq and Oman but even

as far as Brazil. In January 2022, Iranian diplomats

returned to Saudi Arabia to take up their posts in the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) in Jeddah—a strong signal that both parties were showing serious intent to resume diplomatic ties for the first time

since 2016. Iraq, which was increasingly at risk of becoming a proxy battle zone much like Yemen between the Sunni and Shia seats of power, consistently pressed for dialogue even at times when the process was close to collapsing.

Iranian diplomats returned to Saudi Arabia to take up their posts in the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) in Jeddah—a strong signal that both parties were showing serious intent to resume diplomatic ties for the first time since 2016.

China has been gnawing and making its space in the Middle East for some time now, taking advantage of fissures between traditional security partners Saudi Arabia and the US amidst other challenges. While Beijing and Tehran signed an expansive yet rickety 25-year strategic deal in 2021, it also operationalised a significant outreach with the Arab world keeping its energy security as the fulcrum of these engagements. While much of the world concentrated on China’s military aspirations, viewed through the lens of its, for now,

limited military presence near the fringes of the geographic Middle East in places such as Djibouti, it was also preparing to use its position as the second largest economy in the world to good effect. In fact, it was not just those in the Arab world or Iran that were interested, the closest ally of the US in the region, Israel, also found the

lure of the Chinese economy and its advanced technologies irresistible. This waltz with Beijing, of course, was

short-lived.

The fundamental geopolitical and geostrategic anchoring of the US in the region was based on providing security to the likes of Riyadh in exchange for a level of unparalleled energy security. This arrangement,

cemented in 1945 between then US President Franklin D Roosevelt and then Saudi monarch King Abdul Aziz Ibn Saud on board the USS Quincy in the critically important Suez Canal waterway anchored relations between the two up until 2019, when things changed. A mute response from the US under the leadership of President Donald Trump to attacks by

Iran-backed Houthi rebels against Saudi oil installations revved up strategic thinking in the Kingdom, now under the rule of young Crown Prince and heir-apparent Mohammed bin Salman (MbS), who did not take the American absence kindly. With plans to modernise the Saudi economy and shift it away from its addiction to petro-dollars, a more freewheeling economic outreach has been initiated by the Saudis, and for the same, China is an obvious destination. Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Saudi Arabia in December 2022 to

attend the first China–Arab States summit and China–GCC summit was a pivotal moment for Beijing’s economic positioning, which this week, has also translated to a political one.

The fundamental geopolitical and geostrategic anchoring of the US in the region was based on providing security to the likes of Riyadh in exchange for a level of unparalleled energy security.

However, all is not as simple as it may seem, both for China and Saudi Arabia alike. Despite the diplomatic thaw, which still has two-months to be implemented (a long time in the geopolitics of the Middle East), the core issueof a nuclear Iran remains palpable. Despite China’s role here, and it gaining a victory for its image in the region and beyond, Beijing seems both unable to and unwilling to enter regional disputes beyond

mediation and diplomatic manoeuvring, much of which is aimed at its own economic and energy security. This is coupled with the reality that Iran walking back on its nuclear programme remains unlikely. While Tehran may ultimately find a middle path with the West by giving more space to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to have oversight over its facilities, the P5+1 itself may act in a completely different mode post the Ukraine war as West’s relations with

Russia, China, and Iran fracture simultaneously. Beyond the nuclear issue, Tehran, a quintessential

survivalist state, continues to maintain a robust ecosystem of proxies in Syria and Lebanon, giving it access to border regions of both Saudi Arabia and Israel. As murmurs spread over ‘good news’ on the Yemen front coming as well, bringing a terrible war to some sort of closure, the issues between Riyadh and Tehran go both deeper and

further away from the confines of the Gulf geography.

The story for the US in the region might only just be beginning once again, as it is certain that they had a deep knowledge of what was unfolding. US President Joe Biden may have called Saudi Arabia a “

pariah” during his presidential campaign, but his

grudging visit to the country in August 2022 showed that it is easier said than done to decouple from long-standing strategic engagements which, at the end of the day, severely dents American standing as a steadfast partner and ally across the board. This is a perception that the US continues to struggle with post a

botched deal with the Taliban and a subsequent chaotic exit from Afghanistan. At the end of the day, even MbS arguably knows that the security guarantees sought by the Saudis may only have one partner with the capacity, capability, technology, and intent to deliver, that being the US. Allowing Beijing to play mediator, and by association hedging interests, may in fact become a well-timed ploy to pull the US back into the Middle East, mobilising on an increasingly vocal anti-China chamber in Washington DC. While Riyadh would push to maintain a level of strategic autonomy, the US in exchange may well have to shed an absolutist view of ‘us vs them’ when it comes to other actors such as Russia (with whom Riyadh has constructed

OPEC+) and China. Unlike the past 78 years of US–Saudi bonhomie, today the Saudis are asking for equity of interests, instead of outright subjugation in exchange for security.

As murmurs spread over ‘good news’ on the Yemen front coming as well, bringing a terrible war to some sort of closure, the issues between Riyadh and Tehran go both deeper and further away from the confines of the Gulf geography.

Finally, countries such as India should take serious note of these developments. China’s decision-making is becoming bolder on two notable fronts. First, the simple fact that it is a US $18-trillion economy and now approaches the global order in accordance with its economic requirements to not only maintain but sustain and nurture power. Second, it has a clear view of an upcoming ‘big power competition’ with the US and will be more aggressive to be an alternative in areas of traditional Western influence where power vacuums may arise. At the end of the day, China managed to employ the immense pressure Western sanctions had created against Iran while Washington was either unwilling or unable to come up with an offer to Riyadh that would undercut Beijing.

For now, the announcement made in Beijing will have to be implemented over the next 60-odd days as China looks to host an

unprecedented summit between Arab monarchs and Iranian leadership this summer. The success or failure of this may not become a watershed moment for Saudi Arabia or Iran but could well be one for China.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Riyadh and Tehran

Riyadh and Tehran  PREV

PREV