Rejection usually has a negative connotation. When 62 percent of Chileans voted to reject the draft constitution on 4 September in a national plebiscite (with a massive 85 percent turnout), many analysts criticised the constitutional convention as an overtly leftist and ‘woke’ draft. Others lamented that Chile has lost two years convening and compiling a draft only for it to be overwhelmingly rejected.

Yet, in this particular case, we should not be despondent. Chile is undergoing a period of profound socio-political transformation that is larger than the current plebiscite. This is a vital phase of what could be seen as “Chile’s peaceful revolution.”<1>

Though the popular Chilean protests in 2019 did turn violent, it has been followed by a period of constant debate, reconciliation, and most importantly, inclusive, democratic processes like the plebiscites in October 2020<2> and September 2022. Despite the clear rejection, this vote is a sign of maturity that is rare in today’s democracies. Chileans still remain united in the search for a new constitution through a democratic and peaceful process.

The draft constitution had numerous flaws—it was too long, professed broad, nearly utopian ideals without offering a blueprint on how these can be achieved, and attempted far-reaching reforms that deserve more debate before being enshrined in a constitution.

Rather than see the rejection as a failure of the current government led by the 36-year-old Gabriel Boric and the constitutional convention, a more apt comparison may be one made by Gabriel Guerra, a Mexican columnist. Guerra compares the current Chilean administration to Icarus from Greek mythology, who famously flew too close to the sun and perished, with one crucial distinction—in this case, the dispensation’s wings have been burnt, but not melted. They will now have to put in the hard work to rebuild consensus with actors from across the political spectrum and accommodate different views.

Why did Chileans reject the draft constitution?

The draft constitution had numerous flaws—it was too long, professed broad, nearly utopian ideals without offering a blueprint on how these can be achieved, and attempted far-reaching reforms that deserve more debate before being enshrined in a constitution. It had its merits too: it gave women a more equal standing in society, envisioned a far more equitable Chile in terms of access to basic healthcare, education and food, and also paved the way for a more environmentally sustainable country prepared to combat the risks of climate change.

Besides the actual content of the draft, one would be remiss to ignore the role of the media and disinformation in any political process in today’s hyperconnected, digital world. Chile’s more conservative elite poured millions into the ‘reject’ campaign—as much as three times the money spent on social and traditional media by the ‘approve’ campaign. This also led to massive disinformation in support of the ‘reject’ vote, with Reuters confirming that 65 percent of poll respondents encountered disinformation related to the draft constitution; some of the fake news included “false information that the new constitution would allow abortions up to the ninth month of pregnancy and would abolish private property.” Marta Lagos, Founder of Latinobarómetro—the gold standard for polling in Latin America—described the disinformation campaign as follows: “The destruction of ‘truth’, the use of ‘suspicion’, “mistrust” as weapons to attack the deepest ‘hope’ of a people, a campaign without any limits, like Trump’s, where you do everything to win.”

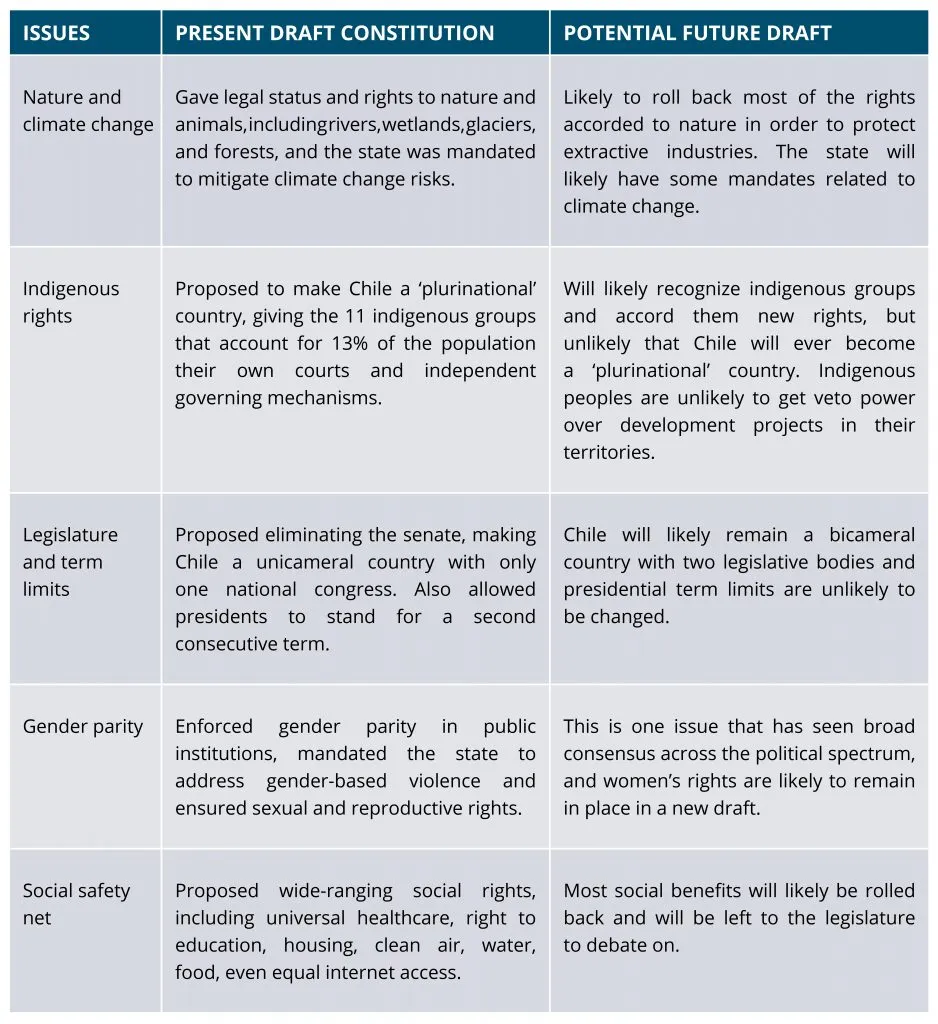

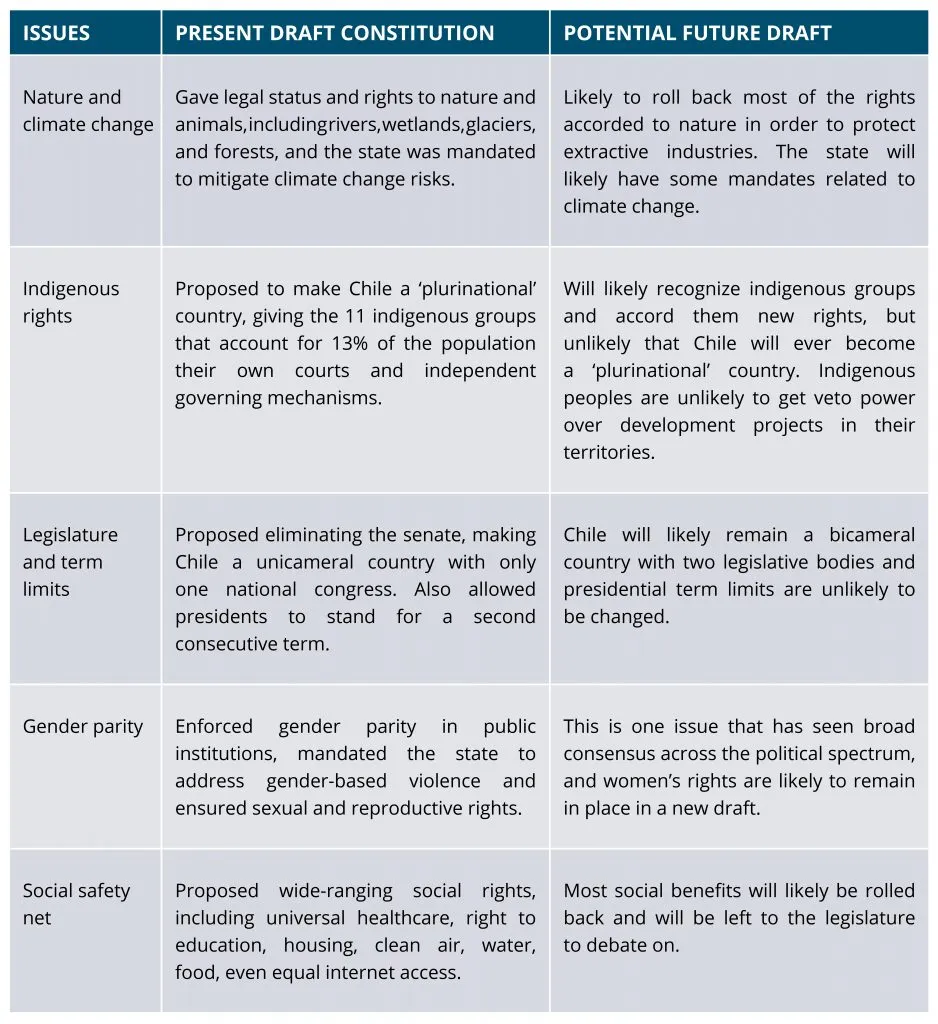

So, what did the draft include, and what shape might a new draft constitution take?

Expectations going forward?

Expectations going forward?

Perhaps the most striking feature of Chile’s ‘peaceful revolution’ is the openness for compromise by the country’s leadership, both in government and civil society. Boric has already reshuffled his cabinet and named more moderate, centrist ministers to manage the interior, health, science, and energy portfolios; he is also open to the election of a new constituent assembly. Boric will likely enact more moderate policies during the remainder of his term.

Despite the resounding rejection of the current draft, most Chileans remain steadfast in their demand for a new constitution, even if it means waiting a few more years until creating one that is more palatable to the majority of the population. The constitution drafting process has already increased awareness of the need for more equal rights for women and better management of Chile’s environment and its natural resources. As the Financial Times’ Michael Stott notes, Chileans will likely form a new charter “that gives stronger individual rights to Chileans and a bigger role to the state in guaranteeing essential public services. In short, something more like a European-style welfare state and less like a Friedmanite free market.”

Despite the resounding rejection of the current draft, most Chileans remain steadfast in their demand for a new constitution, even if it means waiting a few more years until creating one that is more palatable to the majority of the population.

It may also be useful to remember that constitutions are, after all, foundational documents, akin to the North Star that guides voyagers. Constitutions are meant to support democratic institutions and processes, not supersede them. Legislatures, the courts and the executive head of government will continue to play an arguably more important role as constant arbiters of social justice.

Chile is also not the only country to go through this constitutional process in recent years and can learn from others on a similar path. Naomi Roht-Arriaza, a distinguished professor of law emeritus at the University of California, Hastings, reaffirms that “Chile should learn from Tunisia, another country that attempted broad, inclusive constitutional reform after widespread protests. As several analysts told me, it would have been better for Tunisians to aim for less sweeping reforms at the constitutional level and spend more time on ordinary legislation that directly responded to the widespread protests of 2011. The same may be true of Chile.”

<1> Not to be confused with Germany’s ‘peaceful revolution,’ which saw the reunification of East and West Germany in 1990.

<2> Nearly 80 percent of Chileans voted in 2020 to replace the current version of the constitution that was imposed on the country by then-president Gen. Augusto Pinochet.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV