Over the years of India being a democratic republic, several policies for healthcare service delivery have been introduced and implemented all across the country. However, political parties have incessantly condemned and criticised the promises of their rivals and the healthcare services have not been immune to this. Beyond the political rhetoric, it becomes imperative to examine Prime Minister’s big ticket healthcare initiative — Ayushman Bharat Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (AB-PMJAY) with respect to its feasibility and sustainability.

The programme has two pillars, one of them being Health Wellness Centres (HWC). Under this pillar, creation of 1,50,000 HWCs is under process by transforming existing sub centres and Primary health centres — covering a population of 3,000-5,000 to ensure universal access to an expanded range of comprehensive primary healthcare services. AB-PMJAY, the second pillar has been termed as one of the largest government funded healthcare programmes in the world. Although, the scheme targets more than 50 crore beneficiaries and intends to provide insurance coverage for secondary and tertiary hospitalisation to underprivileged households across the country, it has come under scrutiny on multiple avenues for not being an all-inclusive and warrantable health scheme.

An independent study carried out by the Institute of Economic Growth raises concerns about the sustainability of the scheme. As the per capita hospitalisation rates are rapidly increasing, the future premium costs to avail PMJAY could be over Rs 2,400 per family as compared to Rs 1,100 currently. By this standard, it can be assumed that in the duration of the next five years, close to 75% of the annual health budget will be put towards this scheme, leaving only a meagre amount to be invested in other major health programmes.

By 25 February 2019, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Jharkhand and Bihar had already made significant gains by providing over 10,958,358 e-cards where as the highest numbers of hospital admissions were recorded in Chhattisgarh, Kerala, Gujarat and Tamil Nadu. As on 18 June 2019, 29,16,020 beneficiaries have been admitted and over 3,74,35,078 e-cards have been issued.

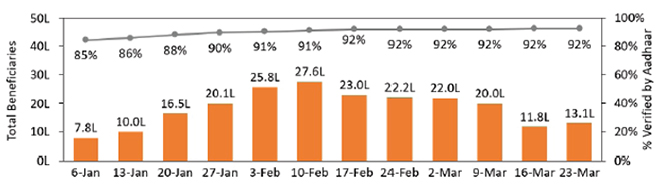

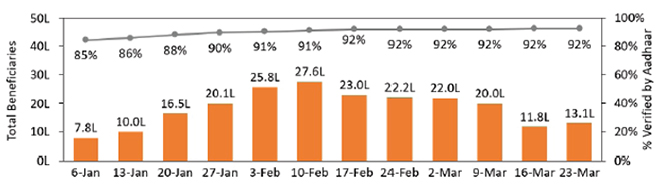

Beneficiary identification in the month of March:

Source: www.pmjay.gov.in

Source: www.pmjay.gov.in

Despite the scheme being claimed as a moderate success so far, multiple states have refused to implement it and have in fact withdrawn after the initial months, which raises serious questions about the scheme’s acceptance across India with regards to the high rates of health insurance premiums, technology absorption in uniting the stakeholders, and addressing the jurisdictional issues.

Delhi government alleges that Ayushman Bharat tries to climb up the ladder without laying the foundation and covering the bases of primary healthcare. Based on that rationale the Delhi government plans on strengthening the existing structures such as the mohalla clinics, polyclinics and specialised hospitals. It also aims to provide healthcare services at the citizens doorstep.

Much like Delhi, the states of Telangana and Odisha have prioritised their own state government schemes of Arogyasri and Biju Swasthya Kalyan Yojana respectively. Regardless of the popularity of the scheme, states such as Punjab and Chhattisgarh have heavily questioned the means of its implementation and have expressed reservations about the funding ratios put forth by the Centre. Experts argue that the states with underdeveloped public health systems such as Jharkhand stands to suffer more by implementing PMJAY due to the lack of regulation in its healthcare industries, the relative lack of private health providers in non-urban areas and the levels of development in each state compared to others.

Arguing from the point of preventive health spending, Chhattisgarh government plans on adapting an alternative scheme which covers maximum population of the state with outpatients’ care and expenditure on medicines and prefers to return to their previous system of medicine purchase, ASHA worker network and primary healthcare centres.

What needs to be seen is that states such as Kerala, Punjab, Tamil Nadu were still maintaining a high rank on the NITI Health Index before the onset of the scheme, so the question arises that what new addition does Ayushman Bharat bring to the table? Moreover, when a high performing state within PMJAY like Chhattisgarh retracts from the scheme, what does it mean for the objectives it set out to achieve?

According to the CEO of PMJAY, there seem to be two concerns regarding the scheme that can be deconstructed; i.e. Ayushman Bharat as a solution is not consistent with the problem and the resources used for the scheme should instead be spent on primary healthcare as it has been historically neglected. In order to address these concerns it is important that we also shed some light on the false perceptions being aired — that all health needs, relates to primary healthcare and there is no need to expand support towards tertiary care and that the scheme is taking money away from primary healthcare and is benefitting private hospitals.

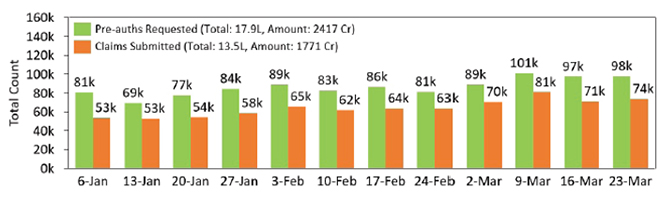

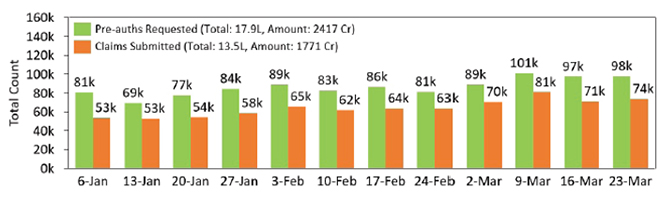

Pre-authorisation requests and claims submitted in the month of March:

Source: www.pmjay.gov.in

Source: www.pmjay.gov.in

Primary and secondary healthcare complement each other. Because of significant prevalence of non-communicable diseases and increased life-expectancy, it becomes vital to strengthen the tertiary and secondary healthcare services which are mostly provided by the private sector and makes them more accessible to the poorer population. Under the scheme so far — procedures that are more surgical in nature like, angioplasty, valve replacement/repair, coronary artery bypass graft, joint replacement among others have been the most sought after. Ayushman Bharat has proven to be a fundamental tool in bridging this previously existing gap with its two-pronged programme of PMJAY and Health and wellness centres.

There needs to be a clear-cut emphasis on the fact that there is no trade-off between primary care and curative care and this policy maybe an answer to the challenge of strengthening them both. The momentum the scheme has gained in a short time since its launch bears witness to the country's enormous unmet need for curative care and its continuation may be a giant leap in the direction of Universal Health Coverage. However, the PMJAY utilisation data is emerging slowly and there is an urgent need for it to be made public more readily in the interest of transparency and accountability.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source:

Source:  Source:

Source:  PREV

PREV