Biohacking refers to modifying and enhancing human biological systems to elongate or improve the human experience. As advances in biotechnology and genetics have accelerated, individuals and communities participate in this process, motivated by protecting personal medical data and open-source medicine. However, the rapid growth of biohacking has raised significant ethical, social, and regulatory concerns.

Biohacking can also include body modification. Some biohackers enhance their physical appearance or capabilities by implanting electronic devices, magnets, or radio-frequency identification (RFID) chips.

The most known type of biohacking is genetic engineering. The most popular experiments done in this area are by Josiah Zayner, a famous biohacker. While some experiments have been successful, the more complex range of home-based genetic biohacking, like injecting CRISPR DNA or altering cell lengths in a human, have been unsuccessful. A similar field is the consumption of Nootropics, chemical drugs that claim to enhance memory, focus, and creativity.

Biohacking can also include body modification. Some biohackers enhance their physical appearance or capabilities by implanting electronic devices, magnets, or radio-frequency identification (RFID) chips. These enhancements can enable users to interact with technology more seamlessly or gain new sensory experiences, bringing the era of cyborgs called ‘Grinders’ closer.

The existence of biohackers indicates the frustration of the public and professionals over the speed of biotechnology outcomes due to “over-regulation.” However, biohacking itself garners ethical concerns around genetic modification and self-administration of unregulated drugs, the health risks associated with it, and the inequality to access that are enhanced by social and economic backgrounds.

The existence of biohackers indicates the frustration of the public and professionals over the speed of biotechnology outcomes due to “over-regulation.”

Further, genetic biohacking experiments, whether conducted on oneself or others, present significant public health risks. These risks include the potential use of interventions with inadequate safety or efficacy, the absence of genuine informed consent, and the introduction and adoption of unsafe and unproven “treatments” into the market. Leaving genetic biohacking unregulated further amplifies these public health risks, as many experiments utilise easily accessible materials and equipment from companies catering to the do-it-yourself (DIY) market or utilise those that are freely shared among biohackers.

