-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

India can pursue the trinity of efficiency, equity, and sustainability by combining socialist-era equity, liberalisation’s efficiency, and climate-era ecological sensibilities

Image Source: Getty Images

This essay, a tribute to the Indian economy on completing 78 years since its midnight tryst with independence, offers a retrospective review of the hits and misses to chart the road ahead. This is particularly important as, in the next two decades, the nation plans to navigate its path to Viksit Bharat@2047–the ambitious goal of being a developed nation by its centenary of freedom.

It is a stylised fact that India’s recent growth story is a post-1991 liberalisation phenomenon. The early decades of post-independence India unfold a far more layered narrative. In the aftermath of colonial extraction, the fledgling republic embraced the “Nehruvian Socialist” paradigm of development. The Five-Year Plans were adopted with the state assuming the central role in the commanding heights of the economy—steel, heavy industry, infrastructure, and a burgeoning public sector. The aspiration was clear: self-reliance, equitable distribution, and accelerated industrialisation. The model drew intellectual inspiration from Soviet central planning, but consciously adapted to fit India’s democratic polity and socio-economic realities.

The legacy of the earlier socialist era continues to shape development debates—particularly the balance between state-led investment, social equity, and market dynamism.

While this model succeeded in laying the foundations of basic industries, scientific institutions, and public infrastructure, it was bereft of the advantages of market forces and locked up private investments largely. Economic protectionism hedged manufacturing and agriculture from the vagaries of international trade, made them uncompetitive, and resulted in slow growth rates–famously (or notoriously) dubbed as the “Hindu rate of growth,” averaging around 3.5 percent annually for the first three decades. The inward-looking, import-substituting regime, combined with over-regulated private enterprise and minimal integration into global markets, constrained productivity and competitiveness. Poverty reduction was painfully slow, and inequality persisted despite redistributionist rhetoric.

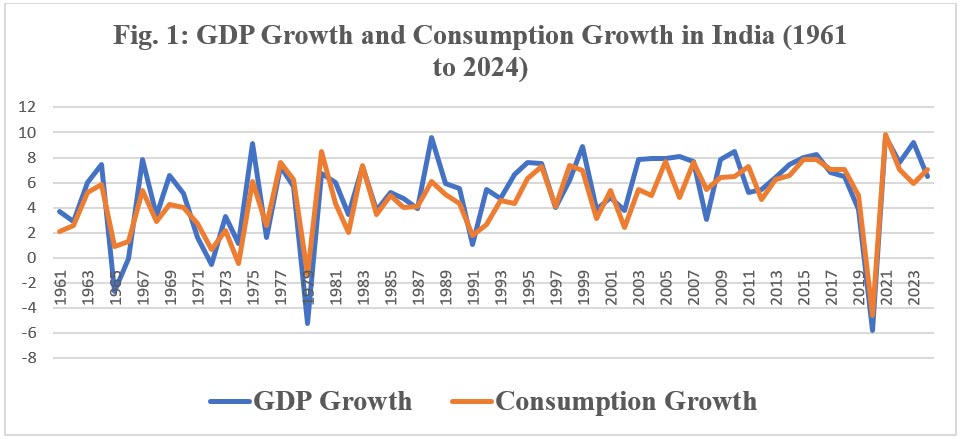

The 1991 reforms marked a paradigm shift from this insulation. The economy was opened up, industries were deregulated, and the state’s interventions shrank. The next three decades witnessed accelerated growth rates (Fig. 1), a fast decline in poverty, and the emergence of India as one of the world’s largest economies. Yet, the legacy of the earlier socialist era continues to shape development debates—particularly the balance between state-led investment, social equity, and market dynamism.

Source: World Bank Database

India’s post-reform growth trajectory is unique, with India’s expansion over the past two decades being disproportionately powered by domestic private consumption. This is in contravention of the conventional thinking that hypothesises economies transitioning from investment-led to consumption-led growth. Household spending was driven by higher disposable incomes, young demographics, and credit penetration. Consumption, thus, accounted for nearly 60 percent of GDP in recent years, higher than that of most emerging economies, and the co-movement of consumption and GDP growth became more prominent (Figure 1).

A consumption-led growth model has its advantages. It shields the economy from global demand shocks, fuels a self-reinforcing cycle between spending and production, and anchors small and medium enterprises in local markets. But sustaining such growth demands broad-based prosperity. When income and wealth skew too sharply towards the top, consumption momentum falters—the rich save more, while the poor spend nearly all they earn. India’s falling consumption Gini—from 0.288 in 2011 to 0.255 in 2022—and the sharp drop in extreme poverty from 27.1 percent to 5.3 percent are encouraging. Yet, a rising income Gini, from 0.59 to 0.61, as per the World Inequality Database, underlines the risk of persistent disparities undermining the demand base, though such measures have been under attack due to various data and estimation problems.

An equally crucial but often ignored pillar is private household savings. Consumption may power the present, but savings finance the future. Without strengthening this pool, the country risks over-reliance on foreign capital to fund its investment ambitions. The remedy lies in deepening financial inclusion, ensuring competitive real returns, and expanding tax-advantaged savings instruments. A balanced strategy that nurtures consumption while bolstering savings will be central to building a growth model that is not just resilient to shocks, but also self-sustaining in the decades ahead.

Over-reliance on a single growth driver is risky. While consumption needs to be sustained, India must diversify towards investment-driven growth. Union Budgets in recent years have consistently raised public capital expenditure to crowd in private investment by bridging infrastructure gaps, improving logistics, and enabling scale in manufacturing and services.

Investment-led growth raises productivity, diversifies the economic base, and generates quality employment. However, physical capital expansion in India and the developing world has also been associated with a decline in natural capital, i.e. forests, rivers, wetlands, etc. The solution to this problem lies in embedding sustainability factors in capital expansion through the Inclusive Wealth framework, which integrates physical, human, and natural capital into development planning.

There is empirical evidence that FDI and private investment are increasing functions of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that inherently address all four forms of capital—human, physical, natural, and social, much like the Inclusive Wealth framework. With stronger achievements in the SDGs being a signal to investors about a competitive business environment, high-performing SDG economies have attracted global value chains, green investors, and responsible capital flows.

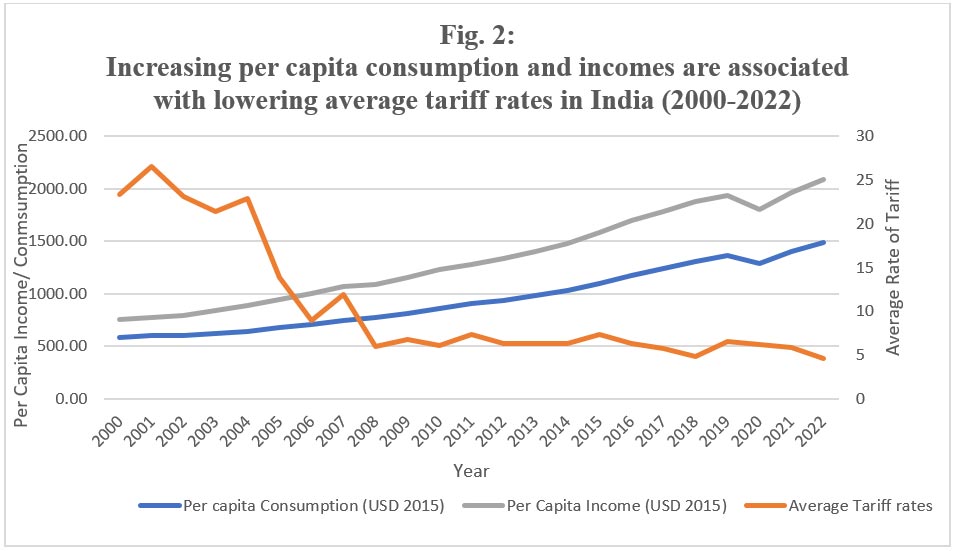

Another lever for investment and efficiency gains lies in greater global trade integration. Tariff liberalisation has historically been one of the key factors promoting India’s consumption-driven growth by lowering prices and expanding choice. Among all the major economies in the developed and developing world, India revealed the maximum percentage point decline in tariff rates during 2000-2022. Again, India’s tariff liberalisation helped the process of India’s consumption-led growth, with econometric causality being noticed (also see Figure 2).

India’s proportional contribution to global value chains (GVCs) remains negligible, particularly in high-value segments. This can be reversed by boosting productive efficiency through better CAPEX, upskilling in emerging domains such as artificial intelligence, and strengthening logistics.

Source: Prepared by the author from various sources

To achieve this, India should decisively conclude free trade agreements (FTAs) with major partners such as the European Union and fully operationalise the Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) with Australia. Such pacts not only open new markets but also anchor domestic reform by aligning standards, regulations, and production capabilities with global best practices. By all means, trade and tariff liberalisation will be good for India.

A resilient economy needs diversity in growth drivers. In India’s case, this means developing export-led sectors, expanding investment-driven manufacturing, nurturing high-productivity agriculture, and scaling up green industries—alongside sustaining domestic consumption. Strategic focus on technology-driven sectors, renewable energy, modern logistics, and high-value services such as fintech and healthtech can create new growth frontiers. In turn, these sectors can absorb skilled labour, stimulate innovation, and raise India’s share in global trade beyond its current low levels.

Viksit Bharat@2047 is more than a GDP per capita target. It must also embody equity through distributive justice, robust social security, and universal access to basic services, and sustainability through climate action and natural capital preservation. Growth without equity risks social unrest; growth without sustainability risks ecological collapse. This can be corrected with the Inclusive Wealth approach to ensure that development does not erode the very foundations of long-term prosperity.

Climate resilience is a central pillar of this vision. PM Modi’s call for LiFE (Lifestyle for Environment) at the COP26 provides a basis for ecologically aligning our development philosophy. India is among the most climate-vulnerable nations, and adaptation finance—currently the missing link—must be scaled up. Mobilising such finance requires creating measurable markets for adaptation outcomes, leveraging CSR, and philanthropic funds, and structuring public–private partnerships that share both risks and rewards.

Viksit Bharat@2047 is more than a GDP per capita target. It must also embody equity through distributive justice, robust social security, and universal access to basic services, and sustainability through climate action and natural capital preservation.

In parallel, social security systems need strengthening to provide a safety net for those adversely affected by structural transformations, automation, or climate shocks. Universal health coverage, pension schemes, and unemployment protection can ensure that the fruits of growth are more evenly shared.

From the Nehruvian state-led socialist planning to the market-oriented reforms of the 1990s, and to the sustainability-infused investment thrust of the 2020s, India’s development journey reflects a continuous evolution of priorities. The challenge is not to choose between growth drivers, but to integrate them through an integrated paradigm resting on:

By anchoring the development philosophy in Inclusive Wealth, Viksit Bharat@2047 will not be just richer, but more resilient, inclusive, and ecologically secure.

The Irreconcilable Trinity of development—efficiency, equity, and sustainability—can be pursued if only India’s adaptive pragmatism retains the equity orientation of the socialist phase, the efficiency gains of the liberalisation era, and the ecological sensibilities demanded by the climate crisis. Trade and investment promotion need to proceed hand in hand with social security reforms and climate action. By anchoring the development philosophy in Inclusive Wealth, Viksit Bharat@2047 will not be just richer, but more resilient, inclusive, and ecologically secure. The nation, freed at midnight, cannot drift during the day!

Nilanjan Ghosh is Vice President - Development Studies at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Dr Nilanjan Ghosh heads Development Studies at the Observer Research Foundation (ORF) and is the operational head of ORF’s Kolkata Centre. His career spans over ...

Read More +