-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

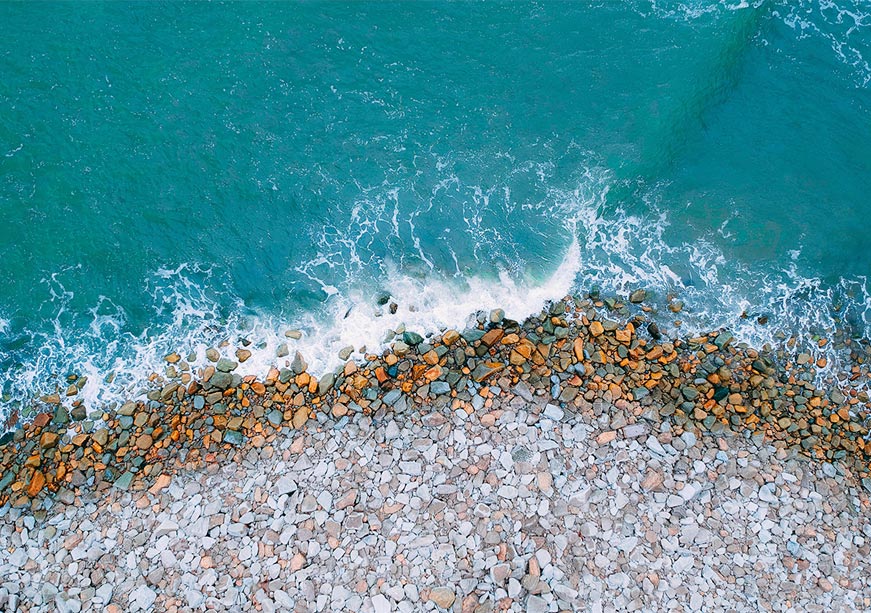

As climate change intensifies risks along the world’s coastlines, inclusive approaches to water governance and the blue economy are essential for building resilient coastal cities that safeguard both livelihoods and ecosystems.

Image Source: Pexels

This article is a part of the essay series: World Water Week 2025

Across the world’s coastlines, cities have long grown in close connection with water. Harbours, estuaries, rivers, and seas have shaped patterns of settlement, livelihoods, infrastructure, and trade. Today, coastal cities continue to serve as key hubs of the global economy, closely connected to water-based systems such as shipping, fisheries, tourism, and energy. Yet, the very waters that have sustained these cities now present a complex set of challenges and risks, especially in the context of climate change.

For urban policymakers, planners, and communities, the intersection of urbanisation, water, and the blue economy demands urgent attention. Rising sea levels, saltwater intrusion, flooding, and water scarcity directly affect urban populations and infrastructure. At the same time, the evolving notion of the blue economy — involving economic activities related to oceans, seas, and coasts — offers opportunities for resilience, sustainability, and inclusive development, provided it is approached with care towards social and ecological systems.

Water in coastal cities is not only an issue of supply and infrastructure but is fundamentally tied to questions of access, governance, and justice.

From this perspective, it is important to foreground how these challenges and opportunities play out unevenly across different populations within coastal cities. Urbanisation often produces spatial and social inequalities: informal settlements, for instance, are frequently located in vulnerable low-lying or marginal coastal zones. These communities typically have the weakest access to basic services, including safe water and sanitation, and the least influence over decision-making processes that shape urban futures.

Water in coastal cities is not only an issue of supply and infrastructure but is fundamentally tied to questions of access, governance, and justice. Many coastal cities face dual pressures: the risk of too little water due to salinisation of groundwater, drought, or over-extraction, and the threat of too much water through storm surges, flooding, or sea-level rise. These dynamics disproportionately impact lower-income groups who rely on fragile water infrastructure or informal water markets.

Moreover, the physical interface between land and sea – the beaches, wetlands, estuaries, and mangroves – plays a crucial role in both water management and livelihoods. These ecosystems support water quality, mitigate flooding, and provide the basis for small-scale fisheries, aquaculture, and tourism. Yet, urban expansion often encroaches on these spaces, degrading natural protections and limiting access for traditional user groups.

An inclusive blue economy must therefore take into account the complex, place-specific relationships between people, water, and urban space.

