The global North-South abyss

The COVID-19 pandemic has not only exposed the surging gaps in resource endowments within and across nations to deal with the crisis, but also the skewed macroeconomic and developmental impacts of the same. To be sure, income inequality within developed nations has been exacerbated by the pandemic where the top 1 percent has witnessed large amounts of windfall earnings over the last two years. While unemployment in the United States (US) rose by 15 percent between April and June of 2020, the five richest Americans (Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates, Warren Buffet, Mark Zuckerburg, and Larry Ellison) saw a 26-percent rise in wealth during the same period. Their combined wealth is now higher than the total combined wealth of the entire African continent.

Again, divergences in developmental parameters between the global North and South have become extremely apparent too. Education is one such example—children in advanced economies lost an average of 15 days of school in 2020 due to the pandemic. The number rose to 45 in the case of emerging-market economies, and 72 for children in the poorest nations. The impact on income, similarly, was far higher in developing nations. A higher reliance on the informal sector in the poorer economies meant that when lockdowns and other restrictions started becoming the norm, unemployment and poverty continued to rise due to the collapse of market forces that maintained certain macroeconomic equilibria.

Although governments in the developing world have tried to ease the burden on the poor through social security schemes and benefits that were intended to subsume the lacunae created by the collapse of the economy, they pale in comparison to those available in developed economies. Eligible adult citizens in the US received a minimum of US$ 1,200 as stimulus checks, while government efforts in developing countries were insufficient due to higher fiscal deficits, and would often not reach the intended beneficiaries due to inherent corruption.

A higher reliance on the informal sector in the poorer economies meant that when lockdowns and other restrictions started becoming the norm, unemployment and poverty continued to rise due to the collapse of market forces that maintained certain macroeconomic equilibria.

On the other hand, the technology required immediate attention to accumulate the growing demand as education and offices shifted online. The need to build better virtual networks between government agencies and other organisations has never been stronger. Though this benefited nations as a whole, it perpetuated the rich-poor divide in the poorer nations such as those in South and Southeast Asia and Africa, where the affluent classes will be the only ones who will continue with seamless access to these privileges in the future. However, developed and developing economies where technology is abundant and accessible are not plagued by such inequalities, at least not to the extent of underdeveloped economies.

Implications for sustainable development

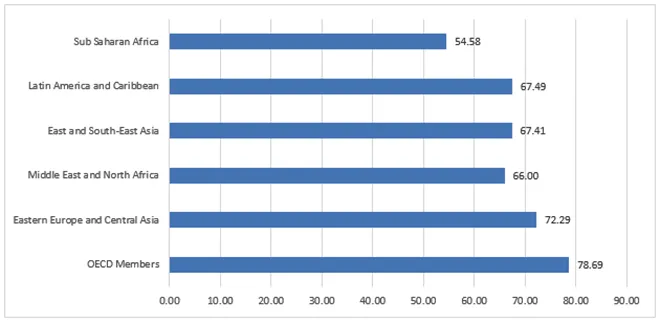

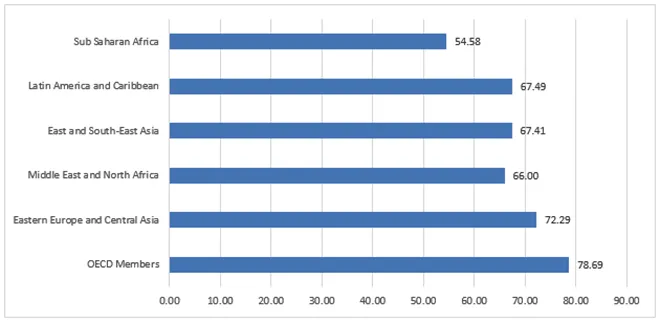

Against this background, it is quite prominent that the world economies are transitioning towards multipolar convergence clubs between the developed and the developing worlds. Simultaneously, the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) which have been envisioned as a global push to ensure that the world moves towards an equitable, peaceful, and prosperous future intend to tackle the sustainable development challenge through the combined lens of society, economy, and environment. Though the SDGs envisage such change to be brought about around the world, the disparities between the global North and South in their respective abilities to achieve the same, loom large. Undoubtedly, the pandemic has had a detrimental impact on the manifestation of these trends.

Figure 1: SDG Scores 2022 by Groupings (out of 100)

Source: Sachs et al., 2022

Source: Sachs et al., 2022

Firstly, there are inherent trade-offs within the SDG framework where one goal may have positive or negative impacts on others. For example, SDG 9 (industry, innovation, and infrastructure) will always have an inherent tendency to have negative externalities on SDG 13 (climate action). The complex network of interlinkages between the sustainable development objectives makes it impossible for the whole framework to function if one or more targets fall apart due to various direct and indirect consequences of the pandemic. The vulnerability of these developmental objectives is much higher in poorer nations, making them more susceptible to the trail of failures in terms of the SDGs.

Secondly, the actions of one nation can influence other nations’ ability to achieve SDGs. Such economic, environmental, and social impacts often translate into costs or losses for the recipient nations and can stall any efforts they might have made. For example, ‘green growth’ processes in the advanced economies have often laid massive footprints in the poorer nations as the former have shifted their manufacturing units to the latter. The break caused by the pandemic has accelerated the urgency to meet the SDGs by 2030; but that only increases the risk for the poorer nations in this regard. If the progress made by one nation or a group of them comes at a cost of other nations, the global community is merely engaging in a zero-sum game — which is meaningless in terms of the holistic nature of the SDGs.

Economic, environmental, and social impacts often translate into costs or losses for the recipient nations and can stall any efforts they might have made.

Thirdly, meeting the SDG targets would unquestionably need a renewed focus and ample financing from both the public and private sectors in the post-pandemic world. The lack of a robust private sector and scarce financial resources will be more challenging for the developing world than for the advanced nations. These are even worsened due to the pandemic-induced macroeconomic instabilities we see across many developing and underdeveloped nations in recent times—ranging from inflationary pressures to soaring current account deficits.

Finally, this divergence in resources available to the global North and South also includes unequal access to necessary data and underdeveloped scientific capacities, and thus acts as a major barrier to the world that is trying to achieve equitable progress. Nations with lower income levels struggle to touch the higher technological levels of developed nations from decades ago. The global shortages in resources have had skewed effects on the developed and the developing world, with the latter finding it more challenging to adapt to the same. A more proactive approach would involve the North’s efforts to inculcate the interests of the South, as mitigating such disparities is crucial in achieving SDGs by 2030.

(The author acknowledges Rohan Ross at NLSIU, Bengaluru, for his research assistance on this essay.)

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV