In recent months Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka have faced power outages which at times have lasted 10-14 hours a day. In the face of energy shortages, the cost of electricity generation in these countries has also spiked dramatically. Such “load-shedding” and rising costs have adversely impacted the economies of these three nations which have all witnessed a drop in their forex reserves to record lows. This article analyses the widespread energy insecurity in these South Asian nations and argues that while unforeseen global factors have a major hand to play, domestic power generation policies are also to blame for their predicament.

< style="color: #163449;">High import prices of fossil fuels

At first inspection, the volatility in global energy markets due to the Russia-Ukraine war appears to be the primary cause of power scarcity in South Asia. As Russia has limited its gas exports to Europe, the price of natural gas has skyrocketed on the continent where imports make up 83 percent of the gas consumption. Consequently, the entry of European nations into the global spot market to replace supplies has had ripple effects on the Asian spot market for Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG). Prices of LNG in the Asian market have surged nearly 10 times from average summer rates and many emerging Asian economies are finding it extremely difficult to compete with richer European nations for shipments. With winter approaching, when LNG demands peak globally, prices are predicted to spike even further.

< style="color: #0069a6;">Prices of LNG in the Asian market have surged nearly 10 times from average summer rates and many emerging Asian economies are finding it extremely difficult to compete with richer European nations for shipments.

Soaring prices and dwindling foreign reserves have compelled Pakistani Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif to declare that Islamabad “cannot afford” to purchase LNG at such high prices. A similar trend has been exhibited in Bangladesh where high prices have slowed down gas purchases.

However, it must be noted that such volatility in the LNG market has been a feature even before the war started and should have served as warning signs for South Asia. Since 2019, prices of LNG hit record lows and then record highs in 2021 as the market reacted to pandemic-enforced closures and then a sudden resurgence in global demand, creating supply-demand bottlenecks.

These same events have caused identical uncertainty in oil prices. While supply-demand bottlenecks were driving oil prices up, the disruptions caused by the Ukraine war led to a further spike in prices. The recently announced OPEC+ supply cuts and European Union embargo on Russian crude oil will further lead to a tighter oil market in the near future. High costs have already resulted in the closure of diesel-run power plants in Bangladesh and Pakistan, and power outages in Sri Lanka as its bankrupt economy struggles to muster funds for oil imports.

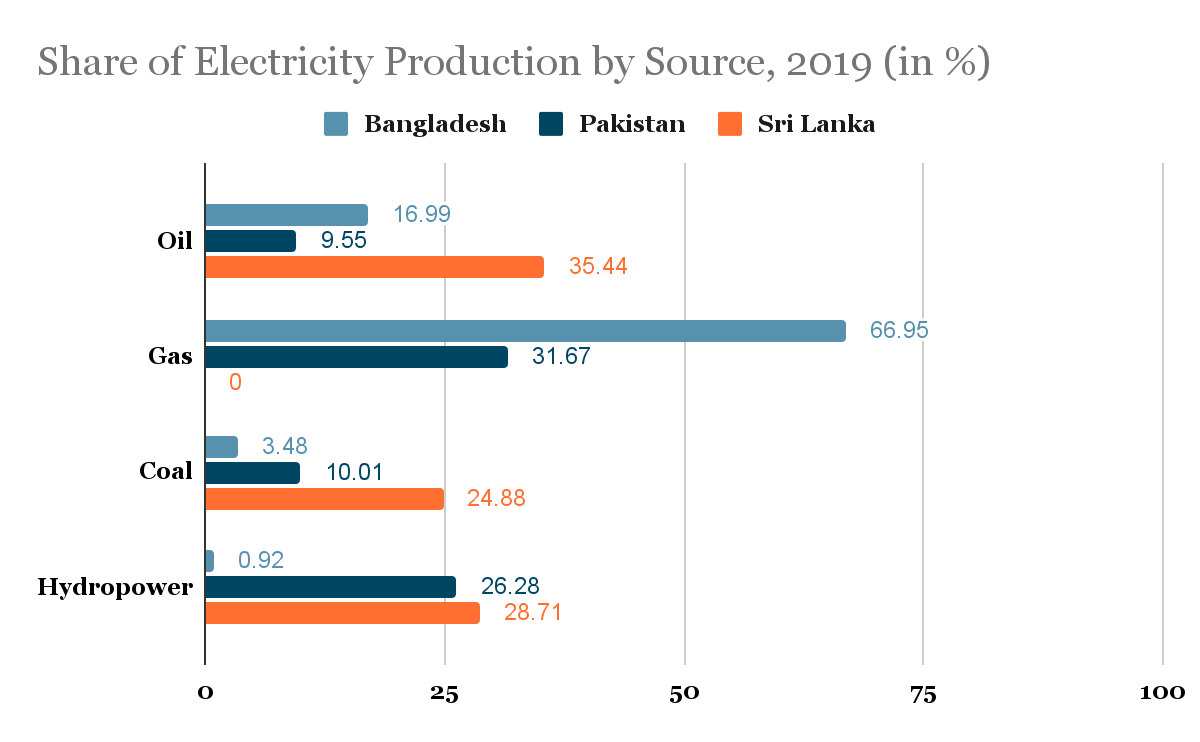

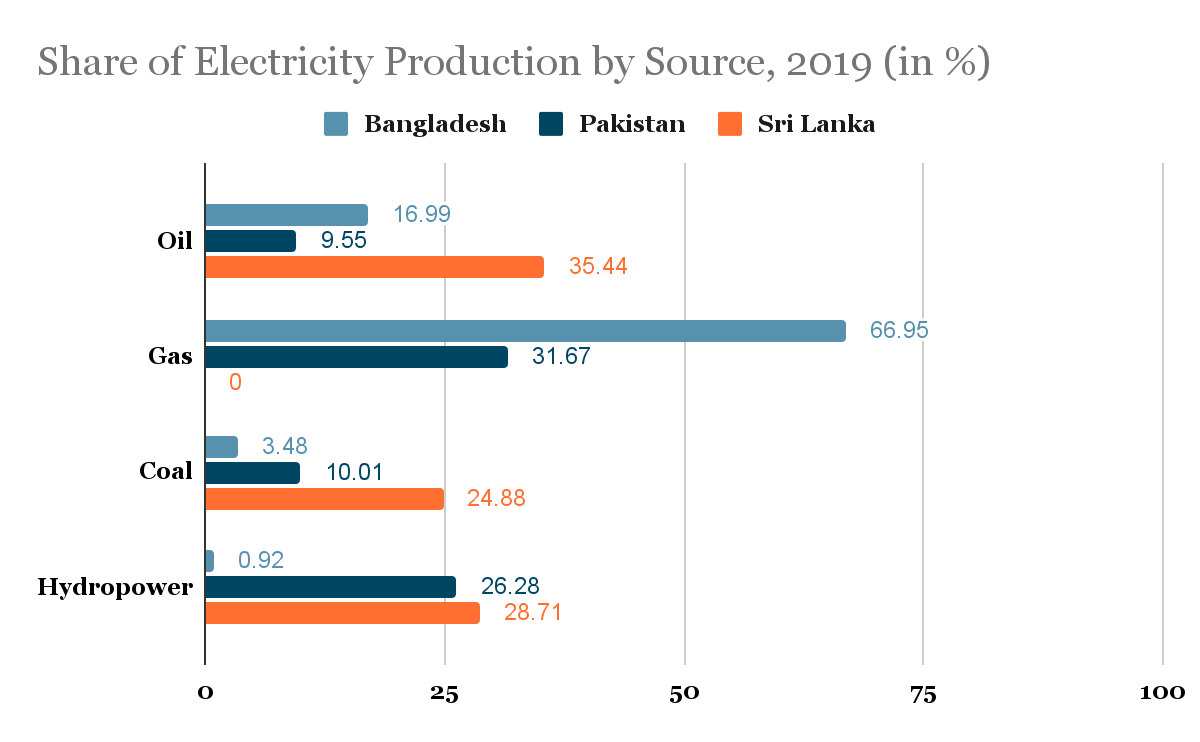

Such volatility in global energy markets is detrimental to the economies of South Asian nations and their ability to produce electricity. The absence of sufficient infrastructure to tap resources of vital fossil fuels such as oil, natural gas, and coal has meant that the supply of resources for electricity generation in these countries is to a great extent met through imports. In recent times, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka have paid a heavy price for their over-reliance on fossil fuels and have seen their import bills surge to unsustainable levels. Thus, even though these countries have sufficient electricity generation capacity, several power plants remain idle due to high costs. The current situation in these nations, although exacerbated by the ripple effects of the Ukraine war, has highlighted how pegging energy security on volatile commodities is a high-risk and costly affair in the long run.

(Note: Data from 2019 was taken to display the electricity mix before the COVID-19 Pandemic and Russia-Ukraine War) Source: Our World in Data Country Profiles

(Note: Data from 2019 was taken to display the electricity mix before the COVID-19 Pandemic and Russia-Ukraine War) Source: Our World in Data Country Profiles

< style="color: #163449;">Shortcomings of Domestic Power Policies

Yet when assessing the current energy woes of these South Asian nations, one must also look at national policy decisions in the electricity sector which have contributed, directly or indirectly to the present situation.

Despite being heavily reliant on natural gas for electricity generation, Pakistan and Bangladesh have continued to import close to half of their LNG supplies from the spot market as opposed to securing long-term contracts with gas providers which are more immune to market shocks. Their LNG import strategies over the past decade had been based on the premise that natural gas would remain abundant and cheap in the foreseeable future. As that prediction has proven false, it has exposed the two nations to the volatility of market prices.

In Bangladesh, the state’s policy to provide capacity payments to independent power providers (IPPs)—a fee paid on the amount of power the plant can generate, even if it remains idle—has proved costly for the Bangladesh Power Development Board (PDB). This has created an issue of over-capacity as power generation capacity has raised to 25,700 MW against a peak demand of 15,000 MW. In the fiscal year 2020-21, capacity payments to the IPPs amounted to 132 billion takas (US$1.40 billion) and an equivalent amount was paid in subsidies to state-owned power utilities. This capital could have been better utilised in building other necessary electricity infrastructure.

< style="color: #0069a6;">The Building Energy Code of Pakistan was developed in 1990 and hasn’t been regularly updated since to keep up with increased demands and new technological innovations.

Pakistan, on the other hand, is infamous for neglecting energy efficiency and conservation measures. While governments have focused on increasing its capacity, demand side reductions through conservation have not been addressed in subsequent national policies. Households consume 50 percent of the total electricity delivered in Pakistan, and yet do not feature in energy conservation policies. The Building Energy Code of Pakistan was developed in 1990 and hasn’t been regularly updated since to keep up with increased demands and new technological innovations. A well-functioning energy efficiency regime in Pakistan could have helped to reduce the present supply-demand gap and contributed to dealing with the power crisis.

Electricity policy in Colombo’s power sector has also displayed shortcomings. Despite having huge potential for renewables like solar and wind, Sri Lanka has shown little conviction in this regard. Even after the announcement of plans to completely transition to renewables by 2050, the three Long Term Generation Expansion Plans (LTGEP) Colombo has issued since continue to feature significant coal projects to be added as late as 2039. The Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB) enjoys a monopoly on power generation in the country and benefits from the dependence on fossil fuels. This highlights how the CEB’s plans continue to contradict the renewable energy policy, and go against the widespread environmental concerns around coal plants expressed by the Sri Lankan public.

This is perhaps a common glaring blind spot of the energy landscape in all three South Asian nations as they have provided a low impetus for renewable projects. Renewable energy forms only a negligible share of Bangladesh’s electricity mix, and while Pakistan and Sri Lanka have a significant presence of hydro-power projects, the susceptibility of these countries to climate events such as droughts and floods have rendered these power plants unreliable. There is a strong need to diversify their renewable energy infrastructure to mitigate insecurity arising from rising costs of fossil fuels, and impacts of adverse climate events on the region’s water cycle.

< style="color: #0069a6;">Renewable energy forms only a negligible share of Bangladesh’s electricity mix, and while Pakistan and Sri Lanka have a significant presence of hydro-power projects, the susceptibility of these countries to climate events such as droughts and floods have rendered these power plants unreliable.

< style="color: #163449;">Conclusion

The present case of Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka has shown that a heavy reliance on imports of volatile commodities proves costlier in the long run. This, when coupled with short-sightedness in domestic power policies and a half-hearted desire to shift to more secure renewables, forms the perfect recipe for disaster in the face of external shocks.

The current crisis has forced these South Asian nations to rethink their future energy landscape and security. Turning to renewables, identifying and redressing shortcomings in domestic power policies, and exploring shared regional electricity grids with like-minded nations are some ways in which these states can reduce their import dependency and ensure greater power security. These measures are of course long-term solutions to their dilemma and require significant investments and reliable partnerships.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV