Anti-Indian perceptions and sentiments have been a long-standing phenomenon in South Asia. The revival of the ‘

India Out’ campaign in the Maldives in early January is a mere case in point of this continuing issue.

While

Bhutan and

Afghanistan have retained a positive perception of India due to their differences with China and Pakistan, the same isn’t true for Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and the Maldives. Many sections of people and politicians from these countries continue to perceive and portray India with animosity, lack of trust, and scepticism. It is thus vital to assess and address the root causes of these anti-Indian sentiments to shape an efficient neighbourhood strategy and policy.

This two-part article series thus aims to reason the factors that have initiated and promoted anti-Indian sentiments in the neighbourhood. The first part will examine the role of the region’s history and identity, and India’s internal and external interests. The second part will then assess the role of unresolved issues, economic relations, domestic politics, and the promotion of democracy in fostering these anti-Indian sentiments.

History and identity formation

History continues to shape South Asia’s present inter-state behaviour and attitudes. While China remains a relatively new player in the subcontinent, independent Pakistan had the opportunity to repackage and disconnect itself from Indian history and civilisation. But, on the other hand, independent India has shaped its identity and nation by mainly drawing from its civilisational history and ethnic and regional diversity.

In Bangladesh, the memories of Hindu Zamindars and the partitions of 1905 and 1947 continue to sow seeds of scepticism against India.

These diverse regions and ethnicities have had different interactions with their neighbouring kingdoms and states in the past. This has continued to shape the smaller states’ perception of an independent India. The past interactions have not always been hostile but some negative interactions and events have been reinforced as collective memories. This is largely practised by the elites and populace of these countries to preserve their uniqueness and identity ever since India emerged as an independent state.

Thus, both Sri Lanka and the Maldives still remember India from its days of the

Chola invasion. In Bangladesh, the

memories of Hindu Zamindars and the partitions of 1905 and 1947 continue to sow seeds of scepticism against India.

Similarly, being a non-colonised kingdom and having jurisdiction over Lumbini determines

Nepal’s identity vis-à-vis India. Religion has also played a vital role in this differentiation. Sections of the

Maldives and Bangladesh view independent India as a Hindu state, where Muslims are looked down on as secondary citizens. In Sri Lanka, too, India is perceived as a Hindu state

pushing back against Buddhism. This has been substantiated with India's ancient history and Tamil policy vis-à-vis Sri Lanka.

These factors of history and identity formation have thus sown the initial seeds of scepticism against the Indian state. And this phenomenon has prevailed since India’s independence.

Internal others and India’s internal security

Throughout its historic and civilisational interactions, India has had its ethnic and religious spillover with its modern-day neighbours, such as the Madhesis in Nepal, Tamils in Sri Lanka, and Hindus in Bangladesh. This has shaped a policy perception, where India’s security and peace are intertwined with an inclusive, stable, and peaceful neighbourhood.

Throughout its historic and civilisational interactions, India has had its ethnic and religious spillover with its modern-day neighbours, such as the Madhesis in Nepal, Tamils in Sri Lanka, and Hindus in Bangladesh.

But, these ethnic or religious spillovers have not always been perceived positively by others. The Tamils, the

Madhesis, and the Hindus are seen as others and outsiders by sections of elites and extremist elements in

Sri Lanka, Nepal, and

Bangladesh. Evidently, India has protested, raised concerns, or even intervened in these countries when its fellow-ethnics and religious groups are threatened.

For instance, in the 1980s, India used its coercive tactics against

Sri Lanka and also deployed its forces to end the Tamil-Sinhala conflict. It also

continues to raise the issues of the 13th amendment and reconciliation of the Tamils with Sri Lanka. In Nepal, India insisted on promoting

an inclusive democratic framework for the Madhesis and was involved in an

alleged blockade when its elites failed to do so. In Bangladesh too, India has continued to raise concerns over

majoritarian attacks against Hindu minorities.

These actions have fostered a few negative perceptions too. India's actions and complaints against its neighbours are looked down on as a big brother that intervenes in other countries sovereign affairs. Similarly, it is also perceived that India prioritises some over

the rest of its neighbours and supports political parties or elites that favour its interests. These perceptions have intensified the small states' scepticism for the Indian state.

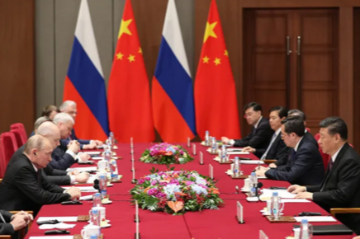

Geopolitics and strategic rivalry:

India’s strategic calculations and the increasing involvement of external players have also contributed to anti-Indian sentiments. Traditionally, India has viewed its neighbours with a

security-centric lens and has treated South Asia and the Indian Ocean as its sphere of influence and the first line of defence. It had used several incentives and coercive tactics such as

micro-management of others’ internal politics, drawing treaties, and economic blockades to maintain its status quo during the Cold War era. Although this had mitigated the threats from Pakistan and China and helped India maintain its status quo, it had created a perception of India dictating its smaller neighbours’ domestic and foreign policies.

But with China’s rise, South Asian countries are also hoping to reap economic benefits

from the former through its Belt Road Initiative (BRI) and infrastructure investments. While India has attempted to maintain its status quo by countering these projects, it has also persuaded its neighbours to respect its sensitivities and security. This has created a perception amongst some segments that India continues to involve

too much while offering too little.

While India has attempted to maintain its status quo by countering these projects, it has also persuaded its neighbours to respect its sensitivities and security.

In addition, Pakistan and China have also used some segments from the smaller countries to further anti-Indian protests and sentiments. And this is often carried forward by these segments with the hopes of ideological benefits or financial and political gains. For instance, there are strong ideological linkages between Pakistan and the Bangladesh’s Islamist parties and organisations,

such as Hefazat-e-Islam and Jamaat-e-Islami. It is even alleged that these organisations were

funded by Pakistan to conduct the anti-Modi protests in Bangladesh.

Similarly, China’s support for some leaders like Yameen in the Maldives and KP Oli in Nepal has emboldened their anti-Indian electoral base, rhetoric, and policies. Financial incentives have also likely played a role, as both

Oli and

Yameen are accused of mass corruption when dealing with Chinese firms and investments. China had even used President Yameen in the

Maldives to problematise India’s role as a net security provider. As the tensions intensified in Doklam in 2017, Yameen re-energised his anti-Indian rhetoric and narratives

by politicising the deployment of Indian patrol vessels, aircraft, and staff in the Maldives. This also explains the recent

momentum surge with the ‘India Out’ protests as soon as Yameen was acquitted.

Thus, India’s attempts to maintain the status-quo and China’s increasing role and influence in the neighbourhood will further these anti-Indian sentiments.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Anti-Indian perceptions and sentiments have been a long-standing phenomenon in South Asia. The revival of the ‘

Anti-Indian perceptions and sentiments have been a long-standing phenomenon in South Asia. The revival of the ‘ PREV

PREV