For instance, in Jakarta, rapid urban development and land reclamation projects have severely impacted natural wetlands and mangroves, contributing both to worsening urban floods and the erosion of livelihoods for coastal fishing communities. Similarly, in Chennai, efforts to expand infrastructure along the city's coasts have at times conflicted with the water-dependent livelihoods of artisanal fishers, while saltwater intrusion increasingly threatens groundwater reserves that supply marginalised urban neighbourhoods.

Climate adaptation strategies in coastal cities increasingly focus on water management through infrastructure such as sea walls, desalination plants, and drainage improvements. While necessary, these interventions can unintentionally reinforce exclusion if they displace communities, neglect local knowledge, or prioritise commercial interests over everyday needs. An inclusive blue economy must therefore take into account the complex, place-specific relationships between people, water, and urban space.

Global conversations on the blue economy frequently focus on sectors like maritime transport, offshore energy, or marine biotechnology. However, for many urban residents, especially in the Global South, the blue economy is experienced more directly through small-scale, everyday interactions with water-dependent systems: fisheries, water-based transport, tourism services, or informal markets. Ensuring these groups are not sidelined in policy frameworks is essential.

Inclusive blue economy policies should integrate principles of equity, participation, and local benefit. This involves recognising the rights and contributions of coastal communities within urban areas to water stewardship and blue economy activities. It also requires supporting infrastructure and governance that protect water access for vulnerable populations while enabling sustainable economic opportunities.

Examples of this approach include initiatives that connect urban water resilience with livelihoods, such as participatory wetland restoration in Manila, and municipal programmes in Mombasa that integrate informal fish markets into urban planning. In Dar es Salaam, for instance, city authorities have worked with local fishing communities to improve access to waterfront landing sites while protecting mangrove ecosystems, recognising the dual importance of livelihoods and urban resilience. Likewise, in Cartagena, Colombia, urban planning efforts have begun to incorporate the needs of small-scale fishers and coastal vendors into waterfront redevelopment projects, ensuring that these communities are not displaced by tourism or commercial expansion.

In Mumbai, India, the traditional fishing villages known as Koliwadas are increasingly being recognised in urban planning processes as critical to the city's heritage, livelihoods, and coastal ecosystem stewardship. These communities have advocated for secure tenure, access to clean and navigable waterfronts, and protection against encroachment by commercial real estate or infrastructure projects. Their inclusion in discussions around coastal zoning and blue economy strategies highlights the need to balance urban development with the rights of traditional water-dependent communities. These efforts highlight that sustainable water management and inclusive economic growth are not separate goals but deeply interconnected.

In the context of climate action, water governance in coastal cities must move beyond technical fixes to embrace inclusive processes. Governance should not only be about institutions but also about relationships between people, spaces, and resources. Inclusive governance mechanisms, whether through participatory planning, co-management of resources, or rights-based approaches, can ensure that diverse urban voices shape how water is managed and how blue economy opportunities are distributed.

Urban policies must embed strong social and environmental safeguards. Development strategies should actively account for the interdependencies between land, water, and livelihoods.

The way forward is to establish multi-level governance frameworks that align urban planning with coastal and marine priorities. This involves creating platforms for dialogue between city authorities, coastal communities, and marine stakeholders. Examples from global initiatives such as the UN Ocean Conference, the Global Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction, Sagarmanthan: The Great Oceans Dialogue, and the Resilient Cities Network demonstrate the value of cross-sector engagement in shaping sustainable coastal urban development.

Moreover, urban policies must embed strong social and environmental safeguards. Development strategies should actively account for the interdependencies between land, water, and livelihoods. Strengthening local institutions, fostering collaboration across sectors, and prioritising place-based solutions will be critical. These measures can help close gaps effectively and equitably. Some of these efforts should include the following action points:

Safeguarding water as a source of well-being is essential to creating resilient and equitable urban futures in the face of a changing climate.

The intersection of coastal urbanisation, water governance, and the blue economy presents both significant challenges and important opportunities for inclusive climate action. The future of coastal cities will be shaped not only by technological and financial solutions, but by approaches that recognise and respect diverse relationships with water, livelihoods, and urban space. Safeguarding water as a source of well-being is essential to creating resilient and equitable urban futures in the face of a changing climate.

Anusha Kesarkar Gavankar is a Senior Fellow with the Centre for Economy and Growth at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Dr. Anusha Kesarkar Gavankar is a Senior Fellow at ORF’s Centre for Economy and Growth. Her research spans urban transformation, spatial planning, habitats, and the ...

Read More +