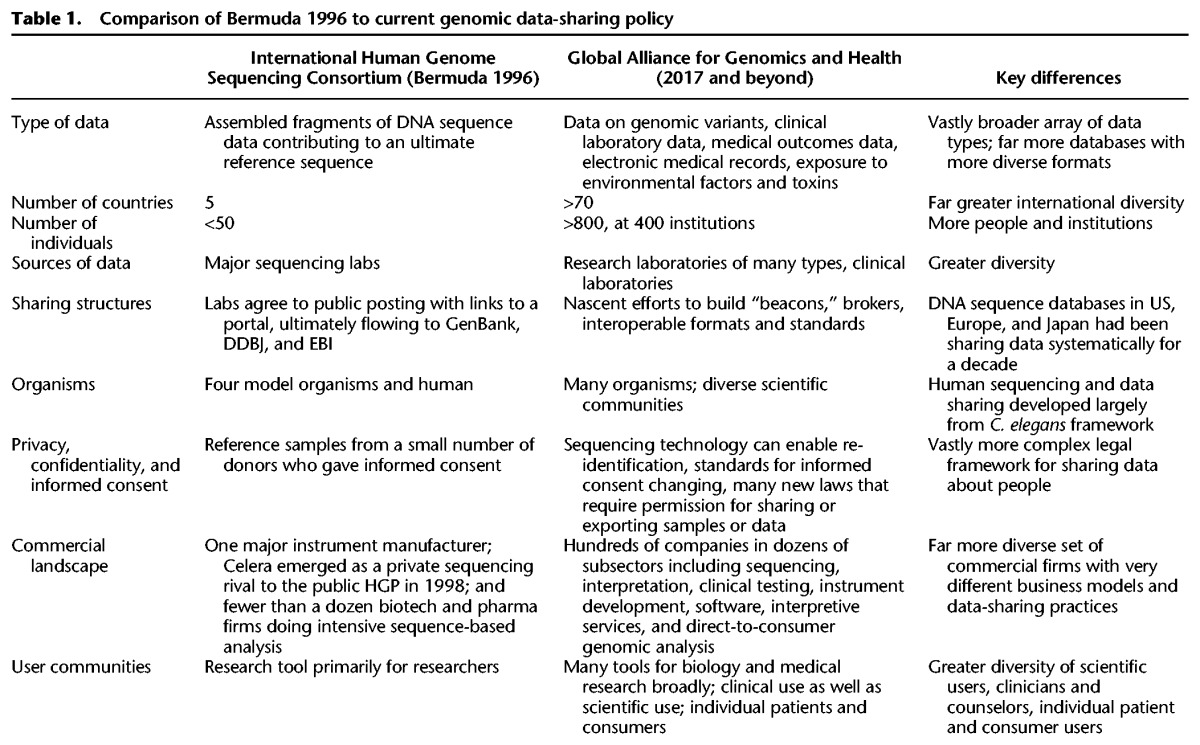

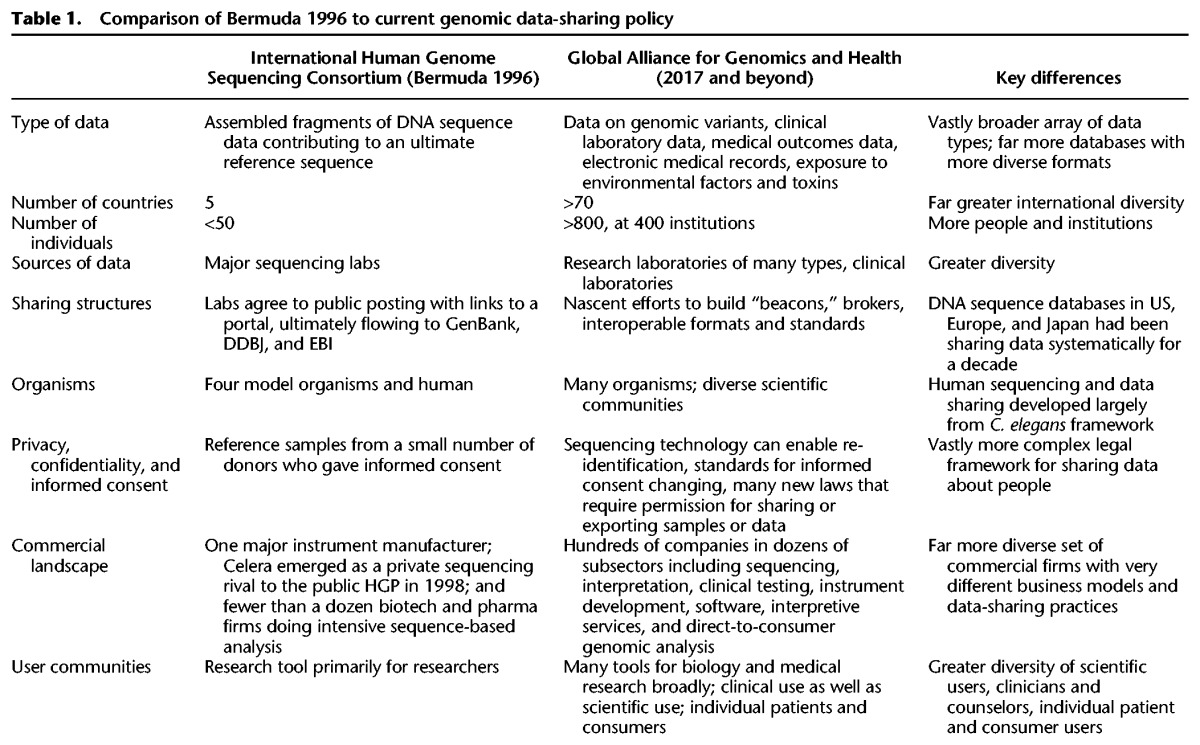

In 1996, five countries, Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom (UK), France and the United States (US), met in Bermuda to sign the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium (Bermuda Principles 1996). In 1999, China joined the agreement.

Source: Cook-Deegan, Robert, and Amy L McGuire, “Moving beyond Bermuda: sharing data to build a medical information commons.

Currently, the Global Alliance for Genomic Health (GA4GH) has over 70 undersigned countries and expands on the scope of the Bermuda Principles. However, neither comprehensively govern informal biohacking globally.

As biohacking depends greatly on biological data, information sharing, and upholding clinical research standards, it becomes imperative for countries to align themselves with global biohacking standards and to ensure that the national state actors enforce such measures.

The regulatory landscape

There have been state efforts to include biohacking in more formal arenas of learning and development. For example, in the US, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) has been actively engaging with the biohacking community since 2009 to ensure safe and secure scientific research and to prevent the potential misuse of biological materials by malicious actors. This outreach, generally welcome by US biohackers, aims to build rapport with biohackers and foster a deeper understanding of their work and technologies. The FBI’s Biological Countermeasures Unit has studied the risks posed by biohacking concerning bioterrorism and has fostered strong relationships with community labs where genetic experimentation occurs.

However, some European biohackers approach this engagement with scepticism and caution, stemming from historical encounters with law enforcement intrusions. They are apprehensive about the potential implications of involving police authorities in their activities and, as a result, view the FBI's outreach with reservation. For example, in Germany, biohackers can be imprisoned for partaking in unregistered DIY activities for up to three years.

The FBI’s Biological Countermeasures Unit has studied the risks posed by biohacking concerning bioterrorism and has fostered strong relationships with community labs where genetic experimentation occurs.

Additionally, biohacking does not exist in a vacuum. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has jurisdiction over most biohacking products and biologics in the US. However, currently, no clear guidelines on biohacking as an individual vertical exist. Such uncertainty of jurisdiction was seen in the onset of stem cell research and can be curtailed with such policies and jurisdiction delineation now.

Biohacking is still finding its footing in Africa, South America, and Asia, with these continents hosting less than 60 DIY biolabs collectively. Due to the limited access to materials in these continents, biohacking has not been fostered as proficiently, and thus regulations have yet to govern them.

In India, the regulatory landscape is similar to that of the US. While no state regulations directly govern biohacking and biohackers, the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO) and Food Safety & Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and the Ministry of Ayush. Under the CDSCO, in collaboration with the Department of Biotechnology, some guidelines regulate the marketing and distribution of biologics such as the Guidelines On Similar Biologics: Regulatory Requirements for Marketing Authorisation in India, 2016 which outlines other relevant guidelines to oversee biological products. The CDSCO also outlines the Guidelines On Good Distribution Practices for Biological Products.

The lack of regulation in this space risks adverse effects from homemade gene therapies, environmental contamination resulting from poorly handled genetic reagents like viral vectors, and abandoning traditional treatments in favour of do-it-yourself experimental approaches.

However, in India, the scope of unethical and unsafe use and marketing of biohacking products is more dangerous due to its deep-rooted culture of non-regulated Ayurvedic medicine. Ayurveda often promises outcomes not based on rigorous clinical trials; however, due to their association with Indian culture, they are trusted as a solution to many health ailments. In recent years, this association of traditional solutions has been extended to modern biohacking, even by pioneering biohackers in India. While the state regulates Ayurvedic products under FSSAI standards, the CDSCO releases lists of World Health Organisation (WHO)-approved products by seller.

The lack of regulation in this space risks adverse effects from homemade gene therapies, environmental contamination resulting from poorly handled genetic reagents like viral vectors, and abandoning traditional treatments in favour of do-it-yourself experimental approaches. Specific risks and potential benefits of gene biohacking involving humans will depend on the context in which they are used.

Need for explicit regulation

In India, to address immediate risks and enhance responsible and ethical community participation in biohacking, the CDSCO can still develop guidelines for biohacking and genetic subsects to ensure public safety and limit the exploitation of users due to a lack of information and informed consent.

Overall, there remains a need for state regulation that explicitly monitors biohacking so that products follow standardised testing and safety requirements. Such measures will also promote research and innovation while preventing the uncontrolled dissemination of unproven biohackers. Additionally, clear labelling and accurate information about biohacking products and services are essential to protect consumers from using products with misleading, inaccurate, or dangerous proclamations.

Biohacking must be considered in genomic editing governance and alliances, or alliances must be built that oversee DIY biohacking, including gene editing and other forms of bioengineering.

Additionally, state efforts must include establishing ethical oversight boards that oversee genetic modifications on germ cells or embryos, requiring clear guidelines and oversight to prevent unintended or unethical consequences.

Internationally, biohacking must be considered in genomic editing governance and alliances, or alliances must be built that oversee DIY biohacking, including gene editing and other forms of bioengineering. Moreover, such international alliances, akin to the GA4GH, can address global ethical norms, innovation externalities, industry standards, and global challenges.

Biohacking, thus, presents a fascinating intersection of technology, biology, and human aspiration. It offers opportunities for improved health, cognitive enhancement, and increased longevity but raises significant ethical and safety concerns. Responsible and forward-thinking regulation is essential to harness the potential benefits of biohacking while mitigating potential risks surrounding public health. Striking the right balance between innovation and regulation will shape the future of human enhancement and ensure that these practices contribute positively to society.

Shravishtha Ajaykumar is Associate Fellow at the Centre for Security, Strategy and Technology at the Observer Research Foundation

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV