The World Health Organisation (WHO) has identified

climate change as the ‘single biggest health threat facing humanity’. It notes that climate change directly affects the

environmental and social determinants of health, and is likely to cause 250,000 additional deaths per year from malnutrition, malaria, diarrhoea, and heat stress during the period 2030–2050.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has identified climate change as the ‘single biggest health threat facing humanity’.

Developing countries of the Global South will be amongst the most vulnerable to health risks linked to climate; and an Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)

report of 2022 has observed that in Asia, climate hazards are contributing to a wide range of adverse health outcomes and a higher incidence of diseases.

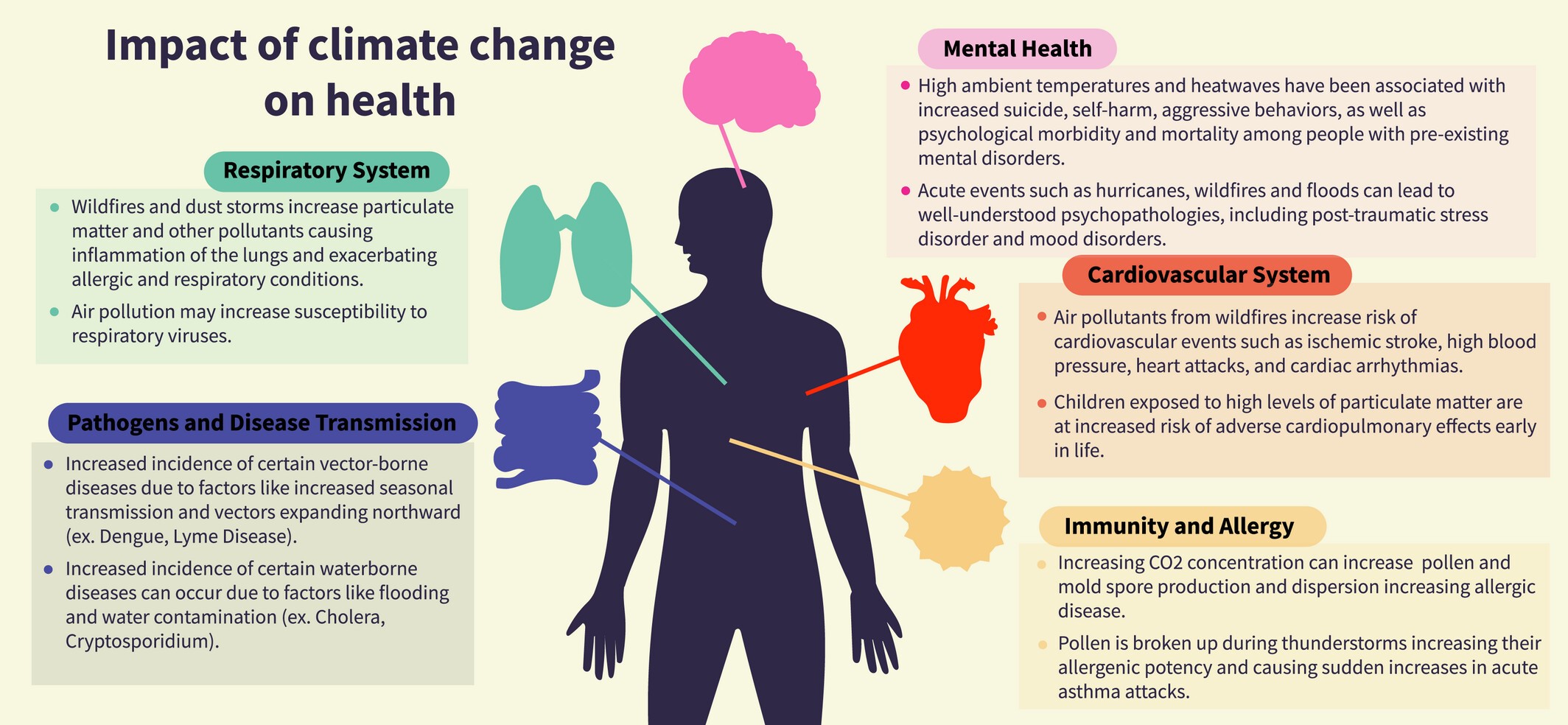

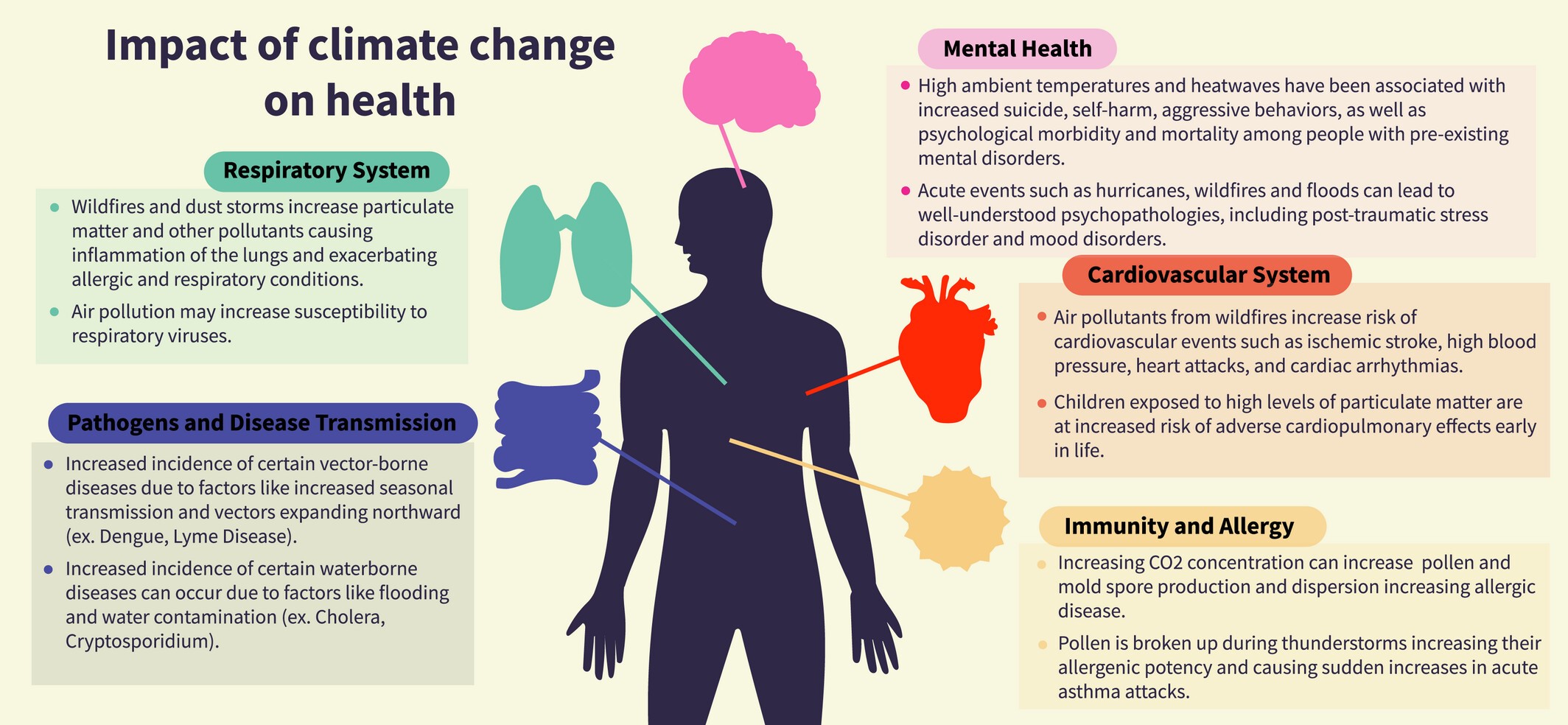

Figure 1

Figure 1

The climate–health nexus in India

India is highly susceptible to climate-related health risks, and climate change is affecting health across the country in three principal ways:

- Climate change and variability directly impact personal health

- Food security is affected, with negative implications for nutrition levels

- Extreme weather events resulting from climate change disrupt healthcare services

Extreme heat and its consequences for health

Our summers are growing longer and hotter, note

reports from the India Meteorological Department. Parts of India experienced their

hottest summers ever in 2016, 2021, and 2022; and, in 2023, a

heatwave alert was broadcast for western India as early as February. Heatwaves are fast gaining in frequency, and the number of Indian states affected by them since 2015 had more than

doubled by 2020.

Heatwaves are not simply

exacerbating respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, illnesses such as heat exhaustion and heatstroke, and conditions such as dehydration are also becoming increasingly widespread, particularly amongst children and the elderly. The enervating effects of heat on the poor and outdoor workers can be hazardous, and sometimes lethal. The manner in which extreme heat saps health and vitality affects economic productivity as well. By 2050, half of the afternoon work hours across various categories of work in India are likely to be lost because of the need for rest breaks.

Heatwaves are fast gaining in frequency, and the number of Indian states affected by them since 2015 had more than doubled by 2020.

Moreover, intense heat and stagnant air increase the amount of ozone pollution and particulate matter; and in keeping with worldwide trends, in India too, the number of annual days of

extreme heat and extreme air pollution is increasing. By

2050, the frequency of these twin phenomena is projected to increase exponentially, and when combined with

other contributors to air pollution, a sharp rise in the incidence of diseases, cognitive and neurological impairments, and harmful effects on expectant mothers and infants is expected.

Finally, a hotter climate, erratic and variable rainfall, and drought-like conditions across parts of India have also led to a

surge in vector-borne diseases (VBDs). VBDs such as the Nipah virus, the Zika virus, chikungunya, and dengue have exhibited signs of becoming

endemic.

Diarrheal diseases are also regarded as a key climate-induced health challenge, and according to the National Family Health Survey, the prevalence of childhood diarrhoea in India increased from 9 percent to 9.2 percent between 2016 and 2020. Diarrhoea is today the country’s

third most common disease responsible for under-five mortality.

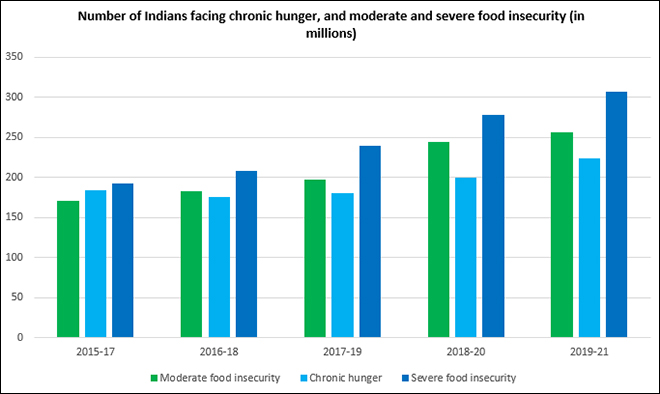

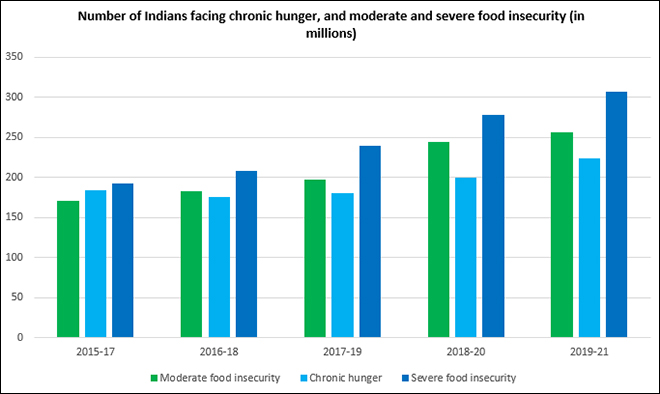

Food insecurity and falling nutrition levels

Several studies have shown that the changing climate and resulting natural calamities are causing lower agricultural yields and driving down the nutritional value of crops in India, leading to food insecurity and malnutrition on a massive scale. The yield and nutritional content of rice and wheat, for example, has

fallen drastically; and in states like Odisha that are especially prone to recurrent natural disasters, the lack of food security has led to

chronic long-term malnutrition among children.

Figure 2

Figure 2

Disruptions to health systems and services

There have been numerous occasions where extreme weather events in India have destabilised and disrupted health systems and services. In 2020, for instance, super-cyclone Amphan ravaged large swathes of Odisha and West Bengal, bringing COVID-19 relief efforts and hospital services to a grinding halt. A fortnight later, cyclone Nisarga tore into Maharashtra, wreaking

havoc on medical services while the state grappled with the highest number of COVID cases in India. Two years later, devastating floods in Assam paralysed health services across multiple districts, and a cancer hospital in waterlogged

Cachar found itself treating patients on an open road.

Adaptive policies and responses

A number of Indian policies and plans recognise climate’s impact on health, but their implementation does not always focus sufficiently on building climate-resilient health systems. For instance, the

National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC) broadly recognises that climate change could affect the health of specific demographic groups, and accelerate the spread of VBDs to newer regions. The Plan, however, merely recommends conducting further research into disease patterns and causes. A stronger focus on

action points such as boosting ‘the provision of primary, secondary, and tertiary health care facilities’ and improving ‘public health measures, including vector control, sanitation, and clean drinking water supply’ could be immensely valuable.

A fortnight later, cyclone Nisarga tore into Maharashtra, wreaking havoc on medical services while the state grappled with the highest number of COVID cases in India.

At present, the NAPCC’s eight National Missions do not include one on health. It is imperative, therefore, that the draft

National Action Plan for Climate Change and Human Health, tabled for approval in 2018, be finalised and deployed. For the time being, this lacuna is being addressed—to some extent—by the

National Programme on Climate Change and Human Health, which seeks to mitigate the health impacts of climate change, and is sensitising stakeholders, forging cross-sectoral collaborations, strengthening health preparedness, and building the capacities of healthcare systems in this regard.

Another significant policy text is the updated

National Disaster Management Plan (NDMP) of 2019, which takes a comprehensive and well-structured approach to addressing the intersection of climate and health challenges. Based on the belief that preventing disasters or reducing risks can lead to favourable health results, the NDMP offers a

framework for states to enhance the robustness of healthcare systems, strengthen communities' ability to handle and recover from disaster effects, incorporate risk reduction strategies into all tiers of healthcare, and consistently engage health experts and emergency managers in the planning stages before a climate event occurs.

Strategic partnerships with the media could help heighten public consciousness about how health might be defended against climate hazards.

The success of the NAPCC and NDMP will eventually depend on how well states adapt and execute them via their State Action Plans on Climate Change (SAPCCs) and State Disaster Management Plans (SDMPs). Until now, addressing health risks related to climate change has not always been accorded due priority when implementing interventions at the state level. It is crucial to urgently decentralise the implementation of these plans as much as possible, working together with stakeholders at the state, district, Panchayat, and community levels. Additionally, there is a need to raise awareness and involve healthcare personnel at all levels.

The knowledge and insights of health and climate actors should be recorded to develop best practices related to climate adaptation. India already possesses various

compendia of this kind, but there is a demand for more examples or case studies of how the health sector can effectively withstand climate risks, which can then be showcased as models for emulation elsewhere. In parallel, it is important to create online platforms that facilitate the sharing of this knowledge. Furthermore, strategic partnerships with the media could help heighten public consciousness about how health might be defended against climate hazards.

The training of healthcare professionals, including ASHAs, should incorporate evolving climate-related risks and requirements.

Ultimately, three key

structural changes should be initiated. First, health systems must be optimised and oriented towards effectively tackling the distinct challenges of the climatic zone in which they function. This requires tailoring local health infrastructure, services, and capacities accordingly. Second, the training of healthcare professionals, including ASHAs, should incorporate evolving climate-related risks and requirements. There is, thus, an urgent need to establish programmes for enhancing skills. Also, teams of healthcare workers trained to manage health crises related to climate changes could be stationed in areas that are particularly prone to disasters. Finally, to ensure a harmonious integration of climate initiatives and advancements in healthcare, various ministries and governmental departments should jointly devise strategies, establish shared goals, and include inputs from non-governmental stakeholders in their planning and execution processes.

Anirban Sarma is a Senior Fellow at Observer Research Foundation

Mridula Ramesh,

The Climate Solution: India’s Climate Change Crisis and What We Can Do about It (New Delhi: Hachette, 2018), 60–61.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has identified

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has identified

PREV

PREV