This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

According to the

World Inequality Report 2022 (WIR 2022), India and Brazil are countries with ‘extreme’ inequality amongst low- and middle-income group countries. China is slightly better as it is characterised by only ‘high levels’ of inequality. India is also amongst countries that experienced ‘spectacular’ increase in inequality along with USA and Russia. Amongst countries in South and Southeast Asia, the ratio of the income of the top 10 percent to the bottom 50 percent is

22 for India which is much higher than 17 for Thailand, a military dictatorship. Globally, the entire drop in growth in the share of income going to the

bottom 50 percent of the population due to COVID-19 in 2020 was because of South and Southeast Asia, particularly India. When India was removed from the data set, the share of income going to the bottom 50 percent was found to increase slightly in 2020.

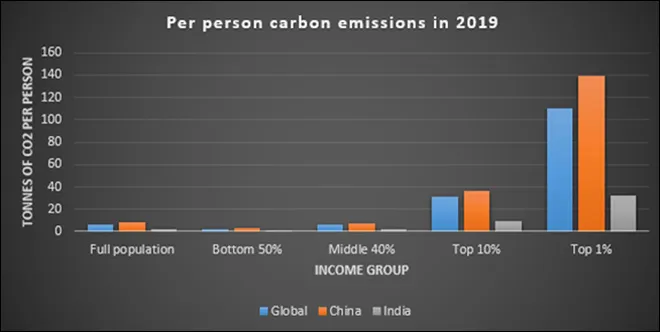

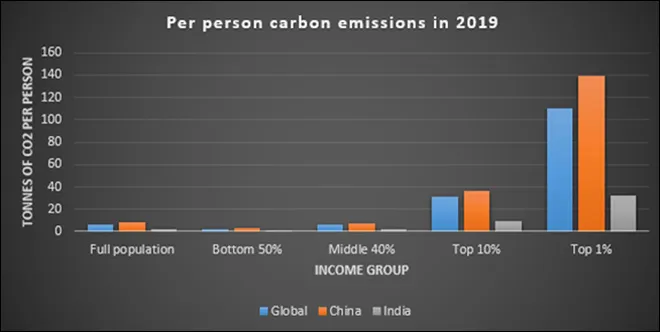

Carbon Inequality

The inequality in income and wealth naturally translates into carbon inequality that arises from differences in consumption. Within India, the national average per person emission was

about 2.2 tonnes of carbon dioxide (tCO

2). The middle 40 percent emitted about

2 tCO2 per person, the bottom 50 percent about 1 tCO

2 and the top 10 percent about

8.8 tCO2 per person in 2019. This pattern is not unique to India.

Amongst countries in South and Southeast Asia, the ratio of the income of the top 10 percent to the bottom 50 percent is 22 for India which is much higher than 17 for Thailand, a military dictatorship.

Globally, on average each individual emitted just over

6.5 tCO2 in 2021. In 2019, the bottom 50 percent of the world population emitted only

1.6 tCO2 per person accounting for 12 percent of emissions while the middle 40 percent emitted 6.6 tCO

2 per person accounting for about

40 percent of total emissions. The top 10 percent emitting

31 tCO2 per person accounted for 47.6 of total emissions and the top 1 percent or about

77.1 million people emitting 110 tCO2 accounted for 16.8 percent of emissions. The top 0.1 percent or just 7.7 million people emitted

467 tCO2 per person and the top 0.01 percent or just

770,000 people emitted a staggering 2531 tCO

2 per person in 2019.

Carbon inequality: Within and between countries

In multilateral climate negotiating platforms, India has

consistently upheld the principle of equity between countries. Just before COP 26, the

Government of India welcomed the launch of

climate equity monitor (CEM), an online dashboard for assessing, at the international level, equity in climate action, inequalities in emissions, energy and resource consumption across the world. According to

the CEM, its objective is to counter messages from western sources that rely on or promote methodologies that pay no more than scarce attention to equity, differentiation, and historical responsibility, all guiding principles of the UNFCCC (United Nations framework convention on climate change). The

CEM observes that even where the discourse claims to focus on equity, it privileges views from the Global North that seek to establish themselves as acting on behalf of the rest of the world. The

CEM aims to address this disparity and promote a new narrative where the South looks out for the North and the rest of the world. As nations rather than individuals are the units of negotiation in multilateral climate negotiations, contesting ‘between country’ inequality is a perfectly legitimate position for India. However, this does not mean ‘within country’ inequalities can be ignored.

According to

WIR 2022, in 1990, 63 percent of the global carbon inequality was due to ‘between country’ inequality but in 2019, 63 percent of global carbon inequality was due to ‘within country’ inequality. Looking within to address carbon inequalities will strengthen India’s case for addressing between country carbon inequality in multilateral platforms.

Most of the emission reduction in India to meet the targets of the Paris Agreement must come from the

top 10 percent of India’s population whose emissions are higher than world average emissions. Compared to 2019 levels, Indian emissions can increase by 70 percent or by

1.5 tCO2 per person until 2030. Emissions of the bottom 50 percent can increase by 281 percent to 2.7 tCO

2 per person by 2030 while emissions of the middle

40 percent can increase by 83 percent to 1.7 tCO

2 per person. However, emissions of the top 10 percent must fall by

58 percent to 5.1 tCO

2 per person to meet the targets of the Paris Agreement.

Just before COP 26, the Government of India welcomed the launch of climate equity monitor (CEM), an online dashboard for assessing, at the international level, equity in climate action, inequalities in emissions, energy and resource consumption across the world.

Climate policies recommended by

WIR 2022 that target the bottom 50 and the middle 40 percent of the population include public investment in renewable energy supply, protection for those affected by the transition to cleaner energy sources, construction of zero carbon social housing, cash transfer for increase in fossil fuel energy prices. Policies that target the top 10 percent include wealth or corporate taxes with pollution top-up.

The suggestion of a global carbon incentive (GCI) to address carbon inequality from

Raghuram Rajan, former Governor of the Reserve Bank of India to address global carbon inequality is also a credible option. Under GCI, every country that emits more than the global average of around

5 tCO2 per person would pay annually an amount calculated by multiplying the excess emissions per person by the population and the GCI into a global GCI fund. Countries below the global per person average would receive a commensurate pay-out. With a per person emission way below the cut-off of 5 tCO2, India would not pay anything but instead receive a pay-out from richer countries. If the initial GCI is set at

US$ 10/tCO2 emissions above the global average, substantial sums can be raised to address carbon inequality.

If the idea of a GCI is applied to address ‘within country’ carbon inequality in India, the top 10 percent or 138 million people will have to pay-out a total of over US$5.2 billion annually. This is about a third what the

government spends on climate change each year. Compared to the current carbon price of close to

€80/tCO2 at the EU ETS (European union emission trading system) in December 2021, the GCI of US$10/tCO

2 is very low but it is a good starting point. The key bureaucratic challenge would be to identify the top 10 percent of carbon emitters, but it is not impossible.

Is Inequality Fair?

India’s current climate policies overwhelmingly

promote production of cleaner sources of energy or technologies through large financial and other incentives to the private sector that includes protection from external competition (through

import duties and tax breaks for example) at one end and a guaranteed market (through various

mandates to increase the share of clean energy) at the other. The beneficiaries, primarily the promoters and shareholders of private entities constitute a large part of the top 10 percent of emitters.

Empirical studies show that near-term climate action such as policies that incentivise production of clean energy comes at some cost to the poor. Using the nested inequalities climate economy (NICE) model, the study shows that an equal per person refund of carbon tax (or equivalent such as the GCI) revenues can pay large and immediate dividends for improving well-being, reducing inequality, and alleviating poverty.

It is unlikely that policies that favour the bottom of the carbon pyramid will find favour in India where power is characterised by the bond between capital and state. As noted by Nobel laureates Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee in the

foreword of the WIR 2022, inequality is not seen as a problem under private sector-led growth that celebrates the unabashed accumulation of individual wealth. The fact that the

top marginal income tax rate in India has declined from a peak in the 1970s to a level that is lower than the top marginal income tax rate in much richer countries including Japan, United Kingdom, Germany, France, and even the USA illustrates state preference for capital.

Using the nested inequalities climate economy (NICE) model, the study shows that an equal per person refund of carbon tax (or equivalent such as the GCI) revenues can pay large and immediate dividends for improving well-being, reducing inequality, and alleviating poverty.

The conclusions of an academic study on this subject that found that humans, even as young children and babies, actually prefer living in a world in which

inequality exists is relevant in this context. It sounds counter-intuitive, but the study showed that when people find themselves in a situation where everyone is equal, many become bitter as those who work hard are not rewarded, and slackers are over-rewarded. This makes inequality ‘fair’ when those in the top 10 percent are framed as hard workers and those below as slackers. But climate change, like the pandemic, is a problem that does not respect borders or man-made barriers and labels. Policies that favour the top 10 percent may be ineffective in saving them when the bottom 90 percent crumbles under the weight of climate change.

Source: World Inequality Report 2022

Source: World Inequality Report 2022

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV